eBook - ePub

Voices of the Border

Testimonios of Migration, Deportation, and Asylum

Tobin Hansen, María Engracia Robles Robles, Tobin Hansen, María Engracia Robles Robles

This is a test

Share book

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Voices of the Border

Testimonios of Migration, Deportation, and Asylum

Tobin Hansen, María Engracia Robles Robles, Tobin Hansen, María Engracia Robles Robles

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A collection of personal narratives of migrants crossing the US-Mexico border, Voices of the Border brings us closer to this community of people and their strength, love, and courage in the face of hardship and injustice. Chapter introductions provide readers with a broader understanding of their experiences and the consequences of public policy.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Voices of the Border an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Voices of the Border by Tobin Hansen, María Engracia Robles Robles, Tobin Hansen, María Engracia Robles Robles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Política de inmigración. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Testimonios from Nogales

Tobin Hansen

Miguel recounts years of agricultural work.1 His brown eyes become glassy and his shoulders slump. Over decades Miguel has moved between Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, and the Pacific Northwest, following crops through fertile valleys, hills, and lowlands. After several years in Oregon and Washington, he returned to Oaxaca some years back to work his own small farm there. He hoped to provide a decent living for his family, be closer to them, and live a fuller life.

But in November 2017, he says while telling me his testimonio, he found himself traveling north again. The prospect did not sit well with him. But he was heading back to Oregon por necesidad, out of necessity, because in Oaxaca ya no hay trabajo, there’s no more work. The trip to Nogales—a Mexican border town an hour south of Tucson, Arizona, where he and I were talking—took three days on a cramped bus. Once here, he connected with a guide, called a guía or pollero, to lead him through an arid ecoregion of the Sonoran Desert called Altar, whose extreme temperatures make it simultaneously the hottest desert in Mexico as well as one with subzero temperatures certain times of year. Under a blackened night sky, walking on scrabble-clay earth outside the city, the cold bit his hands. His mind flashed to his kids and elderly parents. “I couldn’t keep up. I was just going up and down these rocky hills. And I fell down, like, several times. I got scared and couldn’t keep going. I started crying. The group kept going. I sat down and started crying and crying. And I asked myself, ‘What am I doing here? What am I doing so far from home?’”

Miguel felt a poignance and unease. Seemingly the last option he had—that of long hours of work in western Oregon’s lush but unforgiving vegetable and fruit farms—had disappeared. Miguel wandered under the night sky and, because he had only begun the several days’ walk northward through the desert, made his way south across an area of the US-Mexico border not even marked by a fence and east back to Nogales. Days later, talking with me, Miguel reflected on his life and speculated about his options. Was there a less arduous way to get where his labor would be valued? And if people were so eager to hire him in the United States, why is getting there to work made so difficult for people like him? How long would he be stuck in Nogales? What would come next?

This book offers historical context and draws attention to the voices of people, like Miguel, who have experienced life on the move. It illuminates the terrain that Miguel and countless others have traveled as they have migrated, sought refuge, or been deported from the United States over Mexico’s northern border. Miguel’s questions form the book’s starting point: What are people doing around the US-Mexico borderlands, in motion and in stillness? Why has the border, and places they have come from or where they are going, become a site of suffering, whether they are there for a long or short time? How has the arc of history from colonialism to the present—the evolution of nation-state power, shifting immigration laws and policies, the squeeze of global capitalism, diverse familial and financial situations, persistent faith—shaped the options available to people? These questions are vital for understanding human movement and learning more about aspects of life in the US-Mexico borderlands. And the book takes a particular structure in order to answer them. The following chapters each have a thematic focus and begin with short introductions written by migrant advocates, humanitarian aid workers, religious leaders, and scholars to explain the broad, historical contours of these themes. Each chapter then presents two or more testimonios—first-person narratives that bear witness to historical events through lived experiences—to amplify the voices of people like Miguel and document the circumstances surrounding human movement to, from, and across the US-Mexico border today.

The people at the center of this book seek positive change, and yet local and global dynamics guide their journeys along unpredictable and arduous paths. The uncertainty of their course propels sudden motion and then, just as suddenly, immobility. At one moment not another second can go by, and then, in an instant, there is no choice but to stay put and wait for days, weeks, months, or years. These abrupt changes in hopes, plans, and possibilities are not born of capriciousness. The brute facts of global markets, harsh immigration controls, and social and political conflicts deeply affect peoples’ lives and constrain their options. Despite these obstacles, people in these situations navigate their circumstances with determination and ingenuity. They want to do. To endeavor. To live.

This book focuses on those who migrate, seek asylum, or have been deported and have passed through or ended up in Nogales, Mexico. The labels “migrant,” “asylum-seeker,” and “deportee,” occasionally used in this book, are a practical shorthand and reflect processes of physical and social mobility and stasis. But the labels encapsulate only a narrow slice of the full humanity of the people featured in this book. They do little to capture the rich, infinitely complex personhood of each individual, and these categories themselves are not fixed but fluid and imprecise. Migrants find themselves on the move to reunite with family, search for work, or escape vulnerable situations. Asylum-seekers are migrants who request recognition—by the US government, in this case—of a fear of persecution in their place of nationality. Deportees have been coercively removed by the US government over the US-Mexico border. But all have unique experiences, personalities, and personal identities.

People who migrate, seek asylum, or are deported end up in Nogales, for a few hours or a few years or more, in myriad ways. Some might trek for several weeks by bus, truck, on top of a train, and on foot: from northern Honduras, over the Guatemalan border, across the Suchiate River into Mexico, and over the expanse of countryside, railroad tracks, highways, and urban centers that is Mexico.2 Others may have come as children to the United States from rural Mexico in the 1960s, ’70s, or ’80s, to live decades in Arizona or California only to later be identified by immigration enforcement officials, detained, jailed, processed, and eventually driven to the US-Mexico border in a US government–chartered bus in handcuffs and shackles, to be let out and walked over the international boundary.

People arrive in Nogales with diverse plans. Some are eager to leave. Nogales is another stop on the migrant journey to Chicago or Seattle. From Nogales, it’s a bumpy ride in a cramped van just minutes or hours westward, to stage with a group of people migrating and be guided north through deadly desert. Or Nogales is the first taste of a type of freedom for people being deported after the coercive restraint of immigration prison in the United States; the first step on Mexican soil when led over the border from southern Arizona, a place from which to catch a bus back to Piedras Negras, Veracruz, or Apango, Guerrero. People may spend an afternoon in Nogales, if that. Other people may have no bus to catch and spend a few days or a week, waiting for the right time to move on. People wait because traveling south is unsafe or people say crossing north is especially dangerous at the moment. Maybe there’s no guide available. Perhaps a body is exhausted by the journey and needs time to recover. The money could have run out. A relative might be on the way. For a minority of people who come, the weeks in Nogales stretch, becoming months and years. For deported people who have lived many years in the United States, there is no home anywhere else. Or upon arriving at the doorstep of the United States, fleeing violence elsewhere in the world, people seek the chance merely to plead with a US official for an asylum hearing. If an asylum claimant is not deemed to express a “credible fear,” then it’s back to Mexico or Honduras or Brazil or Haiti. And what then? Back home, in the communities from which people fled, life is too perilous. But if people make it back to northern Mexico, having already been denied asylum in the United States, a clandestine desert crossing into southern Arizona in search of safety is too potentially fatal. Nogales is a place full of people who have burst into motion and then stood still, whose plans may change or remain constant. They are people looking for a way forward.

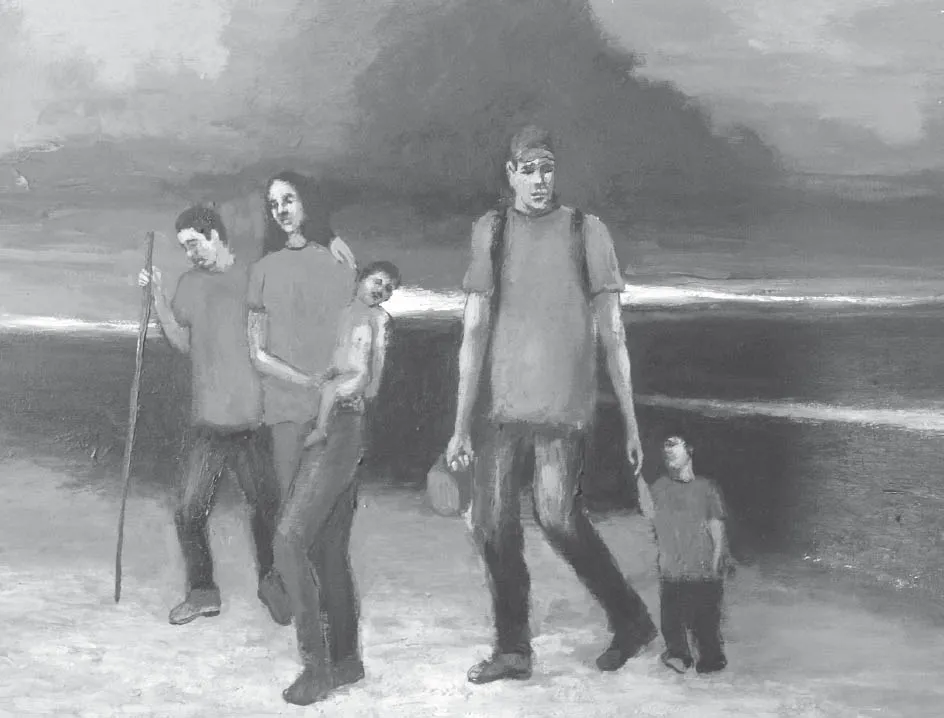

Migrants trek northward through the desert. Wenceslao Hernández Hernández.

Miguel’s perspectives, and those of others on the move, matter. They give insight into the lives they lead, choices they make, options available, and day-to-day experiences. Although some politicians, media commentators, and others in the United States fixate on immigration, the strength of their beliefs and opinions is outsized given that their knowledge of mobile people’s lives and the structures that shape them is frequently scarce. Some vocal pundits, public officials, and everyday people herald border “crises,” mischaracterize and demonize immigration, and speculate about who people are and how they live with little grasp of the situation on the ground or historical context. Others have firsthand knowledge, as community members who live near or visit the border, or have become involved as migrant advocates. Still others have become informed by the growing historical record compiled by the solid reporting of dedicated journalists and the insightful research of social scientists. For those who wish to learn more, this book permits insight of a particular kind: it takes the midsized city of Nogales, Mexico, as a hub of diverse forms of movement and stasis about which less is known than the metropolitan areas of Ciudad Juárez, Matamoros, Nuevo Laredo, Reynosa, and Tijuana. Moreover, we reproduce testimonios to elevate voices of those who have come to Nogales, usually passing through, to shed light on the emotional, psychological, embodied, and experiential aspects of life stuck in place or on the move. The act of testifying and of documenting testimonios also enriches historical narratives surrounding contested aspects of life.3 According to anthropologist Lynn Stephen, writing about the importance of testimony in the context of truth commissions, “oral testimony has become a vehicle for broadening historical truth by opening up the range of who can legitimately speak and be heard and, ultimately, who participates in the construction of shared social memory.”4 Giving, recording, reproducing, and listening to or reading testimonios, then, are acts of legitimation, of history-making and of broadening spaces wherein marginalized people become seen as authentic, proper, and warranted participants in history as well as makers of history. The voices of people on the move in and around Nogales matter not only for the unique point of view that they provide, but because people on the move matter as full participants in communities, nations, and in an interconnected world.

The book emerged as a collaboration between people seeking to draw attention to testimonios. Those of us who have collaborated are all deeply and personally attached—via professional, vocational, religious, or humanitarian commitments—to the Kino Border Initiative (KBI), a migration advocacy organization. Kino is based in Nogales, Mexico, in the Mexican state of Sonora, and its sister city, also called Nogales, that adjoins the US-Mexico border on the north, in Arizona. Kino runs several programs in Mexico and the United States. It provides direct services to migrants, deportees, and refugees; advocates on behalf of humane migration policy; collaborates with scholars to advance research; and educates youth and adult populations alike on migration-related issues. Our collaboration grew from the vision to create an educational resource for those who seek to understand stories like Miguel’s, as well as the cycles of migration, deportation, and political asylum; the public policies and social and economic circumstances that invigorate or disrupt these cycles; and the consequences of these dynamics. It also emerged through the connection to Nogales that each of us, writers of introductions or sharers of testimonios, has come to establish as we also have come into contact with the city.

People stand outside the Kino Border Initiative comedor. April Wong.

NOGALES IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, grew historically through human movement and settlement and abuts what today is one of the longest and most regulated international borders in the world. Nogales has a population of about 234,000 located in a basin-and-range area of the Sonoran Desert, where the Santa Cruz River snakes northward. The landscape is a crumpled napkin. Hills, ravines, and desert washes cut from volcanic rock over millions of years reach an altitude of 3,480 feet above sea level and, atop sheer ridges, some 5,610 feet.5 Average high temperatures in July, despite the mitigating altitude, reach ninety-two degrees Fahrenheit while in January lows average thirty-six degrees and frequently dip below freezing. Enormous factories line the southern edge, residential neighborhoods dot the expanse of the city, and, where the border fence juts horizontally across its northern edge, souvenir shops sell Mexican handicraft kitsch and no-frills eateries cater to tourists strolling into Mexico from Arizona.

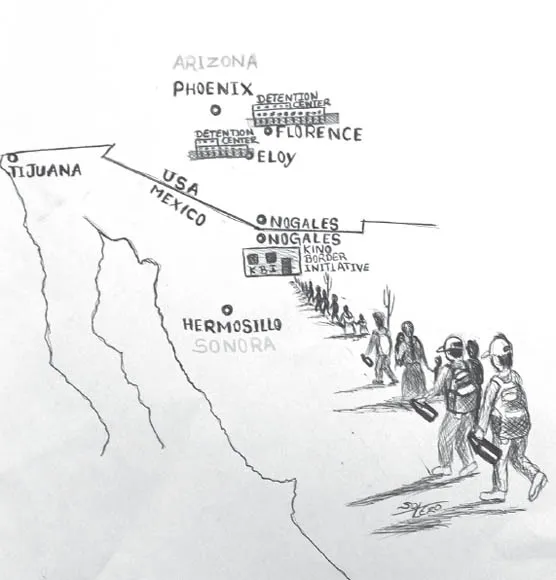

Map of Arizona-Sonora borderlands region. José Luis Cabrera Sotero.

Mountains in the Sonoran Desert. Avery Ellfeldt.

A few centuries ago, this sparsely populated, twisting series of ridges and gullies comprised Spanish territory. A trail traversing the area provided a critical connection between New Spain’s northernmost settlement, Tucson, some sixty miles north, and points south.6 Apaches, Opatas, Pimas, Tohono O’odam, and Yaquis lived and moved in this area where mestizos—people of combined European and Indigenous descent—and so-called Anglos also occasionally passed on horseback through the hard clay terrain of prickly pear cactus, mesquite trees, ocotillo, co...