eBook - ePub

A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes

A Son's Memoir of Gabriel Garc?a Marquez and Mercedes Barcha

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes

A Son's Memoir of Gabriel Garc?a Marquez and Mercedes Barcha

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

When my brother and I were children, my father made us promise to spend New Year’s Eve of the year 2000 with him. He reminded us of that commitment several times throughout our adolescence, and his insistence was embarrassing to me. I eventually came to interpret it as his wish to still be alive on that date. He would be seventy-two, I would be forty, the twentieth century would come to an end. Those milestones could not seem further away when I was a teen. After my brother and I became adults, the promise was seldom mentioned, but we were indeed all together the night of the new millennium in my father’s favorite city, Cartagena de Indias. “We had a deal, you and I,” my father said to me shyly, perhaps then also somewhat embarrassed by his insistence. “That’s right,” I said, and we never spoke of it again. He lived another fifteen years.

When he was in his late sixties, I asked him what he thought about at night, after he turned out the lights. “I think that things are almost over.” Then he added with a smile, “But there’s still time. No need to get too worried just yet.” His optimism was genuine, not just an attempt to comfort me. “You wake up one day and you’re old. Just like that, with no warning. It’s stunning,” he added. “I heard years ago that there comes a time in the life of a writer when you are no longer able to write a long work of fiction. The head can no longer hold the vast architecture or navigate the perilous crossing of a lengthy novel. It’s true. I can feel it now. So it will be shorter pieces from now on.”

When he was eighty, I asked him what that was like.

“The view from eighty is astonishing, really. And the end is near.”

“Are you afraid?”

“It makes me immensely sad.”

When I think back on these moments, I am genuinely moved by how forthcoming he was, especially given the cruelty of the questions.

2

I call my mother on a weekday morning in March 2014, and she tells me that my father has been in bed with a cold for two days. This is not unusual for him, but she assures me that this time it’s different. “He’s not eating, and he won’t get up. He’s not himself. He’s listless. Álvaro started like this,” she adds, referring to a friend of my father’s generation who died the previous year. “We’re not getting out of this one” is her prognosis. After the call I am not alarmed, since my mother’s forecast can be attributed to anxiety. She is well into a period of her life when old friends are dying with some frequency. And she’s been hard hit by the recent loss of siblings, two of her youngest and dearest. Still, the call makes my imagination take flight. Is this how the end begins?

My mother, twice a cancer survivor, is due in Los Angeles for medical tests, so it is decided that my brother will fly in from Paris, where he lives, to Mexico City to be with our father. I will be with our mother in California. As soon as my brother arrives, my father’s cardiologist and principal doctor tells him that my father has pneumonia and that the team would feel much more at ease if they could hospitalize him for further tests. It appears he had been suggesting that to my mother for at least a few days but that she had been reluctant. Perhaps she was scared of what a proper physical exam would uncover.

3

Phone conversations with my brother over the next few days allow me to form a picture of the hospital stay. When my brother checks my father in, the administrator jumps in her seat with excitement when she hears his name. “Oh, my God, the writer? Would you mind if I call my sister-in-law and tell her? She has to hear about this.” He entreats her not to, and she yields, reluctantly. My father is placed in a relatively isolated room at one end of a hallway to protect his privacy, but within half a day doctors, nurses, orderlies, technicians, other patients, maintenance and cleaning personnel, and perhaps the administrator’s sister-in-law make their way past his door to catch a glimpse of him. The hospital responds by limiting access to the area. Journalists have also begun to gather outside the main gate of the hospital, and the news is published that he is in grave condition. It’s undeniable that we’re being spoken to loud and clear: my father’s illness will be partly a public affair. We cannot shut the door completely because much of the curiosity about him is from concern, admiration, and affection. When my brother and I were kids, our parents invariably referred to us, accurately or not, as the most well-behaved children in the world, so that expectation must be fulfilled. We must respond to this challenge, whether we have the strength for it or not, with civility and gratitude. We will need to do that while keeping my mother satisfied that the line between the public and the private, wherever we determine it to be given the circumstances, is strictly enforced. This has always been of enormous importance to her despite, or maybe because of, her addiction to the most salacious gossip shows on television. “We are not public figures,” she likes to remind us. I know that I will not publish this memoir until she is unable to read it.

My brother has not seen my father for two months and finds him more disoriented than usual. My father doesn’t recognize him and is anxious that he doesn’t know where he is. He is put somewhat at ease by his driver and secretary, who take turns visiting with him, and one of them or the cook or the housekeeper spends the night with him at the hospital. There’s no point in my brother staying because my father needs a more familiar face if he wakes up in the middle of the night. The doctors ask my brother how my father seems compared to a few weeks ago, since they cannot tell whether his state of mind is a product of his dementia or of his present weakness. He is making little sense and is unable to answer simple questions coherently. My brother confirms that although he seems somewhat worse, this is mostly how he has been for many months now.

This is one of the principal teaching hospitals in the country, so promptly the first morning a doctor comes around, shepherding a dozen interns. They cluster around the foot of the bed and listen as the doctor reviews the patient’s condition and treatment, and it’s clear to my brother that the young physicians had no idea whose room they had entered. Their growing realization can be seen from face to face as they observe him with weakly concealed curiosity. When the doctor asks if there are any questions, they all shake their heads no and follow him out like ducklings.

At least twice a day, as my brother leaves or arrives at the hospital, the crowd of reporters calls out to him. He is as unfailingly polite as a gentleman of the early nineteenth century and therefore constitutionally incapable of ignoring a human being who addresses him directly. So when asked, “Gonzalo, how is your father doing today?” he feels compelled to approach the group and becomes ensnared in an impromptu press conference. I see clips of it on television, and he is very capably, if tensely, working his way through it, fueled by sheer discipline. I encourage him to end this practice. I explain that when you see a photograph of a movie star walking sullenly out of a coffee shop, head bowed and ignoring the world around her, she is not being rude or arrogant. She is merely attempting to reach her car as quickly as possible with some dignity. He listens to me with the trepidation of someone being convinced to participate in a crime. When he finally adopts my recommendation, it is not without guilt, but after a little practice he admits that he could, in time, warm up to some of the heathen customs of show business.

Our father’s pneumonia is responding to treatment, but scans reveal liquid accumulating in the pleural region as well as suspicious-looking areas in his lung and liver. These are not inconsistent with malignant tumors, but the doctors are reluctant to speculate without biopsies. The areas in question are difficult to access, so tissue would have to be collected under general anesthetic. Given his present state, there’s the possibility that afterward he would be unable to breathe on his own and would be put on a respirator. It’s the stuff of medical television shows, elementary but no less overwhelming. In Los Angeles, I present the situation to my mom, and as expected, she says no to a respirator. So no surgery and no biopsies and, without a cancer diagnosis, no treatment.

My brother and I discuss it and decide he should attempt to lean on one of the doctors, the resident or the lung surgeon perhaps, and force them to offer a prediction. My brother asks: “If either the lung or liver present malignant tumors”—if, always if—“what would be the prognosis?” He would have a few months, maybe longer, but only with chemotherapy. I describe the situation and symptoms to my father’s oncologist and friend in Los Angeles, and he says very calmly, “It’s possibly lung cancer.” Then he adds, “If that’s what they suspect, take him home and make him comfortable and, whatever you do, never take him back to the hospital. The hospital stay will beat up all of you.” I consult with my father-in-law in Mexico, also a physician, and his reaction is generally the same: stay away from the hospital, make it easier for my father and for us all.

4

I have to talk to my mother and confirm her worst fears that her husband of over half a century is terminally ill. I wait until we are alone on a Saturday morning. I start to explain the situation by summing up deliberately what we’ve been through and where we are now, and she listens and looks at me with what seems like mild disinterest, drowsily, as if she’s hearing a story she’s heard many times before. But when I get to the bottom line, I try to be brief and precise: it’s very likely lung or liver cancer, or both, and he has only a few months to live. Before her expression betrays anything, her phone rings and she picks it up, which takes me completely by surprise. I observe her, stupefied, while she talks to someone in Spain, and I marvel at this living, breathing, textbook example of avoidance. It is, in its own way, beautiful as well as endearing. For all her strength and resources, she is just like everyone else. She keeps the call brief and hangs up and turns to me calmly and says, “And so?” as if we’re discussing whether it’s better to take an avenue or a side street. “Gonzalo will take him home the day after tomorrow. We should fly back to Mexico.” She nods, taking it all in, then asks: “So this is it? For your father?”

“Yes, it seems that way.”

“Madre mía,” she says and lights up her electronic cigarette.

5

Writing about the death of loved ones must be about as old as writing itself, and yet the inclination to do it instantly ties me up in knots. I am appalled that I am thinking of taking notes, ashamed as I take notes, disappointed in myself as I revise notes. What makes matters emotionally turbulent is the fact that my father is a famous person. Beneath the need to write may lurk the temptation to advance one’s own fame in the age of vulgarity. Perhaps it might be better to resist the call and to stay humble. Humility is, after all, my favorite form of vanity. But as with most writing, the subject matter choses you, and so resistance could be futile.

A few months earlier a friend asked how my dad was doing with his loss of memory. I told her he lives strictly in the present, unburdened by the past, free of expectations for the future. Forecasting based on previous experience, which is believed to be of evolutionary significance as well as one of the origins of storytelling, no longer plays a part in his life.

“So he doesn’t know he’s mortal,” she concluded. “Lucky him.”

Of course, the picture I painted for her is simplified. It is dramatized. The past still plays a part in his conscious life. He relies on the distant echo of his considerable interpersonal skills to ask anyone he meets a series of safe questions: “How is everything?” “Where are you living these days?” “How are your people?” Occasionally he’ll venture an attempt at a more ambitious exchange and become disoriented in the middle of it, losing the thread of the idea or running out of words. The puzzled expression on his face, as well as the embarrassment that crosses it momentarily, like a puff of smoke in a breeze, betrays a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Part Four

- Part Five

- Acknowledgments

- Photographs

- Chronology

- Selected Bibliography

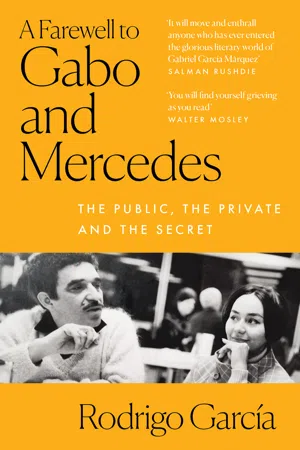

- A Note on the Cover

- About the Author

- About the Publisher

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes by Rodrigo Garcia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.