- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

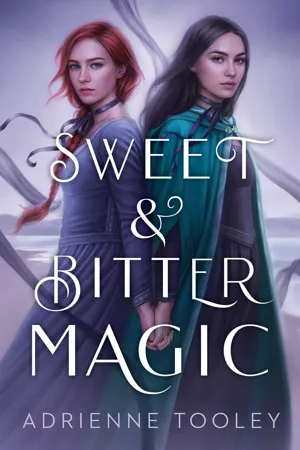

Sweet & Bitter Magic

About this book

In this charming debut fantasy perfect for fans of Sorcery of Thorns and Girls of Paper and Fire, a witch cursed to never love meets a girl hiding her own dangerous magic, and the two strike a dangerous bargain to save their queendom.

Tamsin is the most powerful witch of her generation. But after committing the worst magical sin, she’s exiled by the ruling Coven and cursed with the inability to love. The only way she can get those feelings back—even for just a little while—is to steal love from others.

Wren is a source—a rare kind of person who is made of magic, despite being unable to use it herself. Sources are required to train with the Coven as soon as they discover their abilities, but Wren—the only caretaker to her ailing father—has spent her life hiding her secret.

When a magical plague ravages the queendom, Wren’s father falls victim. To save him, Wren proposes a bargain: if Tamsin will help her catch the dark witch responsible for creating the plague, then Wren will give Tamsin her love for her father.

Of course, love bargains are a tricky thing, and these two have a long, perilous journey ahead of them—that is, if they don’t kill each other first.

Tamsin is the most powerful witch of her generation. But after committing the worst magical sin, she’s exiled by the ruling Coven and cursed with the inability to love. The only way she can get those feelings back—even for just a little while—is to steal love from others.

Wren is a source—a rare kind of person who is made of magic, despite being unable to use it herself. Sources are required to train with the Coven as soon as they discover their abilities, but Wren—the only caretaker to her ailing father—has spent her life hiding her secret.

When a magical plague ravages the queendom, Wren’s father falls victim. To save him, Wren proposes a bargain: if Tamsin will help her catch the dark witch responsible for creating the plague, then Wren will give Tamsin her love for her father.

Of course, love bargains are a tricky thing, and these two have a long, perilous journey ahead of them—that is, if they don’t kill each other first.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

Margaret K. McElderry BooksYear

2021Print ISBN

9781534453869eBook ISBN

9781534453876ONE TAMSIN

The salt was dull on Tamsin’s tongue. The mild spice had meant something to her once, had made a difference when sprinkled with a deft hand on her boiled eggs or her smoked fish. Now it tasted like everything else, in that it tasted like despair, like the whisper of a faraway fire. Like the rest of her stale, wasted life.

The woman was staring at Tamsin expectantly. Tamsin shook her head. “The salt from your tears is useless to me.” She forced the small brown pouch back into the trembling woman’s hand.

“But my nursemaid said… this is the same price she paid the witch in Wells.” The woman’s eyes looked ready to spill more salt.

Tamsin blinked, her face blank as a slate. “Go to the witch in Wells, then.”

She knew the woman wouldn’t. Tamsin was twelve times more powerful than the witch in Wells, and everyone, including the simpering woman standing before her, knew it.

The woman’s eyes grew wide. “But my child.”

She held out the unmoving bundle in her arms. Tamsin ignored it, turning toward the fireplace, which had been stoked to a blazing roar despite the midsummer heat. The flames danced merrily. Mockingly. The fire did nothing to shake the chill in Tamsin’s bones. She pulled her shawl tighter, swept her long hair around her, but it made not a single bit of difference. She was freezing.

The fire crackled. The woman wept. Tamsin waited.

“Please.” The woman’s voice caught at the end of the word, her plea transformed into a cough, a desperate whimper. “Please save my son.”

But Tamsin did not turn. The woman was so close—so close to uttering the three words Tamsin needed to hear.

“I’ll do anything.”

Tamsin’s lips curled. She turned, gesturing for the woman to hand over the bundle of blankets. The woman hesitated, eyes darting nervously over the objects assembled on Tamsin’s cluttered wooden table: hazy, sharp-edged crystals; bundles of sage and lavender tied with white string; thick, leather-bound books with creamy, black-inked pages.

Tamsin needed none of those things, of course. Witches themselves were the vessels, intermediaries siphoning natural magic from the world around them and nudging it in the right direction.

Still, in her nearly five years serving the townspeople of Ladaugh, Tamsin had found that most of them felt more at ease in her cottage when they had something concrete to focus on. Something that wasn’t her.

The baby didn’t stir when he was transferred from his mother’s arms to Tamsin’s. Tamsin used a finger to push aside the blanket obscuring his tiny face. He was a sickly yellow gray, the color stark against Tamsin’s pale skin. His little body was so feverish she could almost feel its heat. His temperature was much too high for his tiny heart to handle.

Tamsin murmured a few soft nonsense words to the child. Then she glanced up at his mother, almost as if she had forgotten.

“Oh. My payment.” Tamsin tried to situate her face in such a way to appear casual. Apologetic. “I’ll simply need you to part with some of your love.”

She considered the two children before her. Although the woman had braved Tamsin’s cottage out of devotion to her son, the emotional bond between mother and daughter had existed for two additional years. That level of unconditional love would last Tamsin much longer than a bond to a child barely three months old.

“The love for your daughter would be best.” Tamsin gestured to the little girl, who was examining the crystals with wide, thoughtful eyes.

The woman blanched, her face turning nearly as gray as her son’s. “You cannot be serious.”

Tamsin shrugged, rocking the baby gently. “I’m afraid those are my terms. Surely you’ve heard whispers at the market.”

She did her best not to waver. It was just as unconscionable a request as the woman’s face reflected. Other witches worked for the price of a baby’s laugh, for fresh bread, for a new pewter cauldron. Yet love was Tamsin’s price.

It was the only way to defy the curse that had been placed upon her nearly five years prior.

Tamsin could no longer love, and therefore was doomed never to feel any of the joys life had to offer. She could only get a glimpse of what she had lost by taking love from another. If she held tight—and the person’s love was pure—it was enough to give her a few moments of feeling. To experience the warmth of the world despite the cold uselessness of her heart.

The woman’s eyes had gone blank, and when she spoke, it was softly, as if to herself. “They warned me, but I couldn’t believe a young woman could be so cruel. So cold.”

“That sounds like a personal problem.” Tamsin shifted the baby to her other arm. She knew the townspeople talked about her, hurriedly exchanging whispers and angry words as they waited at the butcher’s stall for their paper-wrapped packages. Still, Tamsin knew the woman would pay. In the end, people always paid.

“I’d rather seek out a sprite.” The woman’s voice was ragged through her tears. “The river is only two days’ walk.”

Tamsin snorted. That was the trouble with ordinary folk. They loved magic, but they were frightfully flippant about the consequences. They’d trade a cow for a handful of magic seeds. They would offer up their voice to a mermaid in exchange for a smaller nose. They would seek out the trolls that lurked beneath bridges in the swampy Southlands, hoping to be granted a wish. But there was always a price for their impulsivity—the seeds bloomed flowers that sang incessantly, the new nose was always running, and trolls, who were notoriously indifferent to nuance, tended to misinterpret intention.

The only way to ensure that a magical request was balanced, legal, and properly interpreted was to barter with a witch. Since the Year of Darkness—a time still spoken of in hushed whispers despite the nearly thirty years that had passed—relations between witches and ordinary folk had been closely regulated by both the Coven and the queen to ensure the safety of the ordinary folk and the responsibility of the witch.

Tamsin, despite having been expelled from the academy and banished from the witches’ land, Within, was not exempt from that responsibility. If anything, her isolation and her curse were added reminders that magic had consequences. It was a blessing that Tamsin was allowed to practice village magic. It was a mercy that she was even alive.

Of course, it rarely felt like a mercy. But that was probably because the Coven had made it so she could not feel at all.

“If you want to take your chances with a sprite, by all means, let one give your baby gills,” Tamsin said with a shrug, offering the woman the bundle in her arms. “But you and I both know your child won’t make it through the night.”

The woman deflated. She shook her head, then grabbed for the girl, who had toddled forward toward Tamsin’s table of knickknacks. The girl squirmed in protest. Tamsin cooed emptily at the unmoving baby.

The mother held her daughter firmly by the shoulders, staring tenderly at the little girl’s pinched, reddening face. Then the woman’s head snapped up. “Take my love for my husband.” Her eyes were wild, focused on something far away. “Please.”

Tamsin sighed, long and loud. People always tried to exchange romantic love for unconditional love, as though the two were interchangeable. But there was a significant difference. Conditional love was fickle. Often it fizzled and stalled, burning out so quickly that Tamsin hardly got more than a handful of uses from it. A mother’s love for her child, however, could last her several months if she rationed it carefully.

A child for a child. Tamsin thought it fair. But the woman felt otherwise. Her eyes were as fiery as the flames roaring in Tamsin’s hearth.

“Take it,” she said, advancing toward the witch, who was still cradling the child. “I give it to you willingly. Please”—her eyes blazed—“I beg of you. Take it. You must.”

Tamsin took an inadvertent step backward, nearly tripping over an empty basket. She recovered quickly, both her balance and her impassive expression.

“How long have you been married?”

The woman furrowed her brow in confusion. “Three winters.”

Tamsin considered it. Longer relationships often bore more fruitful love, but there was always a chance that the love between the couple had begun to sour or turn stale. Shorter relationships were riskier: They carried less romantic weight but could provide a similar bounty if the couple in question radiated passion.

The woman had been married for three years. She had two children and, if Tamsin wasn’t mistaken, another on the way. Clearly, it wasn’t for lack of trying.

Sensing a lapse in her mother’s attention, the little girl squirmed out of her grip and wrapped a tiny, plump hand around the quartz sitting on the table’s edge. Her eyes were wide with wonder as she cradled it in her palm.

The woman lunged forward, flinging the quartz from her daughter’s hand without touching it herself. It clattered to the floor near the stone hearth. The little girl let out a loud wail and scampered toward the crystal. But the mother was quicker, scooping her daughter into her arms. The girl continued to struggle, pounding at her mother with her tiny fists.

Tamsin felt a rush of appreciation for the little girl’s resolve. She reminded Tamsin of Marlena. Headstrong. Curious. Impossible to wrangle. The memory made her blood run even colder. Carved a desperate, aching hole in her useless heart.

“Fine,” she snapped, cursing herself inwardly the moment the word slipped through her lips. It appeared that her most recent store of love—a crush on the smith’s apprentice given in exchange for a spool of unbreakable thread—hadn’t run out the way she’d thought. She’d had one small ounce of compassion left in her. And, thanks to her ever-present guilt, she’d wasted it on a squalling two-year-old.

Whatever Tamsin had felt, it was gone as quickly as it had appeared. She watched impassively as the woman fell to her knees, sobbing no longer with anguish but with relief.

“Get up,” Tamsin said, her voice sharp.

The woman did.

Tamsin gestured for the woman to come closer. The mother took several hesitant steps, eyes wide like a startled deer. Tamsin covered the remaining distance quickly and placed her hand over the woman’s heart. The mother squirmed beneath her touch.

“Think of him,” Tamsin commanded.

The woman closed her eyes. Tamsin kept her gaze steady on the woman’s face. The palm of her hand grew warm. The woman’s love ran up Tamsin’s arm and into her bloodstream. The room began to brighten—the greens of her freshly gathered herbs were bright and waxy; their sharp scents wafted through the afternoon air, tickling the inside of her nose. Tamsin’s spirits rose as she reveled in the warmth spreading through her body, into her bones.

She had already started to waste it.

Her hand still on the woman, Tamsin focused on the love running through her, sending it to her center. She ushered it carefully to her chest, where her heart sat empty, good for nothing but keeping a steady beat.

Tamsin tucked the love into the left-hand corner of her rib cage, trying to corral it as best she could—although, of course, love could never truly be controlled. It was like trying to trap flies in a birdcage. All Tamsin could do was try to keep her wits about her and stay as levelheaded as possible so that the love would only be used when she chose to access it. She could not afford another slip of compassion. Not when customers were already so few and far between.

When she was quite certain everything was properly secured, Tamsin removed her hand. The room darkened, the scent faded, and the chill returned, settling into her body familiarly, like a cat in a favorite chair. The woman had gone ashen and expressionless.

“Now, then.” Tamsin returned her attention to the child in her arms. Seven times she swept a finger from his tiny forehead down the bridge of his nose, over his lips, and past his chin. Magic flowed from her finger, spreading slowly through the tiny life she cradled. The cottage was silent, save for Tamsin’s whispers and the crackling of the flames.

Then the bundle twitched.

Tamsin removed her finger, breaking the stream of magic. The baby’s skin was no longer gray but the soft brown of his mother’s. Two tiny pink spots spread across his cheeks. He opened his mouth, letting loose a screech so loud Tamsin’s head began to scream in response.

The woman let go of her struggling daughter and rushed forward, all but ripping her son from Tamsin’s arms. She cradled her screaming baby close, tears falling from her face.

Tamsin had quite preferred the child when he was quiet, but the mother seemed pleased. She thanked Tamsin in a babbling, wet whirlwind before taking her daughter by the hand and rushing from the hut.

Tamsin slumped into a hard-backed wooden chair and eased off her leather boots. She rolled out her ankles, wincing as they cracked. Her head was pounding, and her littlest toe ached.

It was, Tamsin knew, a truly mild price to pay for the magic she had just performed. Most witches her age would have been bedridden for days after untangling and extracting such a severe sickness from another person’s body. Of course, most witches her age were still at the academy, where they weren’t allowed to perform such a spell at all.

No other young witch was as powerful as Tamsin, but then, no other witch had been cursed and banished from the world Within, either. No other witch had spent her seventeenth birthday cooing emptily over a baby, trying not to shrink beneath the hateful eyes of his mother.

For it was her birthday, the first day of what was supposed to be the most important year of her life. Seventeen was the age witches graduated from the academy. It marked the year they could decide their destiny—to stay Within and serve the Coven, or to go beyond the Wood and live among the ordinary folk.

Tamsin had always dreaded her seventeenth birthday, because while she had only ever wanted to stay Within, her sister, Marlena, had only ever wanted to leave.

In the end, good-bye had come much sooner than she’d expected.

Once Tamsin had been relegated to Ladaugh, a provincial farming town in the ordinary world beyond the Wood, seventeen became nothing more than a number. Now it was merely a reminder that she had been on her own for nearly five years and a disgrace for even longer.

Tamsin smacked her palm against the smooth wooden table. She hated herself for her power. No good had ever come from it. If she weren’t so desperate to take a break from the swirling gloom in her head and the empt...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Map of The Queendom of Carrow

- Chapter One: Tamsin

- Chapter Two: Wren

- Chapter Three: Tamsin

- Chapter Four: Wren

- Chapter Five: Tamsin

- Chapter Six: Wren

- Chapter Seven: Tamsin

- Chapter Eight: Wren

- Chapter Nine: Tamsin

- Chapter Ten: Wren

- Chapter Eleven: Tamsin

- Chapter Twelve: Wren

- Chapter Thirteen: Tamsin

- Chapter Fourteen: Wren

- Chapter Fifteen: Tamsin

- Chapter Sixteen: Wren

- Chapter Seventeen: Tamsin

- Chapter Eighteen: Wren

- Chapter Nineteen: Tamsin

- Chapter Twenty: Wren

- Chapter Twenty-One: Tamsin

- Chapter Twenty-Two: Wren

- Chapter Twenty-Three: Tamsin

- Chapter Twenty-Four: Wren

- Chapter Twenty-Five: Tamsin

- Chapter Twenty-Six: Wren

- Chapter Twenty-Seven: Tamsin

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright