- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

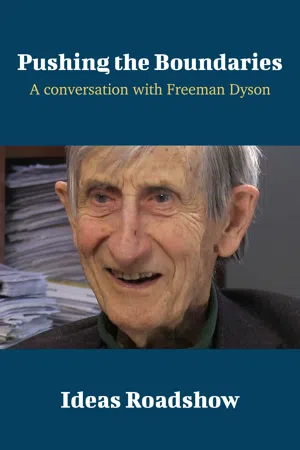

Pushing the Boundaries - A Conversation with Freeman Dyson

About this book

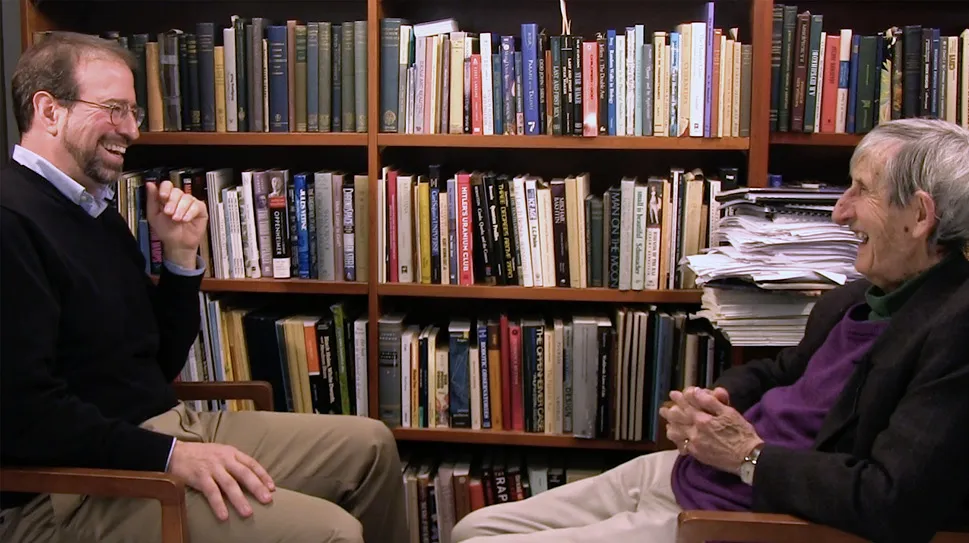

This book is based on an in-depth filmed conversation between Howard Burton and former mathematical physicist and writer Freeman Dyson, who was one of the most celebrated polymaths of our age. Freeman Dyson had his academic home for more than 60 years at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. He has reshaped thinking in fields from math to astrophysics to medicine, while pondering nuclear-propelled spaceships designed to transport human colonists to distant planets. During this extensive conversation Freeman looks back on his simultaneously transformative careers in theoretical physics, mathematics, biology, rocket ship design, nuclear disarmament and writing.This carefully-edited book includes an introduction, Pure and Applied, and questions for discussion at the end of each chapter: I. Debating Exceptionalism - Personal and professionalII. In Praise of Rebels - Moving science forwardsIII. Against Reductionism - Valuing the specificIV. Foundational Issues - From the anthropic principle to free willV. Current Mysteries - From dark energy to quasicrystalsVI. The Origin of Life - RNA as a parasiteVII. Space Travel - Manned vs. unmannedVIII. Science and Society - Climate change and moreIX. Religion - Another pathX. Final Thoughts - Neuroscience and Chinese string theoristsAbout Ideas Roadshow Conversations Series: This book is part of an expanding series of 100+ Ideas Roadshow conversations, each one presenting a wealth of candid insights from a leading expert in a focused yet informal setting to give non-specialists a uniquely accessible window into frontline research and scholarship that wouldn't otherwise be encountered through standard lectures and textbooks. For other books in this series visit website: https://ideasroadshow.com/.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

The Conversation

I. Debating Exceptionalism

Personal and professional

Table of contents

- A Note on the Text

- Introduction

- The Conversation

- Continuing the Conversation