![]()

PART ONE

Language and Mysticism

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

On the Meaning and Relation of Absolute and Relative (1950)

DO YOU EVER WONDER?

How interesting would it be to be able to read the thoughts of others? There they are, walking down the street or sitting idly in a train or bus, and their eyes tell little or nothing of what is going on inside their heads. What do they think about? What schemes, what puzzles, what dreams, what mysteries, are they turning over in their minds? It might not be interesting at all, for it is possible that, whether working or idling, so many of these people are not interested, and who is not interested is not interesting. Their minds may just be turning over the most humdrum little worries, or odds and ends of gossip, or merely futile fantasies. In this case, the power to read thoughts would be a dubious gift—the mastery of a language with an exceedingly dreary literature.

But surely there must be times when the thoughts of the dullest person are wonderful. Of course, we use the word “wonderful” in two senses: “I have just had a wonderful time,” or “This is a most wonderful universe.” In the first sense, “wonderful” is just an exaggeration for pleasant or amusing. In the second, it means what it says—full of wonder, of fascination, mystery, and interest. Yet the two senses are not always separate, because a life that has been spent in wondering will almost certainly have been a wonderful life. Most children seem to be having an interesting time, for the world is a new thing in their eyes, and they are always asking questions. The more one asks, and gets answers to, questions, the more are the questions to be asked, for the more we know, the more we know we don’t know. The size of the mystery always grows in proportion to the increase of knowledge. Discovery is always, to some extent, the finding of new things about which you are ignorant.

A person who has given up asking questions, who has ceased to wonder, has stopped living because he has stopped growing. For life is like a stream in the sense that it must flow on or cease to be a stream. And where the mind of man ceases to flow out in wonder and interest towards the ocean of reality that surrounds him, it turns back upon itself and becomes a stagnant pool. A person who is miserable or bored is one whose mind has turned back upon itself, a person who gets in the way of his own experience, who frets over how he feels and how he would like to feel, and yet always seems to feel the same—frustrated. Yet all this turning back, this self-concern, is like a snake trying to make a good meal off his own tail—a futile procedure that makes him gag, and that boils down to the ultimate absurdity of trying to feed on one’s own hunger.

Obviously, then, life is interesting and wonderful to the extent that one has interest in it and wonder for it. It is superficially wonderful if you wonder only at superficial things, and deeply wonderful if you wonder at deep things. To wonder what Mrs. Smith will wear for the party, what would have happened if you had been the son of a millionaire, what the dentist will have to say about your teeth, or whether it will be a fine weekend, is to wonder only at surfaces. It seems astonishing that there can be minds that never go deeper, that never want to know who or what is the mysterious power of consciousness that looks out through Mrs. Smith’s eyes, how it is that I am myself and not someone else, why it is that I love pleasure and hate pain, or how there comes to be a sun that can shine.

It is difficult to imagine many questions more interesting than these. Yet the asking and answering of them is a process called philosophy, which is popularly thought to be one of the drier subjects in a college curriculum as well as one of the most unprofitable professions. If such things are dry and dull, life is then dry and dull at its very core, and one must just as well commit suicide without further ado. This is, perhaps, what our world is doing. Its daily life must be such a round of inane tedium that it can think of nothing better to do with the marvels of atomic fission than make a sensational bang, and blow itself up.

Needless to say, philosophy is not just another course in college, or the wearing out of one’s mind with volumes of incomprehensible verbiage. Philosophy, as Aristotle said, begins and ends in wonder—wonder at what lies beneath the surface, not only of the sun, moon, and stars, but also of the most trivial and commonplace events. Every child is born a philosopher. Not only does he take things apart to find out how they work, but also he asks the most profound questions as to who made God, whether space goes on forever, what happened before anything happened, whether he would have been born if Mother had married someone else, why this, why that, why anything and everything. It is tragic that this spontaneous venture of wonder and interest in the roots of life bogs down either in parental annoyance, or in university courses where gentlemen expert in chopping logic dismiss all such questions as meaningless.

In a very strict sense it may be meaningless to ask why there is a universe, or whether I might have been someone else than me. But if the human mind had never wondered at these things, there would have been no physics, no chemistry, no biology or astronomy. Perhaps a question that has no answer is a meaningless question, but we can never find this out until we are sure it has no answer. And the good scientist is never quite sure, being the least dogmatic of people.

For many hundreds of years the scientific mind has been trying to find out what things are—what stones and stars and men are made of. Reducing them to simpler elements, it wants to know, in turn, what these are made of. Finding that men and mountains and air are arrangements of such simpler things as carbon, oxygen, sulfur, and hydrogen, and that these are composed of molecules, and these of atoms, and these of electrons, protons, and neutrons, we begin to wonder how much further we can go, how much longer we can ask, “What is it made of?” For we have brought everything down to such a fine point, that the investigation is now rather like trying to stick the point of a needle into the point of a needle. If the mind of man is of the same substance as the universe that it investigates, must there not come a time when the whole inquiry is just a single substance trying to define itself—like a mouth trying to kiss itself or a flame to burn itself?

At present there does seem to be a tendency among scientists to feel that this “main line” of inquiry has reached its limits, as if the mind had reached an impenetrable wall, and must henceforth be content to explore its surface. In a remarkable passage in The Evolution of Physics Einstein and Infeld (1938) say:

In our endeavor to understand reality we are somewhat like a man trying to understand the mechanism of a closed watch. He sees the face and the moving hands, even hears its ticking, but he has no way of opening the case. If he is ingenious he may form some picture of a mechanism which could be responsible for all the things he observes, but he may never be quite sure his picture is the only one which could explain his observations. He will never be able to compare his picture with the real mechanism and he cannot even imagine the possibility or the meaning of such a comparison. (p. 38)

Back at the end of the nineteenth century, Maxwell foresaw the same problem, and explained it with an illustration employing a cabinet instead of a watch. Imagine a cabinet whose doors are forever sealed, but in each door there is a minute hole from which there extends a string. When we pull string A, string B goes up, and conversely. The scientist can but note the regularity of this event. As to what goes on inside the cabinet—whether A and B are two ends of one string, or whether there is some more complex mechanism—he can only speculate; he can never know for certain.

If physics cannot penetrate the watch or the cabinet, or if its method of inquiry has reduced itself to a needle trying to prick the point of a needle, must the whole problem be brought to a close? Must it be said that any further questioning as to what reality is, is meaningless? One may say so, and yet the human mind will go on wondering, because unsatisfied with the answer. The problem is simply whether it is entirely useless and absurd to do so.

The very analogy employed by Einstein and Infeld (1938) suggests an answer. Strictly speaking, the function of science may be simply to observe, measure, and predict the movements of the watch’s hands and the rhythm of its ticking. Beyond this point, no observation is possible, and no measurement. But in fact, the scientist does form theories of what lies inside the watch, and tests them by the degree to which they enable him to predict what the watch will do. In this respect science enters the realm of philosophy and metaphysics, which is the act of wondering about the inside of the watch or the cabinet, about the depths of reality that are beyond the experience of the senses.

The philosopher forms and tests his theories in somewhat the same way as the scientist. He develops an idea of what may be inside the watch and responsible for its external movements from things that he has seen outside the watch. Outside, he has observed the things that make movements and noises similar to those of the watch, as well as the processes that cause them. He then reasons that the movements and noises of the watch must have similar causes, assuming that the relation of cause and effect that exists outside must also exist inside.

To these theories he applies a test not unlike the scientist’s test of prediction. He asks whether his theories enable man to make a better adaptation to the world. If they do so, he assumes that his theory is in harmony with, or corresponds to, the unknown reality that causes this world. But this is not all. The problem of adaptation to the future course of events is not the philosopher’s only or even chief concern. For he realizes that it is of no use to be able to predict and adjust oneself to the future unless you are also capable of having harmony with life in the present. Lacking this, you are always preparing for a tomorrow that never comes. You predict, but do not fully enjoy the fruits of prediction and planning when they become present.

Therefore the philosopher also loves philosophy for itself. He finds that wondering is perhaps the highest form of enjoyment, because in this act he loses himself in the contemplation of the most fascinating of all things—the reality that lies beyond the senses. All enjoyment, all real happiness involves this loss of self-consciousness through absorption in something wonderful. Can there, then, be any other higher happiness than absorption in the “highest” mystery—the unseen reality that underlies this whole universe? In the words of Goethe, “The highest to which man can attain is wonder; and if the prime phenomenon makes him wonder, let him be content; nothing higher can it give him, and nothing further should he seek for behind it; here is the limit.”

OUR INCOMPLETE MAP OF LIFE

We come, then, to the barrier that the scientists say they cannot pass unless they join hands with the philosophers and begin to speculate and wonder. This wondering is no useless reaching into the void, and no mere attempt to satisfy curiosity. The correct solution to many of the problems of living in this everyday world depend upon accurate reasoning about the world beyond the senses. For this other world is in no way remote from the world of practical life; it is really the same world, understood more deeply. It is as if we were traveling across a sheet of ice. The senses can see, as it were, only the surface, and other means must be used to discover where the ice is thick enough to carry our weight, and so to decide what course the journey must take.

We must be prepared, however, for reasoning about the unseen to lead us to some strange conclusions. Already the scientists have found that their own theories of “the world below the surface” are very hard to describe in concrete images. They speak of space being curved, and how can we imagine space with a curve in it, as if it were the film of a soap-bubble without, however, either an inside or an outside? While we shall always use concrete images for purposes of illustration, it must nevertheless be remembered that these are only images, and that what we are talking about is not exactly like them. A familiar example of this difficulty may be seen in trying to draw a cube on a flat surface.

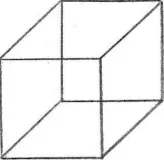

To represent a cube on this flat sheet of paper, we draw two squares, and then join their corners with straight lines (see figure 1.1). But this figure is not a cube. For all the angles of a cube are right angles, but in this drawing many of them are not. Yet because we know what a real cube is, we can imagine one from this drawing by using the convention of perspective. Because we are familiar with a world of three dimensions, we can easily understand representations of this solid world upon a flat surface where there are only two dimensions.

Figure 1.1. A Necker Cube representing a three-dimensional perspective.

Supposing, however, there were people living in a world of two dimensions, people who had never seen, and had no idea of a third. They would find it most difficult to understand this drawing. A line perpendicular to their world would seem to them like a point, a surface like a line, and a solid like a surface. They would see the drawing here only as two squares with triangles adjoining them. Thus we are somewhat like these inhabitants of “Flatland” in our attempts to understand the world beyond our senses. Indeed, it took many centuries for our own ancestors to understand how this earth could be spherical, because to their limited point of view it seemed so flat. How could anyone walk on the underside of such a globe without falling off?

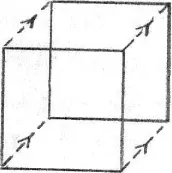

It is easy enough to see how the inhabitants of “Flatland” could not understand our drawing of a cube. It is fairly easy to put ourselves in their position by doing something else to our drawing. Here is the square. Think of it as made by moving the upright line at the left (one dimension) over to the right (two dimensions) (see figure 1.2). Here we have the two dimensions of length and breadth. Now by moving the whole square through the third dimension of depth, we have once more the cube (see figure 1.3). So far the figure is quite understandable. But now let us suppose that there is still another dimension, at right angles to each one of the three. We move the whole cube through this dimension, and get what is called a tesseract (see figure 1.4).

Figure 1.2. A square representing a two-dimensional perspective.

Figure 1.3. A Necker Cube representing acquisition of a three-dime...