![]()

1

Mennonites, Mormons, and the Registration of Foreigners in the 1930s and 1940s

A Rare Attempt to Promote Integration

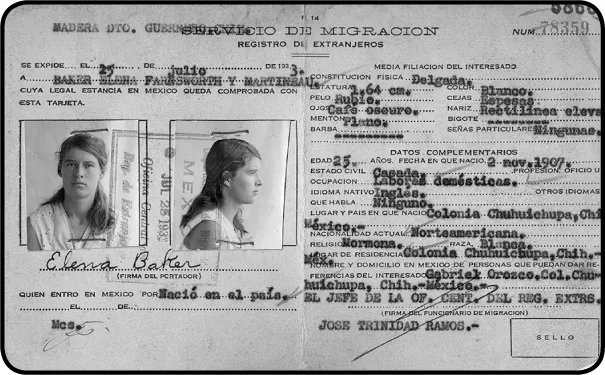

Figure 1 Elena Farnsworth y Martineau Baker. Image courtesy of the Archivo General de la Nación, Fondo “Departamento de Migración, Subserie estadounidenses.”

ELENA FARNSWORTH Y MARTINEAU BAKER

This image, representing one of the members of these minority communities, is from an interaction with bureaucrats representing the majority community. It is taken from a 1933 Mexican migration document and portrays Elena Farnsworth y Martineau Baker, a young American woman of the Mormon religion. It consists of her photograph and basic information about her, as recorded by a Mexican official. In the photograph, she stares at the camera in a way that suggests her determination, and her expressionless mouth indicates that she has been photographed before and that she, like most people, is not interested in a bureaucratic photo. The way her long hair is pulled away from her face in a low half-ponytail and the fact that she wears a sleeveless top, with a high V-neck, gives her a somewhat stylish appearance. Her card says that she is twenty-five years old, married, and engaged in domestic labor. The official has described her “physical constitution” as thin, though she looks quite average. The official may describe her this way because that is what he expected for a young woman from the US. Her official reference, Gabriel Orozco, reflects the fact that the Mormons had some contact and interaction with the surrounding community. Indeed, Mormons had some Spanish-speaking people in their churches at that time. In spite of this apparent contact with the outside world, the card says that Elena speaks English and no other languages. This means that she does not speak Spanish, though her name is written in a way that suggests Hispanicization. That she was born in Mexico, in the Mormon colony, but was still required to register implies that legally, she continued to be a foreigner.

This card is one of thousands that the Mexican government required of resident foreigners from 1926 to 1951 (H. Herrera, Informe 1). According to Mexico’s Archivo General de la Nación [National Archive] approximately 40,000 of these cards are for Americans. Of these, a modest number are for Mormons. About 4,000 cards are for Canadians and most of these are for Mennonites. Others are for people from various places, including the Middle East, Europe, and Asia. When I, while in Mexico’s Archivo General in 2015 researching other matters, happened to come upon these cards my first thought was, might there be cards for my relatives? Thanks to a kind archivist, I soon found myself looking at the cards of my great-grandmother and several great-uncles and aunts who were part of the small Mennonite migration from Canada to Mexico in 1948, well after the larger migration of the 1920s.

I then wanted to learn more about this registration. Literature on the history of Mormons and Mennonites in Mexico did not deal much with them. Literature on the Mormons did not mention the registration at all and that on the Mennonites had only a few small references to it. Theresa Alfaro-Velcamp in her excellent So Far From Allah, So Close to Mexico: Middle Eastern Immigrants in Modern Mexico (2007) refers to the registration a number of times but does not say what its purpose was or how the registration was carried out. My search in the archives was not fruitful on these points either. There is a line on each card acknowledging the right of the registrant to reside in Mexico, but that right is not granted by this card; it already existed. Bruce Wiebe, who had worked with Mennonite Archives in Manitoba, Canada, informed me that in 1989 the archivist in Mexico City, Juan Manuel Herrera H, had written to the Mennonite Heritage Centre in Winnipeg about the Mennonite cards, believing that they might be of interest to Canadian Mennonite researchers. Reportedly, after staff at the Heritage Centre had expressed interest, Mr. Herrera had sent them information about 4,000 such cards made for Mennonites. But he had provided little by way of explanation. As a result, the cards and the registration process remain largely unexamined.

The registration represented a significant encounter between the post-Revolutionary government and the recently arrive Mennonites and the Mormons returning home. The Mennonites and the Mormons, both of whom had had negative experiences with the governments where they had lived before, were apprehensive about this government’s intent: was this registration requirement a sign that it would also take steps against their way of life. For its part, the Mexican government had broad policy objectives to which this registration was to contribute. For this reason, they were interested in people’s race, color, and appearance. This allowed the officials making the cards to categorize the people from these groups. In some cases, their written descriptions are different from what is obvious in the photographs, and some of the people present themselves in ways quite unusual for their communities at that time. This chapter sheds light on these and related questions.

The registration of foreigners was one element in the post-Revolutionary government’s overall intent to promote the integration of the various kinds of people living in its territory. In the first part of this chapter, I explore the integration project, and in the second part I look at a sample of the registration cards in light of that intent and in light of certain cultural aspects, showing both similarities and differences. Close examination of that integrationist intent and of the work of gathering the information, that is, registering the people to yield a fuller understanding of Mexico, and of these groups, in that era.

THE REGISTRATION IN THE CONTEXT OF THE GOVERNMENT’S NATION-BUILDING POLICIES

At a basic level, the post-Revolutionary government wanted to assert control over its territory, given that fighting from 1910 to 1920 had almost “reduced Mexico to a patchwork of warring factions” (Knight “Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo” 84). They may have worried that these groups would rise up again with the help of resident foreigners. Indeed, there were coup attempts in 1924 and 1927. And from 1926 to 1929, there was the Cristero War in which many Catholics, supported by the church hierarchy, fought against the government because of its anticlerical measures. In addition there was concern about people with close connections to the US and possible incursions they might provoke. Also, in the half century before the revolution, a large number of foreigners from many different countries had moved to Mexico, some with little documentation, given that passports with photographs had not yet become a standard requirement. A registration would at least give the new government some solid information about how many foreigners there were, where they had come from, where they were living in Mexico, and what they were doing there.

Control over the territory was merely one element in the government’s agenda of nation-building. That agenda also meant building a common identity and loyalty among the country’s disparate groups. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Spanish colonizers’ locally born descendants, known as criollos, attempted to remain separate from the various indigenous groups. Gradually, the number of people who identified as mestizo, or mixed race, grew, though the criollos held most of the power. In the mid-nineteenth century there were legal reforms toward an equality of citizenship but the tripartite schema of white, mestizo, and Mexico’s indigenous would form the basis of the country’s censuses later that century (Stern “Eugenics” 156). In the later years of the nineteenth century, in a push toward development and modernization, the government worked to attract immigrants. It passed the Colonization and Naturalization Act (1883) to encourage foreigners to settle sparsely populated areas (Pegler-Gordon 16, 28). Also, it sought investors, particularly from Europe, to counterbalance those from the US, to help develop mines, build transportation and electricity infrastructure, expand agricultural production, and increase exports (Alfaro-Velcamp 183). These modernizing changes, however, dispossessed many peasants so there was resentment, as is evident in the then-popular saying: “Mexico, mother of foreigners and stepmother of Mexicans” (Alfaro-Velcamp 158).

Despite antiforeigner sentiment, Alfaro-Velcamp observes that Mexican policy makers continued to welcome immigrants, particularly Europeans, “who were perceived to potentially ‘better’ the nation with skills and capital—and in some cases fair skin” (Alfaro-Velcamp). Justo Sierra, Minister of Public Education and Fine Arts from 1905 to 1911, said: “We need to attract immigrants from Europe so as to obtain a cross with the indigenous race, for only European blood can keep the level of civilization … from sinking which would mean regression, not evolution” (Knight “Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo” 78). The reference to “a cross with the indigenous race” points to the mestizo idea on which the post-Revolutionary government would try to build a national identity. Already in 1909, before the revolution, Molina Enriquez stated: “all the work that in future will be undertaken for the good of the country must be the continuation of the mestizos as the dominant ethnic element” (qtd. in Knight “Racism, Revolution, and Indigenismo” 85). Alfaro-Velcamp adds that the mestizo idea “represented a way … to create a liberal model of homogenous integration of all ethnic groups. By encouraging individual groups—specifically indigenous peoples—to shed their distinctive characteristics and to become mestizo, they could become part of an evolving Mexican nation” (Alfaro-Velcamp 17). In Europe and the US, it was held that hybrids were “inherently degenerate” but in Mexico the mestizo idea provided “an appealing and invigorating vision of racial amalgamation that resonated well with the ideals of (post) revolutionary nationalism” (Stern “Eugenics” 161). José Vasconcelos, the post-Revolutionary Secretary of Public Education, articulated a vision for the mestizo idea with particular eloquence. In a long 1925 essay called The Cosmic Race he compared the Mexican situation to what he called the Anglo-Saxons, claiming:

It seems as if God Himself guided the steps of the Anglo-Saxon cause, while we kill each other on account of dogma … They do not … have … in their blood the contradictory instincts of a mixture of dissimilar races, but they committed the sin of destroying those races, while we assimilated them, and this gives us new rights and hopes for a mission without precedent in History. … The advantage of our tradition is that it has a greater facility of sympathy towards strangers. This implies that our civilization, with all defects, may be the chosen one to assimilate and to transform mankind into a new type; that within our civilization, the warp, the multiple and rich plasma of future humanity is thus prepared. This mandate from History is first noticed in that abundance of love that allowed the Spaniard to create a new race with the Indian and the Black, profusely spreading white ancestry … Spanish colonization created mixed races, this signals its character, fixes its responsibility, and defines its future. (17)

Thus, the mestizo idea had particular implications for foreigners and for the indigenous people, as if both were to move toward a middle ground. Stern adds that Vasconcelos envisioned the mestizo as a “spiritual beacon of Hispanic civilization,” which rejected European scientific doctrines of race, derived from Darwin and Comte, which had the effect of seeing the mestizo as inferior (“Mestizophilia” 191). Alfaro-Velcamp sheds further light on this situation: “the mestizo construction aimed to temper the influence of foreigners and the visibility of the indigenous, thereby limiting plurality” (italics in text, 19). This construction of the mestizo idea was helped by the creation, in 1929, of Partido Mexicano Revolucionario [Mexican Revolutionary Party] (PRM), which would become the Partido Revolucionario Institucional [Institutional Revolutionary Party] (PRI). The PRI then ruled Mexico continuously for the next seventy-one years and it employed Vasconcelos’ language as “a type of ‘meta-discourse’ … to explain national identity …” (Alfaro-Velcamp 19). Alfaro-Velcamp continues:

The post-revolutionary construction of the mestizo was in large part based on the ideas of intellectuals … who suggested that the lack of ethnic integration was at the root of many of Mexico’s problems. They advocated a type of unity—arguably homogeneity—to integrate the divided Mexico … [thus] limiting ethnocultural plurality and allowing for hegemonic discourse. (italics in text, 159)

The registration of foreigners was related to this broad effort to build a national identity on the basis of the mestizo idea. The registration would be a way of assessing the foreigners’ racial characteristics so as to take them into account in the overall effort to build this new identity. Hence the questions on the cards about race, color, eyes, nose, general appearance, and constitution. The questions about face shape relate to ideas about phrenology, the science of cranial shape. It was believed that certain physical features were more criminal than others; the Mexican government thus sought to avoid criminals whenever possible.

The Mennonites and Mormons remained separate and distinct. This suggests that integration was incomplete. Alfaro-Velcamp concurs, holding that most foreigners did not begin to identify as mestizo, that they retained much of their own heritages while also developing significant roles in Mexican society, and that the Mexican people usually accepted that. Nor, in the first decades of the twentieth century, was there a major movement of indigenous people to become mestizo (Knight 98; Stern “Eugenics” 164). Alfaro-Velcamp concludes: “Despite the intellectuals’ attempts to construct a monolithic Mexico, the Mexican populace … developed into a pluralistic society that allowed many ways of being Mexican” (Alfaro-Velcamp 159). She says that Mexico in fact developed a “rich cultural mosaic” (Alfaro-Velcamp 19).

The overall goals of integration and assimilation may not have been achieved; however, the registration of foreigners was, nevertheless, undertaken as one element in the pursuit of these goals. I look at the broader efforts that the government made to achieve those goals in order to better situate the registration of foreigners as an element in them. To do this, it is helpful to acknowledge the work in Mexico on eugenics, an idea that was supported in many countries in the half-century before World War II, though now universally rejected because of its connection to the racial horrors of the Nazis (Stern “Eugenics” 152). Narrowly understood, eugenics called for the biological improvement of a population, for example, by preventing so-called unfit people from having children (Stern “Eugenics” 165). Thus, for some decades in parts of the US and Canada people with mental illnesses were forcibly sterilized; and for people to get married they first had to pass a medical test; also, in many states in the US, mixed race marriages were outlawed because any children born of such parents were believed to be inherently degenerate (Stern “Eugenics” 160, 171). In the US, the Race Betterment Foundation was set up in 1906 by John Harvey Kellogg. On immigration, wealthier and better-educated Americans, particularly those whose ancestors had come from English-speaking or northern European countries, were concerned about “impoverished hordes of swarthy newcomers from the ostensibly less civilized European countries of Poland, Russia and Italy … [bringing] a massive influx of defective ‘germ plasm’ … [thus] threatening to contaminate and destroy America’s superior racial stock” (Stern “Eugenics” 166). One result of this sentiment was the 1924 National Origins Act that restricted the immigration of people from southern and eastern Europe and banned Asians and Arabs completely (Stern “Eugenics” 167).

The idea of eugenics also enjoyed support in Mexico but with substantial differences. Instead of being focused on keeping an existing race pure, the intent in Mexico was on building a new mestizo race, and there was a certain confidence that eventually the various groups would all blend into a mestizo nation (Stern “Eugenics” 159). This implied a firm rejection of the view that children of mixed race parents were degenerate. Further, Mexican intellectuals and policy makers held to the Lamarckian theory about “the inheritance of acquired characteristics” first advocated by Jean Baptiste de Lamarck, a French biologist, in the early 1800s (Stern “Mestizophilia” 190). This theory, which was also accepted in France, Italy, and some other Latin American countries, was different from the Mendelian theory, commonly held in the US and Germany, which claimed that “hereditary material was transmitted … with absolutely no alteration” (Stern “Mestizophilia” 190). The Lamarckian view “flourished in Mexico because it implied that human actors were capable, albeit gradually, of improving the national ‘stock’ through environmental intervention and, eventually, of generating a robust populace” (Stern “Mestizophilia” 190). In effect, this me...