1

Spreading Disease, or Inoculating Us from Intolerance?

Throughout the height of the disease the body would not waste away but would hold out against the distress beyond all expectation. The majority succumbed to the internal heat before their strength was entirely exhausted, on the seventh or ninth day. Or else, if they survived, the plague would descend to the bowels, where severe lesions would form, together with an attack of uniformly fluid diarrhea which in most cases ended in death through exhaustion. Thus the malady which first settle in the head passed through the whole body, starting at the top. And if the patient recovered from the worst effects, symptoms appeared in the form of a seizure of the extremities: the privy parts and the tips of the fingers and toes were attacked, and many survived with the loss of these, others with the loss of their eyes. Some rose from their beds with a total and immediate loss of memory, unable to recall their own names or to recognize their next of kin.1

Thucydides

I completed the first draft of this book in a kind of paradisal isolation, as a Rockefeller Foundation Writing Resident in Bellagio, Italy. Writing a book about the Great Tradition of literature on a property with a cultural history that dates back to at least the fifth century BC felt particularly auspicious. According to Pilar Palaciá and Elisabetta Rurali,2 the American Principessa del la Torre e Tasso, better known as Ella Holbrook Walker (the inheritor of the Johnny Walker fortune), offered her Italian villa to the Rockefeller Foundation ‘for purposes connected with the promotion of international understanding’. In making the gift, she insisted that the contents remain for use in the villa, rather than being stored or sold. This means that those fortunate enough to visit or reside therein are surrounded by extraordinary artworks which, combined with the fascinating history of the building itself, fill the air with the power, beauty and weightiness of history. This was an auspicious setting in which to write about the Great Tradition of literature!

I then spent two years seeking further documentation, primary literatures and examples from the realm of international refugee law, to find concordances between the Great Books and the challenges faced by migrants seeking protection from persecution. Thanks to a Canada Research Chair, I then spent a year in Ottawa, Canada with minimal teaching or administrative responsibilities, which allowed me to assemble the documents and ideas required for such an ambitious project. The wintertime of 2020 brought an abundance of calm reflection, and I sat for many hours in front of our wood-burning fireplace, revisiting each of the chapters of the book leading up to this one, on ‘spreading disease’. As I quietly pursued my work, unsettling news was trickling in from China, beginning in the first days and weeks of 2020. We now know that on 31 December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) China Country Office was informed of cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology detected in Hubei Province of China. The outbreak was said to have begun in a seafood and poultry market in Wuhan, a city of 11 million in central China. Like SARS and MERS-CoV, the newly detected coronavirus had a zoonotic source, but human-to-human transmission was confirmed in January. By 11 March 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 viral disease a pandemic. Suddenly, the texts to which I had referred for this chapter in particular seemed not just true-to-life, but positively autobiographical.

The news reports grew increasingly horrendous through the late winter and early springtime months. We were all called upon to self-isolate, and halt our travel from Ontario – even to the adjacent province of Québec. This didn’t impose upon me restrictions that I had not already imposed upon myself, but when I stepped out into the snow-covered city of Ottawa, I found that the entire area had joined me in the lockdown. The streets were virtually isolated, traffic in and around Ottawa came to a standstill, flights were all cancelled, and most stores, particularly local venues, were shuttered. Time slowed down, and at first it was a rather joyful respite from the usual hustle-and-bustle of life in a country capital. But as the springtime sunshine began to melt the mountains of snow, neighbours who were weary of the isolation and anxious to re-start their lives began to venture out of doors. Shops began to open, cautiously, while others remained closed, or were migrated to online spaces. The news wasn’t good, particularly for elderly populations in nursing homes. The initial sense of disbelief about the dangers that the virus posed morphed into grief and sorrow for the growing numbers of people reported to have died as a result of contact with the virus.

Weeks went by, and then months, and as people recognised the methods and rates of transmission across an array of borders, sadness slowly transformed into frustration, and even anger, fuelled by the sense that things could have been done differently in the early days of the outbreak. Canada’s social security system ensured that most citizens felt somewhat protected from the plunging markets and rapidly growing rates of unemployment, but reports from the United States told stories of heightened resentment amongst those who felt that their governments had gone ‘too far’, that the numbers of dead and dying didn’t justify the measures taken. Moreover, that people needed to get back to work, to shopping, to nail salons, to beaches and to tattoo parlours. The chasm between our experience in Canada, what we were hearing from Europe, and what we were learning about our Southern neighbours, grew. But my own chasm, between what I was experiencing and what I was reading about in order to write this chapter, diminished. And soon, I felt as though the books from the Great Tradition were as illuminating, and in some cases far more insightful, than the cacophony of current news stories. The reports from the Center for Disease Control (CDC),3 the WHO4 and the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) sites5 that reported Covid-19 illness, death and news thereabout, were all replete with updated facts about the pandemic. But the stories, to which we’ll now turn, often provided more penetrating insights into what it felt like to live during this public health disaster.

I.Pandemics in Literature and Culture

Some of the most trenchant stories reported in contemporary media sources were those written by healthcare professionals, particularly those who, through their work on the frontlines, had become infected. For example, Dr Ahmed Hankir, Academic Clinical Fellow in General Adult Psychiatry at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, wrote in the Psychiatric Times6 about his experiences treating, and then suffering from, Covid-19. He begins by describing his vulnerability to the disease on account of the shortages, and flimsiness of, personal protective equipment (PPE). No matter, for him it was essential to ‘go in’, notwithstanding his apprehensions about his preparedness. As it happened, his anxieties were not unfounded.

After working on the new COVID-19 ward in our hospital I had a high temperature, fatigue, generalized aches and pains, and malaise. So here I am in my room in South London on day 6 of self-isolation composing this article waiting for the COVID-19 self-testing kit to be posted to my address by Amazon courtesy of her Majesty’s Government.7

Dr Hankir felt that it was his ‘duty’ to care for his patients, and once infected he responded to another call, to document his experience with the illness:

I’m actually feeling extremely fortunate; my symptoms have almost completely resolved after plenty of rest, fluids, and paracetamol. I’ve convalesced and I’m very much looking forward to returning to work to provide care to patients with mental illness during the pandemic. I miss interacting with patients and the camaraderie that I experienced with my colleagues. I think about the people who have tragically died (as of April 25, 2020 over 20,000 deaths related to COVID-19 have been recorded in the UK, the fifth nation to surpass that grim figure), their loved ones, those with more severe symptoms, and the patients on ventilators who are fighting for their lives. I think about the health care professionals who made the ultimate sacrifice and died while treating patients with COVID-19.8

The more circumspect reporting about pandemics, in such outlets as the London Review of Books, the Public Domain Review, Salon Magazine, The Paris Review, The New Yorker and elsewhere, supplemented this kind of real-world reporting with references to the Great Books corpus of literature that I was reading. It was powerful to read Dr Hankir’s report from his own experiences, and then strangely illuminating to connect his experience to those of characters who were created in distant lands hundreds or even thousands of years ago.

For example, it was fascinating, in light of reports I was reading about the source of Covid-19, to read speculation about possible sources of earlier plagues, blights and pandemics. The current virus may have jumped from animal species to humans on account of vendors, who brought together animals who weren’t in contact in the same way in nature. Or perhaps it was the bats who infected people, because their natural habitat had been destroyed by human incursions and climate change. Neither explanation was far from the speculation about plagues, blights and diseases that are found in the Great Books. As far back as Ancient Greece, and undoubtedly further, there was a sense that pandemics like Covid-19 were caused by moral failure that incurred the wrath of the gods, or by humans overstepping the bounds of acceptable behaviour, leading Mother Nature to impose penalties.

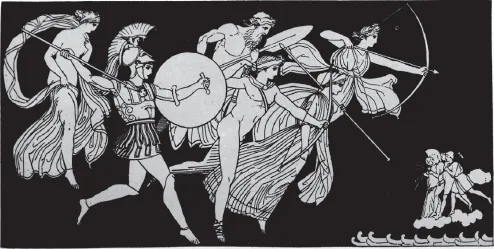

Figure 1.1 Alfred John Church (author), John Flaxman (illustrator), The Gods Descending to Battle, 1895 from Homer’s Iliad

Source: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Story_of_the_Iliad#/media/File:The_Gods_descending_to_battle.webp.

One of the earliest books known, Homer’s Iliad (762 BC), begins with a sickness striking Greek troops beneath the walls of Troy, most likely a sign that their siege of the city is wrong, and the outcome destined to be a disaster. The sickness caused by these ill-fated warriors is referred to at different points in the first book as nousos, loimos and loigus – ‘a disease, an outrage or injury, and a disaster or devastation’.9 Was Covid-19 the result of a similar outrage, for which an injured Mother Nature exacted payment? Or was this a confluence of signs, connecting inward turmoil, portentous predictions, and the outward manifestation of danger through disease?10 It was only in the unfolding of Homer’s narrative that those who had tried to understand the events could interpret the meaning of each sign, after the fact. This is not unlike the process of interpreting symptoms shown in a patient, because early manifestations of an illness are so similar, even in such dramatically different illnesses as (say) a mild cold and the Covid-19. Modern day doctors, like readers of signs in the Iliad, have to determine what they are looking at, and connect it to what they know about the world.

A.The Arc of Disease, Suffering and Death

First-person recollections about plagues and pandemics tend to follow a similar trajectory, whether they date back to Ancient Greece, or to the early reports about the novel coronavirus. In each case, reports begin with some signs of trouble early on, followed by expressions of concern amongst the ‘experts’, disbelief amongst a population who has heard about a suspicious illness, and then the sense, or perhaps the hope, that it will stay ‘over there’, across some kind of physical, spiritual or official border. Then come concerning reports about people dying of that same illness in ever-growing numbers, and the fear that travellers may be spreading the disease by voyaging to other regions. In the current era of highspeed travel for business, or to cross far-flung destinations off those proverbial ‘bucket...