eBook - ePub

The Hidden Mathematics of Sport

Rob Eastaway, John Haigh

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Hidden Mathematics of Sport

Rob Eastaway, John Haigh

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This fascinating book explores the mathematics involved in all your favourite sports.

The Hidden Mathematics of Sport takes a unique and fascinating look at sport by exploring the mathematics behind the action. You'll discover the best tactics for taking a penalty, the pros and cons of being a consistent golfer, the surprising connection between American football and cricket, the quirky history of league tables, the unusual location of England's earliest 'football' matches and how to avoid marathon tennis matches. Whatever your sporting interests, from boxing to figure skating, from rugby to horse racing, you will find plenty to absorb and amuse you in this insightful book.

Word count: 35, 000 words

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Hidden Mathematics of Sport an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Hidden Mathematics of Sport by Rob Eastaway, John Haigh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mathématiques & Jeux en mathématiques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MathématiquesSubtopic

Jeux en mathématiquesCHAPTER 1

HOW TO WIN MORE GOLD MEDALS

And how many medals your country might expect

Ethelbert Talbot is not a name that naturally trips off the tongue when it comes to great sporting quotations. It was he, however, who in 1908 delivered a sermon at St Paul’s Cathedral that included what was to become an immortal line:

The important thing in these Olympic Games is not so much winning as taking part.

Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics, heard the sermon and adapted this line to become the creed for the movement. It’s a creed that sits comfortably with the general public, but not necessarily with the media or with government, who deep down know that from their point of view, it’s not so much the taking part that is important, but the tally of medals.

For years, the greatest battle to top the medals table was between the USA and the former Soviet Union. For the remainder of the twenty-first century, it may well become China versus the Rest of the World. But it’s not just the big countries that want medals. The tiny island nations cherish the achievement of a single bronze just as much. The question is: are there tactics that a country can use in order to get more medals? And when does the athlete of modest abilities have the best chance of getting onto the podium? In the eyes of the world looking at the medals table, all golds are equal. But to misquote George Orwell, some golds are more equal than others.

Jessica Ennis-Hill, Olympic Gold medallist and World Champion heptathlete.

The benefits of size

Money is one obvious route to winning more gold medals. There is a good correlation between the wealth of a country and the number of medals that it wins. There are two reasons for this. Countries with a high Gross Domestic Product (GDP) tend to have a large population, and the greater the number of people, the more likely it is that a star athlete is among them. But wealth also brings with it the luxury of being able to invest in sports amenities, and big countries like to make their presence felt too, so it becomes politically important to register on the medals table.

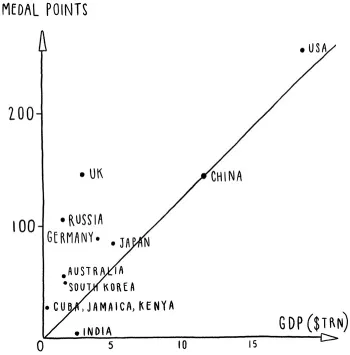

Calculating the medal points for the 2016 Rio Olympics using the traditional method of three points for gold, two for silver and one for bronze leads to a scatter chart of medal points against GDP. Many countries do seem to fit quite closely to the line that we have somewhat arbitrarily drawn through zero and through China’s point on the chart. Those countries that are above the dotted line have performed better than the link would suggest, while those below have performed worse.

The diagram above highlights some notable exceptions, namely those countries well away from the line. Of the leading countries, the UK performed exceptionally well, even better than when London hosted the Games in 2012. Kenya, Jamaica and Cuba showed their traditional strengths in distance running, sprints and boxing, and Russia does well, having a low GDP for its large population. Australia’s passion for sport is such that its place on this chart does no more than nod at its expectations.

South Korea is not normally seen as a sporting nation – in athletics, its last medal was in 1996 – but it consistently ranks high in these tables, because of its strength in archery, judo and taekwondo. (And in the Winter Olympics, look out for South Korean speed skaters.) Japan won 41 medals in Rio, just two of them in athletics, but they were prominent in gymnastics, wrestling and judo.

On the other axis, the country that stands out is India. Despite a population of over a billion people, India obtained just one Silver and one Bronze in 2016. Part of the explanation is down to the country’s overwhelming passion for cricket, a sport that hasn’t appeared in the Olympics since 1900. That’s another rule for getting medals: make sure you concentrate on sports that actually feature in the tournament.

Why big countries win team sports

There is another, more subtle reason why large countries might be favoured when it comes to winning medals. Many medals are for teams, rather than individuals. This doesn’t just mean the traditional team sports like hockey and basketball, but sports where individual performances are added together, such as gymnastics, and the relay races in athletics and swimming.

Team sports favour big countries. You can just about imagine a Liechtenstein runner winning the 400 metres, but you can’t imagine that country winning the 4 x 400 metres relay. In fact there is a mathematical reason why team sports favour big countries disproportionately.

In sports for individuals, it would seem reasonable to expect the chance that the winner comes from a particular country is simply proportional to that country’s size, all things being equal. But the number of ways of choosing two people, for sports like doubles in tennis or badminton, depends on the square of the population size. So if one country has three times the population of another, its winning chance here should be three-squared or nine times as large. With larger teams, such as the teams of four for a relay, the relative strength of a ‘wealthier’ country gets even higher. The moral of this argument is that smaller, poorer countries should invest in individuals, leaving the team sports to richer nations.

Reducing the competition

There’s another simple principle for improving your chances of winning gold, and it is connected to money. Keep the number of competitors down to a minimum. The fewer rivals you have, the better your chances of winning.

One of the best ways of excluding other competitors is by pricing them out of the market. So for a country in search of gold, the Marathon is unlikely to be fertile ground, the problem being that everyone can take part. On the other hand, if the sport in question needs, say, an expensive yacht, then many countries are excluded simply on cost grounds, and others are excluded because they are landlocked. We don’t expect a Nepalese yachtsman to be standing on the podium collecting a medal any time soon.

Sometimes, intrepid teams can achieve remarkable things despite the lack of amenities – the feats of Jamaica’s bobsleigh teams in several winter Olympics being a glorious example. But these are the exception.

Other sports requiring extremely pricey equipment include cycling, rowing and (if you can call a horse ‘equipment’) show jumping. Competitors in these sports rightly point out that the competition for medals is still extremely fierce, but the entry-level costs mean that a huge proportion of the world’s population is effectively excluded from taking part.

Multiple golds versus all-round winners

There are also some sports where an individual has the opportunity to win several medals using the same basic skill – in swimming for example. So the cynical country looking to improve its medal count might hit the jackpot by concentrating on exclusive sports where a number of medals are available.

In several sports, there have been competitors who achieved success in more than one event. Kelly Holmes, Jesse Owens and Emil Zatopek all won golds in different athletics events, but these pale in comparison with the swimmers. The greatest feat used to be considered as that of Mark Spitz, who won seven gold medals in 1972. But Michael Phelps won 28 medals, 23 of them Gold, between 2004 and 2016, eclipsing Soviet gymnast Larissa Latynina’s 18 medals (9 Gold) from 1956 to 1964.

Nobody will dispute that to win one gold is a great achievement, and that to win two or more is remarkable. Yet there is something unsatisfactory about the fact that multiple golds are almost always won in disciplines where there are several similar contests, but over different distances.

After all, if a swimmer can win the 100 metres freestyle by a clear margin, it’s not altogether surprising that they can win the 200 metres and even the 50 metres. Take the argument to an extreme: we could see a 100 metres race, a 120 metres race and so on, and award a gold medal in each. The same couple of swimmers would likely share all the golds between them, adding massively to their countries’ tally.

In contrast, multi-discipline events are almost worthy of more than one medal. It seems rather unfair that the men and women who win the decathlon and the heptathlon get only one gold medal each. These competitions are spread over two days, and are widely regarded as the best tests of who is the leading all-round athlete.

If they are to be fair tests, then the best sprinter should be no more and no less likely to win than the best jumper or the best thrower. When, for example, fibreglass came into use, dramatically increasing the heights jumped in the pole vault, the scoring system was soon adjusted to bring the specialist vaulters back into line.

In practice, proficiency in some events often goes with proficiency in others – top sprinters are often successful long jumpers, and good discus throwers can usually put the shot well. To achieve fairness, it doesn’t really matter if one of the events consistently tends to score even 100 points more than the rest, as all competitors get the same benefit. But it is important that the variability of the scores across the events is similar. If one event tends to display much more variability than the rest, then the specialists in that event will be favoured. The reason is that those who are best in that event will score more extra points (above the event’s typical score) than those who are best in events that show less variation.

A study of five decathlon world championships reached clear conclusions. Except for the 1500 metres, the variability of performance within the field events was rather more than in the track events.

The 1500 metres is always the last event, and by the time it starts, most competitors will know that they are well out of the medals. This reduced incentive to press to the limit might partly explain why the performances in it are so variable. So if we set aside this last event, it looks as though the decathlon set-up favours the throwers rather than the runners.

This same study confirmed what you might expect. Athletes achieving high scores on the shorter track events tended to score highly on the long jump; and the scores for the three throwing events were strongly linked. But there were also some surprises: good throwers tended to be good pole vaulters, while the best high jumpers were often strong in the 1500 metres.

If you had to use performance in just one of the ten events to predict the winner of the decathlon, which would you plump for? You are looking for an event with ‘transferable skills’, and the answer might change if the scoring system changed. But at the moment, the answer is the long jump, just ahead of the discus throw. So if any decathlon coach is scouting for talent, they might hang around the long jump pit, and take the best jumpers for a try-out with the discus. It’s no coincidence that Britain’s best ever decathlete, Daley Thompson, was a long-jumper first.

Puzzle – Sports Segregation

One oddity about Olympic sports is the sometimes arbitrary way that some sports segregate competitors into categories while others don’t. You can be of (relatively) slight stature and still win gold as a weigh...