![]()

![]()

Ideas Roadshow conversations present a wealth of candid insights from some of the world’s leading experts, generated through a focused yet informal setting. They are explicitly designed to give non-specialists a uniquely accessible window into frontline research and scholarship that wouldn’t otherwise be encountered through standard lectures and textbooks.

Over 100 Ideas Roadshow conversations have been held since our debut in 2012, covering a wide array of topics across the arts and sciences.

See www.ideas-on-film.com/ideasroadshow for a full listing.

Copyright ©2015, 2020 Open Agenda Publishing. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-77170-087-0

Edited with an introduction by Howard Burton.

All Ideas Roadshow Conversations use Canadian spelling.

![]()

Contents

I. Scientific Beginnings

II. Inflationary Excitement

III. Progress, Tuned Appropriately

IV. Two Major Issues

V. Cosmological Denial

VI. Bouncing Back?

![]()

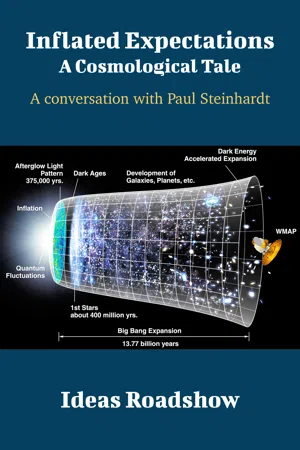

The contents of this book are based upon a filmed conversation between Howard Burton and Paul Steinhardt in Princeton, New Jersey, on May 15, 2015.

Paul Steinhardt is the Albert Einstein Professor in Science and Director of the Center for Theoretical Science at Princeton University.

Howard Burton is the creator and host of Ideas Roadshow and was Founding Executive Director of Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics.

![]()

Introduction

Not Even Wrong

Physicists are pretty good at coming up with memorable phrases to express their scientific disdain.

Einstein famously decreed, God does not play dice with the universe, as his justification for denying the inherently statistical nature of the world that quantum mechanics seemed to present.

Of course, the development of quantum mechanics was known to wreak considerable intellectual havoc among even its most significant contributors, such as Einstein. Erwin Schrödinger became so uncomfortable with the implications of his celebrated equation that he even came up with a notorious thought experiment involving a half-dead and half-alive cat to demonstrate the palpable absurdity of a standard interpretation of the theory, while plaintively summing up his view on quantum theory later on in his life with a pithy, I don’t like it, and I’m sorry I ever had anything to do with it.

Not all such dismissive remarks were specifically geared towards quantum mechanics, however. Perhaps the most notorious physics put-down is attributed to Wolfgang Pauli, who was said to have summarily rejected the work of a young physicist that was put before him by archly declaring, It is not even wrong.

Pauli’s meaning, it seems reasonable to conclude, is that the young physicist’s work was not only incorrect, it couldn’t even be coherently expressed in such a way as to be clearly and explicitly falsified. For falsification, too, is a form of scientific progress—albeit of a much less triumphant sort—that sometimes paves the way for deeper and more accurate theories.

Enter Paul Steinhardt, the Albert Einstein Professor and Director of the Center for Theoretical Science at Princeton University. Paul is a remarkably broad theoretical physicist who has made singular contributions to both cosmology and condensed matter physics. Among cosmologists he is perhaps best known for his seminal work in the early 1980s, together with Alan Guth and Andrei Linde, that led to the establishment of the theory of cosmic inflation as the primary paradigm of modern cosmology.

These days, however, Paul has decidedly broken ranks with his erstwhile inflationary colleagues, consistently drawing attention to the fact that there are deeply unsettling aspects of the theoretical framework of inflationary cosmology that should give all of us serious pause.

“Instead of driving the universe the way we had hoped from some random, initial state into a common, final condition consistent with what we observe, in fact the story of inflation is the following: it’s very hard to start; and if you do manage to start it, it produces a mess—what we call a “multiverse”—consisting of an infinitude of patches of possible, cosmic outcomes.”

Given the propensity of today’s theorists to invoke the notion of infinity, the reader might well be excused for not appreciating the seriousness of this problem. But this, Paul explains, is hardly the sort of thing to be swept under the rug, as it implies that, since any outcome is possible, there is no conceivable way we might one day be able to rule out the theory, even in principle.

Even worse still, however, sweeping it under the rug is precisely what many of his colleagues seem very much determined to do.

“I’ve had this discussion where I’ll say, ‘Well, what do you think about the multiverse problem?’ and they reply, ‘I don’t think about it.’

“So I’ll say, ‘Well, how can you not think about it? You’re doing all these calculations and you’re saying there’s some prediction of an inflationary model, but your model produces a multiverse—so it doesn’t, in fact, produce the prediction you said: it actually produces that one, together with an infinite number of other possibilities, and you can’t tell me which one’s more probable.”

“And they’ll just reply, ‘Well, I don’t like to think about the multiverse. I don’t believe it’s true.’

“So I’ll say, ‘Well, what do you mean, exactly? Which part of it don’t you believe is true? Because the inputs, the calculations you’re using—those of general relativity, quantum mechanics and quantum field theory—are the very same things you’re using to get the part of the story you wanted, so you’re going to have to explain to me how, suddenly, other implications of that very same physics can be excluded. Are you changing general relativity? No. Are you changing quantum mechanics? No. Are you changing quantum field theory? No. So why do you have a right to say that you’d just exclude thinking about it?’

“But that’s what happens, unfortunately. There’s a real sense of denial going on.”

Dogmatic denial is not terribly good for science. In fact, it could well be regarded as precisely the sort of closed-minded, unreflective attitude that the modern scientific temperament has emphatically, and so successfully, struggled against for centuries.

But it’s not just a question of scientific stubbornness. Because theorists unwilling to grapple with inflation’s “multiverse problem” aren’t simply resolutely clinging to their theory despite any objective observed support for it. As Paul points out, they are clinging to their theory independent of any observed support for it.

Take the case of the reported findings of the BICEP2 experimen...