![]()

PART I

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT FOR INVESTIGATIONS 1946—2014

![]()

1 Background

Christopher D Morris

1.1 Summary of previous work on the Brough of Birsay

The Brough of Birsay is a prominent tidal island at the north-west extremity of the mainland of Orkney (see Illus 0. 2). Sheer cliffs up to c. 45m high face the full force of the Atlantic storms from the west, while the ground then slopes down on the eastern face to cliffs up to 4-5m high in the central section, but rising up quite sharply to the north and more gradually along the south-western coastal perimeter towards the ‘Peerie’ (or ‘Little’) Brough (Illus 1.1). The Guardianship site as now recognised on the eastern flank of the island focuses around a small stone church and churchyard first noted and uncovered in the nineteenth century, and further settlement remains have been recognised in the twentieth century along the southwestern cliff-side margins. The geology and topography and human exploitation of the natural and agricultural resources of the Bay of Birsay, and the place of the Brough within this, have been described in the first volume (Morris 1989, 1–12), and similar descriptions are to be found in the other volumes concerned with the excavations at this site (Curle 1982, 11; Hunter 1986, 13–17). Consequently, there is no need in this volume to repeat this information.

The previous volume also looked at the historical background and the contribution of place-names to an understanding of Birsay Bay as a whole (Morris 1989, 12–21), given the detailed study that had been undertaken by Dr Hugh Marwick (Marwick 1970). Birsay as a name itself was not, however, included in his study, and it has fallen to Dr Lindsay MacGregor, quoting Jakob Jakobsen, to re-define the name in relation to the early form Byrgisey i. e. ‘the island (-ey) with a narrow neck of land (-býrgi)’ (Morris 1989, 21). ‘Brough’, of course, comes from ON borg meaning ‘fortress or stronghold’, probably in this case referring to the naturally defensive qualities of an island difficult of access, rather than a fortress such as an Iron Age broch (Morris 1989, 21, referring to Marwick 1952, 130).

Until recently, the Brough of Birsay has claimed most attention in the Birsay area (Morris 1989, 26). However, it is important to realise that, despite a well-attested tradition of pilgrimage at this site parallel to that at the Brough of Deerness (see references cited in Morris with Emery 1986a), the site itself was not as obviously impressive at close-quarters as Deerness, and the buildings at the Brough of Birsay were clearly in a far more parlous state from the end of the eighteenth century than those at the Brough of Deerness (Low in OSA 1795, 324; NSA 1845, 98) – right up to the period of it coming into ‘Guardianship’ (see Emery and Morris 1996, 209).

The Brough of Birsay has been known as a significant ecclesiastical site since its publication within the seminal work by David MacGibbon and Thomas Ross on Ecclesiastical Architecture in Scotland (1896, 135–41). It was then brought to a wider audience by L Dietrichson and Johan Meyer who emphasised its place within a Norwegian context (1906, 19–20 and 80–3). Also, in the twentieth century, senior Scandinavian archaeologists regularly visited the site and/or the excavations taking place there. For instance, Professor Jan Petersen drew attention to it in an important newspaper article in Norway (repeated in Orkney) during the pre-War investigations in 1936 (Petersen 1936), and it is clear from the official archive referred to below that Aage Roussell visited the site in 1939 (see 1.2 below). He was a Danish archaeologist who had undertaken fundamental work in Greenland, as well as writing on Norse Building Customs in the Scottish Isles (Roussell 1934; also see Roussell 1936 and 1941). This emphasis upon the Scandinavian links has been furthered by the accounts of excavations since the Second World War published in successive Proceedings of the International Viking Congresses (Cruden 1958; 1965; Hunter and Morris 1981; Hunter, Bond and Smith 1993; Morris 1993a, 66–70).

Illus 1.1 Cliffs on the north side of the Brough of Birsay (CANMORE archive: SC 1514297). © HES (John Dewar Collection)

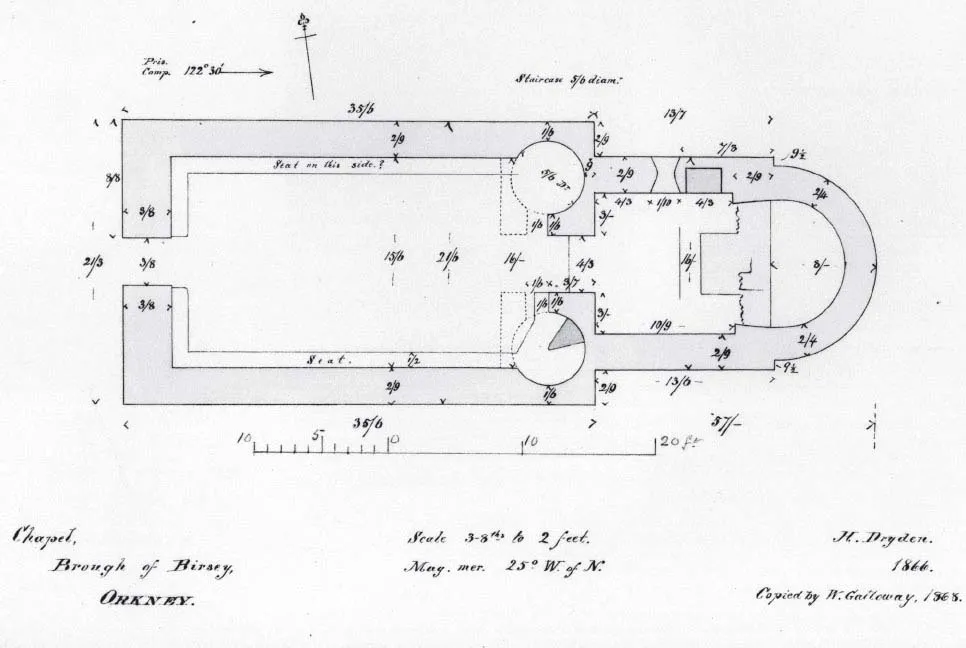

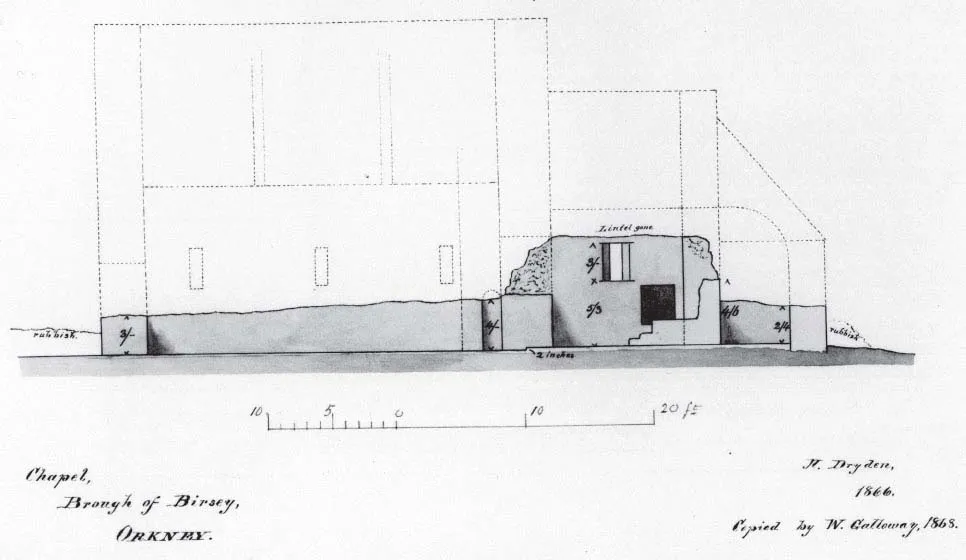

Indeed, it is entirely due to the activities of Sir Henry Dryden, as a pioneering church archaeologist in 1866 (see Dryden 1870; Dryden 1996; Morris 1996a, Appendix 3), that the site came back to the attention of scholars. Within Volume 2, Professor Richard Fawcett provided an account of the work undertaken by Dryden on the Brough of Birsay in the nineteenth century, illustrated by drawings by Dryden which were subsequently copied by William Galloway (Morris 1996a, 213–17: Illus 155–161: Illus 156 and 157 reproduced here as Illus 1.2 and 1.3), and an analysis of its significance (Fawcett 1996; see also Morris 1989, 26). The investigation by Dryden was used, virtually verbatim, thirty years later by MacGibbon and Ross (1896, 135–41). Dr Ralegh Radford’s previously unpublished summary of this work is as follows:

The Modern Exploration of the Brough of Birsay

In 1866, in the course of his tour of the northern islands, Sir Henry Dryden visited the Brough of Birsay, a tidal islet, which has long been known as the site of an early church.1 His visit marks the beginning of the exploration of this site, which has been excavated intermittently for over a century. In the year following his tour, Dryden contributed a series of notes to the Orcadian. A reprint of these notes, together with two portfolios of plans, elevations and sketches, was presented by the author to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.2 These notes and the greater number of the plans and elevations were published by MacGibbon and Ross in the first volume of the Ecclesiastical Architecture of Scotland; 3 their account was accompanied by an additional note contributed by Dryden himself.4 As this publication represents the earliest detailed record of the site, the present report covering the whole century of exploration, may conveniently begin with a reprint of the original notes…

Illus 1.2 Brough church plan (William Galloway 1868, after Sir Henry Dryden 1866: NMRS drawing SAS 26: ORD/162/2: RCAHMS archive). Reproduced from Emery and Morris 1996 Illus 156

Illus 1.3 Brough church west to east section and conjectural reconstruction (William Galloway 1868 after Sir Henry Dryden: NMRS drawing SAS 26: ORD 162/3: RCAHMS archive). Reproduced from Emery and Morris 1996 Illus 157

(CARFinal Rep 1)

Following the major publications by MacGibbon and Ross in Britain and Dietrichson and Meyer in Norway at the turn of the century, individuals such as Hugh Marwick (Marwick 1922) and John Fraser (Fraser 1925) then emphasised the importance of the site in Orkney. This was eventually recognised nationally by its inclusion in the list of those vested in the care of the State through the (then) Commissioners of Works (now, after several changes of name and vicissitudes, under HES). Even so, the state of the church building was poor in 1934. In 1921, Marwick had observed that ‘The church walls are now, for the most part, almost level with the ground…’, although he then noted that the ‘north wall of the chancel had been altered quite recently. This had probably been done in order to make a better windscreen for people taking shelter there or for the sheep that pasture on the isle’ (Marwick 1922, 67).

Similarly, very little was known of the archaeological features surrounding the church in 1934. Only nine years earlier, Fraser in fact stated that ‘…There are now few traces of the burial ground that was beside the chapel; on account of the inconvenient situation it probably was never much used’, although he did go on to note that there were ‘… some traces of…circular foundations in the vicinity of the chapel [which] may be the sites of the cells of the Culdee priests’ (1925, 25). No doubt this in part influenced the impetus for investigations from 1934, generally under the direction of Dr J S Richardson (Richardson Diary 1934), and undertaken after the site was acquired by David Swan Wallace, from the previous owner, Mr Thomas Stanger of Walkerhouse and placed it under the Guardianship of the [then] Commissioner of Works (Marwick 1922, 68; Marwick 1934; CARFinalRep1). Apart from the church site at the centre of the area handed over, no part of the site had been investigated previously, and otherwise there were merely generalised descriptions of the Brough as a fortified site, based upon, presumably, the name deriving from the ON borg = fortress, fortified place, and the very obvious occurrence of substantial masonry on the east side of the island (e.g. Marwick 1922, 67). Indeed it was assumed by Marwick and others in the early part of the twentieth century that there was a broch site here.

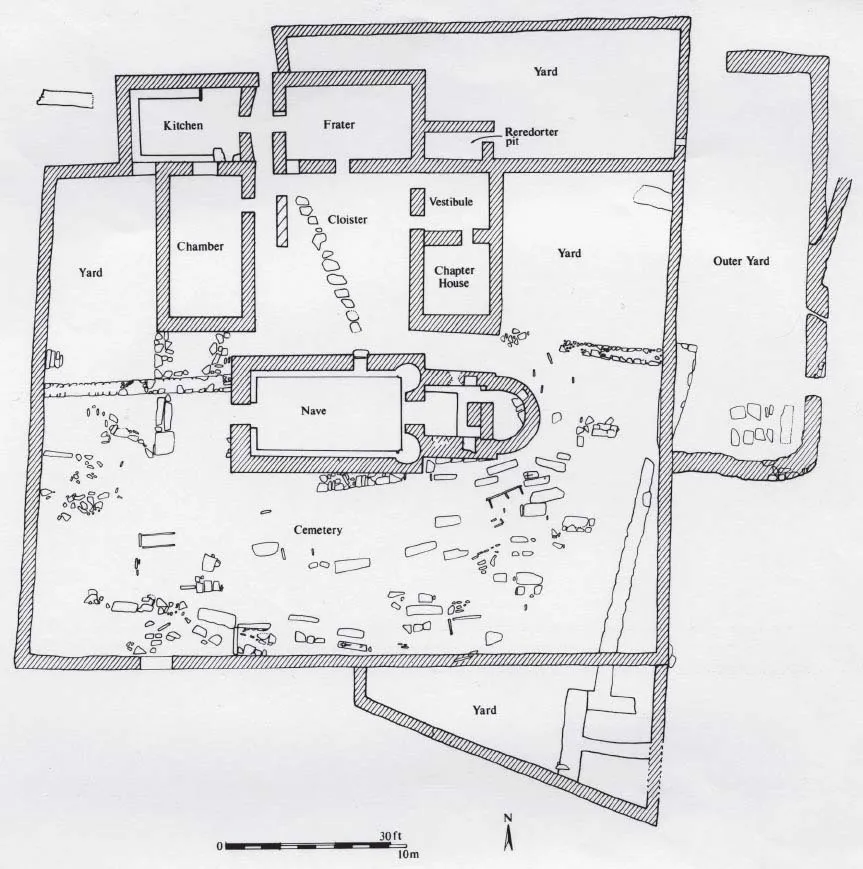

The excavations of 1934–9 explored a large proportion of the part of the Brough of Birsay which came into State care at that time and revealed structures both ecclesiastical and secular for display to the public (see Emery and Morris 1996). The investigations of the church and the apparent monastic buildings to the north (Area I) served to emphasise the importance of the site in the post-Thorfinn period of Norse Christianity, while indicating also perhaps the presence of earlier Christian activity of undefined date, and this was recognized at the time (see, for instance, Marwick 1934; Illus 1.4). The identification of buildings to the west (Area III) indicated the presence of earlier Viking period domestic secular occupation, and some industrial activity in this period – aspects which have received further attention in more recent investigations (e.g. Site F: Hunter 1986, Site VII and the author’s work reported below). To the east, where it had been assumed that there was a broch-complex (e.g. Marwick 1922, 67), there was a great complex of superimposed buildings (Area II) with deposits rich in artefacts (Curle 1982; 1983) and midden material with biological remains (Hunter and Morris 1982). These investigations indicated a continuous occupation of the site from the pre-Norse Pictish period through to the Late Norse (or even later medieval), although the earlier phases were imperfectly understood, because of the imperative to maintain structures for display to visitors.

During their survey of the monuments of Orkney, the Investigators and surveyors of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS) recorded the buildings on the Brough in March 1935. In the subsequent RCAHMS inventory for Orkney and Shetland, published in 1946, they were content to describe the later church and the building-complex to the north as a ‘medieval monastery’ (RCAHMS 1946, ii, no 1, 1–5, figs 52–7), and outlined a sequence of four stages in construction, illustrated by a plan, reproduced here as Illus 1.5 (i.e. RCAHMS 1946, II, Fig 52). It is clear from a footnote that much of their description represents Richardson’s own views at the time, based upon the work undertaken under his supervision there previously. An unpublished report prepared by him (Richardson 1946 Report) from a visit to the site on 16 June 1946 (HS official file 21859/2D/Pt I), states:

We have no knowledge of the history of the monastery unearthed by us: documentary evidence, however, may be forthcoming from Norse archives. After the Reformation there was a local tradition that a House of Trinitarian or Red Friars was located at Birsay, but the ruins bespeak a period prior to the coming of that Order into Scotland. It is likely that the monastery was built for Augustinian Canons or for Monks of the Benedictine Order, but light on this question…[may?] be forthcoming from Norway for at the time of its early occupation the Orkneys were under the ecclesiastical authority of the Archbishop of Trondhjem. Without an historic background any report on the Monastery can only be a description of the plan, and the nature of the masonry of a building devoid of mouldings or ornamentation. To this could be added an account of the various grave constructions, their contents and their stone covers that lie within the church and the cemetery. Some of these burials go back to pre-Norse times. The Monastic church and cloister are of later date than the coming of the Vikings into these parts. The evidence rests in the split fragment of a stone bearing remnants of a runic inscription which is built into the foundation of the apsidal end of the church.

(Richardson 1946 Report)

Illus 1.4 Area I Pre-War excavation plan

Similarly, the building-groups to the east of the church (Area II) were described in the RCAHMS report by Richardson (RCAHMS 1946, ii, no 6 and Fig 65, 7–8), after only one excavation season undertaken by Miss Cecil Mowbray [later Mrs Curle]. Although 13 structures were found, according to Richardson in this report these were to be seen as ‘the clustered arrangement of the dwelling on the east side of the Monastery’ (Richardson 1946 Report: Illus 1.6 labelled as ‘Site A’). Consequently, this part of the site has sometimes simply (but confusingly) been called ‘The Viking House’ by Richardson, who also stated that ‘The most difficult task that has to be undertaken is the completion of the investigations of the existing walls of the building underlying the Viking house of Greenland type’. To get to this conclusion, Richardson had clearly taken the outcome of a visit by Jan Petersen in 1936 to be that the buildings found here were all part of ‘a layout similar to what we know from Iceland and Greenland through Daniel Bruun’s account… for 1907 or Poul Nørlund’s reports from Greenland for 1930’ (Petersen 1936; discussed in Emery and Morris 1996, 226-30). By his 1946 report, this complex is described variously as ‘the walls of the Viking dwelling of Icelandic character’ and ‘the Viking house of Greenland type’ and that:

Southward of this Viking structure, and between it and a well formed boat-slip is the remains of a structure which from its features might have been a bathhouse – heaps of stones, split by water after heat had been applied to them, were found in and about this building. This method of heat and water produced the steam for the bathhous...