![]()

1

WILL YOU MISS ME WHEN I’M GONE?

This wasn’t at all like home. No hearth, no front porch, just a wooden platform in a vacant building in Bristol, a mountain town on the border of Tennessee and Virginia. A recording machine powered by carefully calibrated weights, like a cuckoo clock, was nearby. Sara Carter studied the carbon microphone while Maybelle Carter quietly fingered the strings of her husband’s Stella guitar. Then, like back home in Poor Valley, they began to sing “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow,” with Sara taking the lead and Maybelle adding an alto harmony. A long moment later, as if jolted awake by a dream coming true, A. P. Carter added his bass vocal. “When we made the record and they played it back to us,” said Maybelle, “I thought, ‘Well, it can’t be!’ You know … it just seemed so unreal, that you stand there and sing and then turn around and [they] play it back to you.” The next day A. P. was absent, and the women recorded what would become the Carter Family’s first hit, “Single Girl, Married Girl.”

Ralph Peer spent twelve days in the summer of 1927 recording regional musicians in Bristol, Tennessee; the sessions have been called the big bang of country music because they introduced two seminal acts, the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers. The recording and distribution of homespun American music was not new, but the Bristol sessions confirmed that commercial records would soon supplant an oral tradition that had passed songs from one musician (and generation) to the next. Peer already had a history of recording roots music; his stint at Okeh Records produced historic examples of recorded blues (Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920) and “hillbilly” music (Fiddlin’ John Carson’s “The Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” in 1923). When Peer moved from Okeh to the Victor Talking Machine Company (soon to become RCA Victor), he negotiated a unique contract in which he took no salary but retained the publishing rights of the songs he recorded. That meant he’d earn a royalty on each record sold. In three particularly lucrative months in 1928, Peer received $250,000.

The Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers had some things in common—for one, both acts helped turn the guitar into a lead instrument—but were also quite different. “[The Carter Family’s] style was something they created out of older styles,” said musician and folklorist Mike Seeger, “with the tear between A. P.’s way-back sounds, and Maybelle’s guitar pulling them forward. But with Jimmie [Rodgers], he was reaching toward being a creator, trying to get something that would grab people’s attention—and that’s pop.”

The Carters’ repertoire was drawn from and inspired by the folk songs brought to America from the British Isles (among other places). Maybelle and A. P. draped Sara’s lead voice with church-based harmonies, and the Carter Family’s rich vocal sound stood out in an era dominated by string bands. Jimmie Rodgers was a folkie bluesman with a shape-shifting persona suitable for songs that could be randy or pious, silly or sad. Generations of folk musicians grew up singing the songs of the Carter Family. Rodgers’s personable voice and guitar informed a long line of troubadours, including Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, and Bob Dylan. “It’s arguable,” said Steve Earle, a contemporary embodiment of that tradition, “that we just wouldn’t have this consistent, lasting genre of music based on one guy singing and accompanying himself on a guitar. … I think [Jimmie Rodgers] invented the job.”

The Carter Family and Rodgers took different paths to Bristol. The Carters were borne of the passions of Alvin Pleasant Carter, known as A. P., who played the fiddle and collected folk songs as he traveled around Appalachia selling fruit trees. When A. P. married Sara Dougherty in 1915, he found both a mate and a musical partner who played guitar and autoharp and who sang with a voice of uncommon splendor. They were joined by Sara’s cousin Maybelle Addington, who created a unique guitar style (the so-called Carter scratch) by using her thumb to pick a melody on the bass strings while her fingertips created rhythms on the upper strings. “We’d get together and, you know, flump around [on our instruments], and sing,” said Sara. “Maybe go to a neighbor’s home once in a while. … It was just our natural way of playing—we don’t know any music, we just played by ear.” The Carters couldn’t read music, but they sure knew songs.

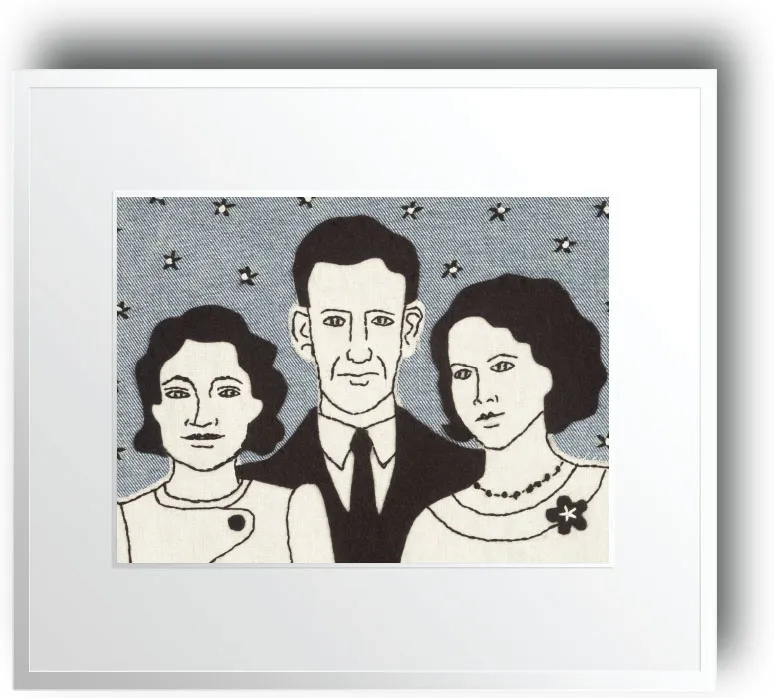

THE CARTER FAMILY

At an early performance by the Carter Family, Maybelle met A. P.’s brother Ezra, whom everybody called Eck. “I’d gone to Sara and A. P.’s to do a show at a schoolhouse,” said Maybelle. “A. P.’s brother was … going with the schoolteacher there at the school. Well, he was supposed to take her home, but he didn’t.” When Bristol beckoned, A. P. borrowed his brother’s Essex sedan after agreeing to weed Eck’s corn patch; Maybelle was eight months pregnant.

Jimmie Rodgers was born in 1897 in Meridian, Mississippi, the son of a railroad worker. His mother died when he was a child, and he ran away twice in hopes of becoming an entertainer; at fourteen, he began to learn about the blues and playing guitar while working as a water boy for a black railroad crew. Rodgers became a brakeman on the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad, but his health began to fail, and he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. At the age of twenty-eight Rodgers decided to sing for a living or die trying; one early gig found him touring with a medicine show and singing in blackface.

In Asheville, North Carolina, Rodgers recruited the Tenneva Ramblers to perform with him as the Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers. The group arrived in Bristol on August 3, 1927, but Peer recognized that Rodgers was a bright star in a mediocre string band and recorded him solo. Peer left Bristol with six tunes by the Carter Family and a pair by Rodgers (“The Soldier’s Sweetheart” and “Sleep, Baby, Sleep”) and paid the artists fifty dollars per song against a 2½-cent royalty. He encouraged them to create original material that could be copyrighted by Peer’s Southern Music Company, a move that would bring him revenue not only from their releases but more money when other artists recorded the songs. In order to maximize his influence, Peer also managed the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers.

The Carters went home to Poor Valley, nestled beneath Clinch Mountain, and presumed that little would change; but the success of “Single Girl, Married Girl” prompted Peer to schedule another session in early 1928, this time in Camden, New Jersey. Rodgers, whose first release went nowhere, was more proactive, checking into a Manhattan hotel room in November 1927 and informing Peer that he was ready to record more tunes. They cut a twelve-bar blues called “T for Texas” that featured a catchy yodel that prompted Peer to retitle the song “Blue Yodel.”

Rodgers’s background earned him the nickname “the Singing Brakeman,” but it was the bluesy yodel that became his commercial hook. “Blue Yodel” was a monster hit, and subsequent songs bore titles like “Blue Yodel No. 4 (California Blues)” and “Blue Yodel No. 8 (Mule Skinner Blues).” Rodgers’s yodel was not unlike the sob that operatic tenor (and Victor recording artist) Enrico Caruso created by changing registers during his recording of “Vesti la Giubba” from the opera Pagliacci. A more likely source was Riley Puckett, a blind singer and guitarist who played with Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers and who recorded “Sleep, Baby, Sleep,” a yodel-laden tune that Rodgers had cut in Bristol.

Rodgers’s intimate vocals anchored his records in a manner that, like hits by Bing Crosby, influenced generations of popular singers. As befits an icon, he appealed to almost everyone, including innumerable country singers and such bluesmen as B. B. King and Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett, who turned Rodgers’s yodel into a howl. Robert Johnson sang the songs of Jimmie Rodgers alongside his own. “If you believe that rock ’n’ roll brings about a nexus of black music and white music,” said Steve Earle, “then Jimmie Rodgers is one of the people who made that happen.”

Rodgers was a prolific songwriter, both by himself (“Waiting for a Train” and almost all of his thirteen Blue Yodels) and in collaboration with others. By contrast, A. P. Carter didn’t write songs so much as recognize a good one when he heard it. Returning home from his travels with tunes and stray lyrics, A. P. would work over the words and (with the help of Sara and Maybelle) craft melodies that could be copyrighted as new songs. The Carter Family’s “I’m Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes” is a telling example of the porous nature of American roots music in the first half of the twentieth century.

Maybelle and A. P. are said to have modeled the tune after “The Prisoner’s Song,” a 1925 release by Vernon Delhart. The Carter Family’s recording was a major hit in 1929; Roy Acuff heard a gospel group put different lyrics to the same melody and used those words for the 1936 song that launched his career, “The Great Speckled Bird.” Sixteen years later Hank Thompson cut “The Wild Side of Life,” in which the same tune carried new, broken-hearted lyrics about a man spotting his ex-wife in a honky-tonk. “The Wild Side of Life” stayed at the top of the country charts for fifteen weeks. Then songwriter J. D. Miller used the same melody to create an “answer song” that became the #1 hit that introduced the world to Kitty Wells, “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.”

Peer’s output at Victor also included tracks by black musicians (known as “race records”) by such southern blues musicians as Tommy Johnson, Furry Lewis, and Sleepy John Estes. He also recorded such seminal ensembles as Will Shade’s Memphis Jug Band and Gus Cannon’s Jug Stompers. Bluesmen like Son House and Skip James recorded for Paramount Records in 1931 but remained virtually unknown until they became rediscovered stars of the blues revival of the 1960s. That group also included Mississippi John Hurt, a guitarist and singer who recorded for Okeh Records in 1929 and whose repertoire of blues and folk tunes was not unlike those of Rodgers and the Carter Family.

Roots music was also of interest to folklorists who recorded music not for profit but to document regional styles before they disappeared. In 1933 John Lomax, an author and musicologist, made field recordings for the Library of Congress with his son Alan. The pair discovered and recorded Huddie Ledbetter at the Louisiana State Prison in Angola. Ledbetter, who’d already served time for murder, was in prison for stabbing a white man. Released two years later, he would soon come to be known as the folk singer Lead Belly. Alan would subsequently establish his own relationship with the Library of Congress and in 1941 would record McKinley Morganfield, already known as Muddy Waters, at Stovall Plantation.

Singing into Lomax’s microphone, Waters performed “Country Blues,” which was his version of Robert Johnson’s “Walking Blues,” which was Johnson’s rewrite of Son House’s “My Black Mama.” A. P. Carter could relate to the way Delta blues musicians created new songs using familiar guitar licks and lyrical fragments. And Sara Carter would understand how Waters felt when Lomax played back the recording to him. “Man, you don’t know how I felt that Saturday afternoon when I heard that voice and it was my own voice,” said Waters. “Later on he sent me two copies of the pressing and a check for twenty bucks, and I carried that record up to the corner and put it on the jukebox. Just played it and played it and said, ‘I can do it, I can do it.’” By the late 1940s, Waters would be in Chicago reshaping his delta music into a whole new style of big-city blues.

Jimmie Rodgers couldn’t wait around to become famous; living with tuberculosis, he already knew his days were numbered when he traveled to Bristol. If Peer personified the modern record man, Rodgers was like a pop star. Recording 111 songs in just five years, Rodgers was an avid self-promoter, quick to sign autographs and talk up deejays and reporters while he was on concert tours. He sat for numerous photo shoots in a variety of outfits and snappy hats, filmed a promotional movie short for Columbia Pictures called The Singing Brakeman, recorded with superstar colleagues such as the Carter Family and jazzman Louis Armstrong, and toured with showbiz cowboy and humorist Will Rogers to benefit the Red Cross. In a word, Rodgers was the Bono of his time.

But time was short for one of the biggest stars of his day. In May 1933 Rodgers traveled to New York for what would be his last recording session. A cot was brought to the studio so that he could lie down between takes. In four sessions held over the course of a week, Rodgers recorded eleven songs; the words of the last one, “Years Ago,” spoke to being sad to leave Mississippi. The next day, Rodgers and his private nurse took a trip to Coney Island; feeling distress, he returned to the Taft Hotel, where five years earlier he had stayed while hustling a second chance with Ralph Peer. Rodgers died late that night. The body was brought back to Mississippi by rail, and as the night train pulled into Meridian, the mournful cry of the locomotive’s whistle welcomed the brakeman home.

Jimmie Rodgers inspired a school of emulators. Gene Autry spent the late 1920s releasing virtual copies of Rodgers’s “Blue Yodels” and was quick to cut a tribute song, “The Death of Jimmie Rodgers.” Autry soon found his own mellifluous style and became Hollywood’s premiere singing cowboy. Ernest Tubb was another fan; Carrie Rodgers gave Tubb one of her late husband’s guitars and helped him obtain a contract with RCA. Like Autry, Tubb didn’t click until he established his own sound, in his case with 1940’s “Walking the Floor Over You.” Future country stars like Lefty Frizzell and Johnny Cash grew up idolizing Rodgers. The first tune Doc Watson learned to play on guitar was the Carter Family’s “When the Roses Bloom in Dixieland,” but he started using a flat pick after listening to Jimmie Rodgers.

Others didn’t imitate Rodgers so much as interpret his songs in new ways. Bill Monroe and his brother Charlie recorded in the 1930s as the Monroe Brothers. When that group broke up, Bill formed the Blue Grass Boys. Monroe, who played mandolin, had learned the syncopations of blues and jazz from a black guitarist named Arnold Schultz; these rhythmic touches became his special sauce. Monroe’s group used fast tempos and high-pitched vocal harmonies to create a lively string-band style that came to be called bluegrass. Monroe became known as the “Father of Bluegrass” with the mid-1940s lineup that included guitarist Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, who used a unique three-fingered technique to pick his banjo. But in 1939, when Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys successfully auditioned for the Grand Ole Opry program in Nashville, they played Jimmie Rodgers’s “Mule Skinner Blues.” “Charlie and I had a country beat,” said Monroe, “but the beat in my music—bluegrass music—started when I ran across ‘Mule Skinner Blues’ and started playing that. We don’t do it the way Jimmie sang it. It’s speeded up, and we moved it up to fit the fiddle, and we have that straight time with it—driving time.”

On the day in 1940 when Monroe recorded “Mule Skinner Blues,” the Blue Grass Boys also cut “I Wonder If You Feel the Way I Do” by Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, who in 1938 counted fourteen members including three fiddles, two saxophones, a trumpet, and a drummer. The band did big business in the Southwest and kept the dance floor hopping with its big-band style of country music. Wills recognized that a Jimmie Rodgers tune could kill with a big beat, rhythmically bowed fiddles, jazzy improvisations on the pedal steel, and smoothly swinging vocals (delivered most famously by Tommy Duncan).

Willie Nelson, a Texas teenager who played music in a combo with his sister Bobbi and her husband Bud Fletcher, staged a Bob Wills concert not far from his childhood home in Abbott. Nelson figures that about five hundred people came to the show; the gate receipts barely covered the band’s guarantee and left nothing for the young promoter, whose group was the opening act. “He hit the bandstand at eight and didn’t leave it for hours,” said Nelson of Wills. “He would play continually, there was no time wasted between songs. … His band watched him all the time, and he only had to nod or point the bow of his fiddle to cue band members to play a solo. He was the greatest dance hall bandleader ever.”

Wills ruled a Southwest music scene full of talent. The Maddox Brothers and Rose, a popular swing band that called its version of the Rodgers song “New Muleskinner Blues,” traveled the rodeo circuit to play the local bars. “Right across the street from us would always be Woody Guthrie,” said Rose Maddox. “I was a kid. He looked tall and skinny.” Guthrie, the enduring archetype of the socially conscious folk singer, took up music as a teenager and led a life of wanderlust that included three wives and eight children. During the late 1930s he performed on KFVD, a radio station in Los Angeles, and debuted songs that would appear on his 1940 RCA release, Dust Bowl Ballads. He also wrote a column called “Woody Sez” for a Communist newspaper, People’s World, a sideline that ultimately cost the “fellow traveler” his radio job.

At the request of Alan Lomax, Guthrie traveled to New York to perform at “A ‘Grapes of Wrath’ Evening for the Benefit of the John Steinbeck Committee for Agricultural Workers.” Lomax subsequently recorded hours of Guthrie’s conversation and songs for the Library of Congress. “The first hint of his real importance didn’t come from him or me,” said his third wife, Marjorie Guthrie. “It was Alan Lomax who said to me, ‘Don’t throw anything away. Save everything.’ And I looked at him to say, ‘Why?’ And he said, ‘Woody is going to be very important.’”

At the benefit, Guthrie met a folk singer who worked for Lomax: Pete Seeger. “I learned a lot about songwriting from Woody,” said Seeger, a Harvard dropout who was the son of composer and musicol...