![]()

Part I Dispatches from the First America

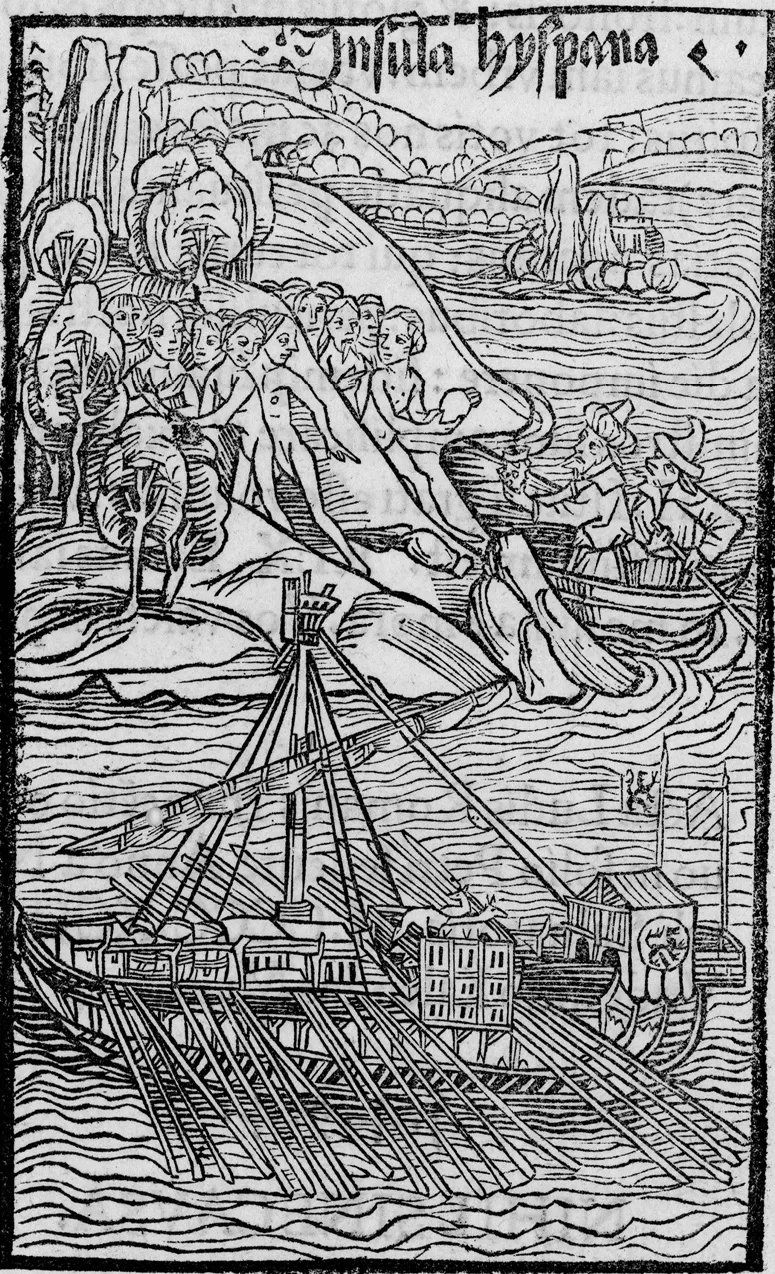

A woodcut illustration from the 1494 publication of Christopher Columbus’s report of his arrival in the New World.

![]()

Chapter 1 HEAVEN AND HELL

The history of Cuba begins where American history begins. History, of course, has more than one meaning. It refers to events of the past—war and peace, scientific breakthroughs and mass migrations, the collapse of a civilization, the liberation of a people. But history also refers to the stories that people tell about those pasts. History in the first sense refers to what happened; in the second, to what is said to have happened. Cuban history begins as American history does in the second sense of the word: history as narrative, as one telling of many possible ones, invariably grander and necessarily smaller than the other kind of history—history as it is lived.1

For both Cuba and the United States, this second kind of history—history-as-narrative—often begins in 1492 with the epic miscalculation of a Genoese navigator Americans know as Christopher Columbus. In its day, Columbus’s gaffe was a perfectly reasonable one. He had studied navigational maps and treatises of both his contemporaries and the ancients; he had sailed on Portuguese ships to Iceland and West Africa. He understood—as had the Greeks and Muslims long before and most Europeans in his own time—that the world was not flat. And he used that knowledge and experience to make a deceptively simple argument. From Europe, the best way to reach the East was to sail west.

In an age when every European explorer was racing to find new trade routes to Asia, Columbus approached several European monarchs to propose his westerly route. The king of Portugal said no. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain twice rejected the proposal. Eventually, after his third attempt, they decided to let him try. The year was 1492. The Spanish monarchs had just waged the final, victorious campaign of the Christian Reconquest, ending seven hundred years of Muslim control on the Iberian Peninsula. The majestic city of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold, fell to the Catholic kings on January 2, 1492. Columbus was there that day. He saw the royal banners of Ferdinand and Isabella flying atop the towers of the Alhambra, and he watched as the Muslim king knelt to kiss their royal hands. Columbus was still in the city later that month when Ferdinand and Isabella ordered Jewish residents of their kingdoms to convert to Christianity, leave voluntarily, or face expulsion. Thus did Columbus witness the final victory of a militant and intolerant religiosity. In fact, he was its beneficiary, for it was only with that war over that the Catholic monarchs acceded to Columbus’s unusual venture.

On Friday, August 3, 1492, just three days after the deadline for the Jews of Spain to leave and a half hour before sunrise, Columbus set sail. He bore the title the king and queen had conferred on him: High Admiral of the Ocean Sea and Viceroy and Governor for life of all the islands and continents he might discover. As befitting a man of that rank, he peered out at the horizon with confidence. Wealthy, thriving Asia awaited him, just on the other side of a sea he was sure he could cross “in a few days with a fair wind.”2

Two months and nine days later, on October 12, 1492, Columbus and his weary sailors made landfall on a small island. Convinced he was somewhere in Asia, which Europeans of the time called India, he asked two captains to “bear faithful testimony that he, in the presence of all, had taken… possession of the said island for the King and for the Queen his Lords.”3 Columbus directed a secretary to come ashore with him and consign the event to writing, and therefore to history. Nothing anyone wrote, not even Columbus’s own journal, survived in its original form. The people who watched from shore—henceforth known to Europeans as Indians because of Columbus’s error—wrote nothing at all. Even had the first survived and the second existed, no writing produced in that moment could have conveyed the momentousness those events would later acquire. Columbus and his men had arrived in another world—new to them, ancient to the people already there. With that arrival began not history itself, but one of the most important chapters of it ever written.

THE STORY OF COLUMBUS’S ARRIVAL in the so-called New World is completely familiar to readers in the United States and has been for centuries. One of the country’s early national anthems was called “Hail, Columbia,” the title referring, of course, to Columbus. Cities and towns across the young country took Columbus’s name. In the nation’s capital, the District of Columbia, a painting called the Landing of Columbus has graced the Rotunda of the Capitol Building since the 1850s. The date of that landing remains today a national holiday. Generations of American schoolchildren have learned the story of Columbus, usually only a little after learning to read. That they often forget most of the details can be gleaned from the recent experience of a park ranger at the national monument at Plymouth Rock, the site of the first landing of the Mayflower pilgrims. The park ranger once explained that the most common questions she fields from visitors have to do with the famous Genoese sailor. “Was this where Columbus first landed?” they often ask her. Confused, many ask why the historical marker at the site says 1620 and not 1492.4 Columbus begins US history not only in this kind of popular conception, but also in much of the nation’s written history, from the very first ones ever published in the early decades of the nineteenth century to the 2018 book These Truths: A History of the United States, by Harvard professor and New Yorker writer Jill Lepore.5

For decades, historians and activists have pointed out at least two glaring problems with the Columbus myth as history. They focus on the violence unleashed by Columbus’s arrival—the long and tragic history of genocide and Native dispossession it inaugurated. Here, Columbus is no hero at all. In 2020, activists across the United States targeted monuments dedicated to his memory—tying ropes around his statue and pulling it down in Minneapolis, beheading one in Boston, setting another aflame in Richmond and then plunging it into a lake. Activists and historians point out another simple fact: namely, that Columbus did not discover America. The people of the lands on which he arrived in 1492 already knew they were there. The hemisphere had a population significantly larger than Europe’s and cities that rivaled Europe’s in size. Its people had political systems, agriculture, science, their own sense of history, their own origin stories set in pasts long before Columbus. This critical and accurate appraisal of the Columbus myth applies not just to the United States, but to Cuba and all the Americas.

Yet there is a further distortion that arises from making Columbus the beginning of US history specifically. In a casual conversation with a Connecticut businessman waiting to board a flight in Havana’s airport, I mentioned writing a book on the history of Cuba from Columbus to the present. His question was sincere: Did Columbus discover Cuba, too? I hesitated before responding, feeling a little like the park ranger at Plymouth Rock. He did land in Cuba, I said, forgoing the word discover. But he never set foot anywhere on what we now call the United States. The businessman looked at me in disbelief. It was a simple, indisputable fact received like a revelation: Columbus never came to this America.

How is it that a history that did not even occur on the North American continent came to serve as the obligatory origin point of US history? There are, after all, other possibilities—even for those people who insist on beginning with the arrival of Europeans: Leif Erikson and the Vikings in 1000, for example, or John Cabot in 1497, Jamestown in 1607, or Plymouth Rock in 1620, to name the most obvious. Scholars sometimes maintain that a newly independent United States, searching for an origin story not indebted to Great Britain (its erstwhile mother country), pivoted to embrace Christopher Columbus and 1492. Then the renarration stuck.6

Yet Columbus was convenient for another reason as well. The conception of US history as originating in 1492 emerged precisely as the new country’s leaders began developing policies of territorial expansion. As early as 1786, Thomas Jefferson had prophesied that Spain’s empire would collapse, and he expressed his wish for the United States to acquire it “peice by peice [sic].”7 By the 1820s and 1830s, Jefferson’s casually stated desire had become a matter of national policy. The 1820s saw the enunciation of the Monroe Doctrine, which sought to limit the reach of Europe in newly independent Latin America, leaving the continent open to the growing power of the United States. The 1840s saw the emergence of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States was meant to extend through Indian and Spanish territories all the way to the continent’s Pacific Coast. The lands of the collapsing Spanish Empire, an empire set in motion by Columbus’s voyage of 1492, were now squarely in the sights of American leaders. George Bancroft, the author of one of the very first histories of the United States, was one of those politicians. As secretary of the navy and acting secretary of war, his actions would further US expansion into once-Spanish Texas and California during the administration of James Polk, himself also a strong advocate of US expansionism and one of several presidents to propose purchasing Cuba from Spain.

When early US historians such as Bancroft nudged Columbus, a man who never set foot in the lands of the United States, into the first chapter of a new national saga, they essentially seized a foreign history to make it theirs, some of them fully expecting that the lands on which that history had unfolded would soon be theirs, too. Today, Americans recognize the basic story of Columbus, often unmindful of the fact that it unfolded in another America. If Columbus begins US history as written, that is partly because, consciously or unconsciously, imperial ambitions have shaped US history from the beginning, too. And Cuba—where Columbus did land—is a critical presence in that American history.

IN 1492, COLUMBUS FIRST MADE landfall not in Cuba, but on the easternmost island of the Bahamas. He immediately claimed it for Spain and christened it San Salvador, though the people already there had always called it Guanahani. Meeting them for the first time, Columbus concluded that they would make good servants and convert easily to Christianity. They rowed out to the Spanish ships in canoes, which Columbus and his men had never seen before, bearing skeins of cotton thread, parrots, darts, and things so numerous and small that he declared they would be too tedious to recount. Columbus had other things in mind. “I was attentive and took trouble to ascertain if there was gold… and by signs I was able to make out that to the south… there was a king who had great cups full.” The next day, taking several Native people to serve as guides, Columbus left Guanahani and continued his journey. He did not sail past any island without taking possession of it, something he did by merely saying it was so. To each, he gave a name, even though they already had names.8

On October 28, Columbus arrived at an island he thought looked larger than all those around it. He was right. At more than 42,000 square miles, it boasted 3,700 miles of coastline, most of it on the northern and southern coasts. The distance between its eastern- and westernmost points—some 750 miles—would be roughly equal to that between New York City and Savannah, Georgia. Some say that the island’s very long, narrow shape gives it the appearance of an alligator, one of its own native species.

Columbus landed on the island’s northeastern coast. It was, he said aloud, “the most beautiful that eyes have seen.” He spotted dogs that did not bark, unknown fruits wonderful to taste, land that was high like Sicily, mountains with peaks like beautiful mosques, and air that was scented and sweet at night. Though the people of the place called the island Cuba or Cubanacán, Columbus insisted that it was Cipangu, the name Marco Polo had given to Japan, a land awash in great riches. Unfortunately for Columbus, Cuba had no teeming cities, no golden-roofed palaces; it had no silver and no obvious sources of bountiful gold.9

Eventually, out of deference to that stubborn reality, Columbus did two things. First, he modified his original assumption. Cuba was not Cipangu, but Cathay, or mainland China. (Columbus died more than a decade later, still never having come to terms with the fact that Cuba was simply Cuba.) Second, when the island disappointed him, he did what many continue to do to this day: he left. Thirty-eight days after his arrival, he sailed away in search of more land and more gold. Undeterred, he wrote to his royal patrons as if that were no setback at all. He emphasized other forms of wealth: natural beauty and pliable Indians whose souls might be easily saved. With a confidence that came from a few weeks of exploration, he promised thriving cultivation in cotton, which could be sold in the cities of the “Gran Can, which will be discovered without doubt, and many others ruled over by other lords, who will be pleased to serve” the king and queen of Spain.10

From Cuba, Columbus headed east to another island. The people of Cuba called it Bohío or Baneque; the people of that island called it Ayiti, or land of high mountains. The Spanish would call it simply Española (in English, Hispaniola), home today to both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. On December 25, 1492, a few weeks after his arrival, one of his ships ran aground. Columbus established Europe’s first permanent settlement in the New World at the site. He called it Navidad, Christmas. A few weeks later, leaving forty men and the damaged vessel there, he departed for Spain with samples of gold, six Natives, and exciting discoveries to report.

Columbus told of the lands he had claimed for Spain—not necessarily as he found them, but embellished, as he wished them to be. Everywhere he went, people honored him as a hero. He rode on horseback next to the king, and men hurried to volunteer for his next voyage. For Columbus and the Spanish monarchs, the goal of the second expedition was to establish a permanent Spanish presence in what they thought was the heart of Asia and to use it as a base for trade, exploration, and conquest. When Columbus set sail this time, he was at the head of an expedition with seventeen ships and a contingent of about 1,500 men. There was a mapmaker, a doctor, and not one woman. While several priests joined the expedition hoping to bring their god to the Natives, most of the passengers hoped for more earthly rewards, namely gold. On that voyage, Columbus also carried sugarcane cuttings. He had no way of knowing then that sugar would hav...