eBook - ePub

Your Science Classroom

Becoming an Elementary / Middle School Science Teacher

Marion J. Goldston, Laura M. Downey

This is a test

Share book

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Your Science Classroom

Becoming an Elementary / Middle School Science Teacher

Marion J. Goldston, Laura M. Downey

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Designed around a practical "practice-what-you-teach" approach to methods instruction, Your Science Classroom: Becoming an Elementary / Middle School Science Teacher is based on current constructivist philosophy, organized around 5E inquiry, and guided by the National Science Education Teaching Standards. Written in a reader-friendly style, the book prepares instructors to teach science in ways that foster positive attitudes, engagement, and meaningful science learning for themselves and their students.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Your Science Classroom an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Your Science Classroom by Marion J. Goldston, Laura M. Downey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Elementary Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I the Nature of Science

Chapter 1 I Know What Science Is!: It's An Experiment!

Learning Objectives

After reading Chapter 1, students will be able to

- Recognize and describe the basic tenets of science and scientific knowledge

- Identify the National Science Education Standards (NSES) associated with inquiry and the nature of science

- Describe science as a body of knowledge, processes, and a way of knowing

Nses Teaching Standards Addressed in Chapter 1

Standard B: Teachers of science guide and facilitate learning.

In doing this, teachers

- focus and support inquiries while interacting with students;

- orchestrate discourse among students about scientific ideas; and

- encourage and model the skills of scientific inquiry, as well as the curiosity, openness to new ideas and data, and skepticism that characterize science.

Standard D: Teachers of science design and manage learning environments that provide students with the time, space, and resources needed for learning science. In doing this, teachers

- structure the time available so that students are able to engage in extended investigation;

- create a setting for student work that is flexible and supportive of science inquiry;

- make the available science tools, materials, media, and technological resources accessible to students; and

- identify and use resources outside of school.

Source: Reprinted with permission from the National Science Education Standards, copyright 1996, by the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

Introduction

This book is for you, the K–8 science teacher. It is important that you understand the approach you will find here is different from other science methods textbooks. First, you will find that each chapter is organized around an inquiry approach supported by the National Science Education Standards (National Research Council [NRC], 1996) and advocated as an effective way to teach K–8 science through inquiry—an approach discussed in more detail in Chapter 8. The organizing framework for each chapter is an inquiry approach known as the 5E instructional model. The five “E's” of this approach refer to a sequence of phases: Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, and Evaluate. In brief, the engage phase motivates students and seeks to uncover students’ prior ideas of the concept to be taught. The explore phase is associated with student activities, and the explain phase follows with teachers’ questioning students by drawing on the science activities conducted in the classroom. The elaborate phase requires a new application of the concepts learned, and the evaluate phase is an evaluation of student learning. Because the 5E model is highly student centered, each chapter embeds activities within each of the phases that are designed for you to examine or perform. In essence, the chapters are designed to be interactive, while bringing to life the 5E model for teaching K–8 science. Our vision, therefore, begins with you, and our goal for you is to broaden your understandings of science, scientists, and science teaching using the 5E model. As such, we will introduce ideas, concepts, and processes that you need to know and understand before we ask you to apply and use them with your students in your science classroom.

So, let the journey begin.

When you think of science, what do you think about? Do you think of your science experiences in school? Do you think of the science books, vocabulary, and concepts that you had to learn in school? Do you think of a science project you did in elementary, middle, or high school? Do you think about science experiences outside of school? We know that we ask a lot of questions, but your understanding of science as a field of study with its own characteristics is important. What you think and know about science will be reflected in what and how you teach shaping the K–8 science teacher you will become. In this chapter, we will explore those traits that define science and scientific knowledge as a discipline that is somewhat different from other disciplines. You also will examine how science and scientific knowledge are viewed in light of the NSES (NRC, 1996) for envisioning effective science teaching and learning.

Let's start with you. Before you read further, take a few minutes to take a paper and pencil and draw a scientist or what you think a scientist might look like.

After you complete your drawing, share it with one of your classmates or ask a friend to draw a scientist and take a look at each other's drawing. Reflect on what details you and your peers have included or omitted. Write statements about what the drawing or drawings tell you about the individuals’ images of a scientist (i.e., mad scientist). After having explored your image of a scientist, reflect further. What is the work of scientists really like? What would you say if one of your students asked, “What is science?” or “How is science done?”

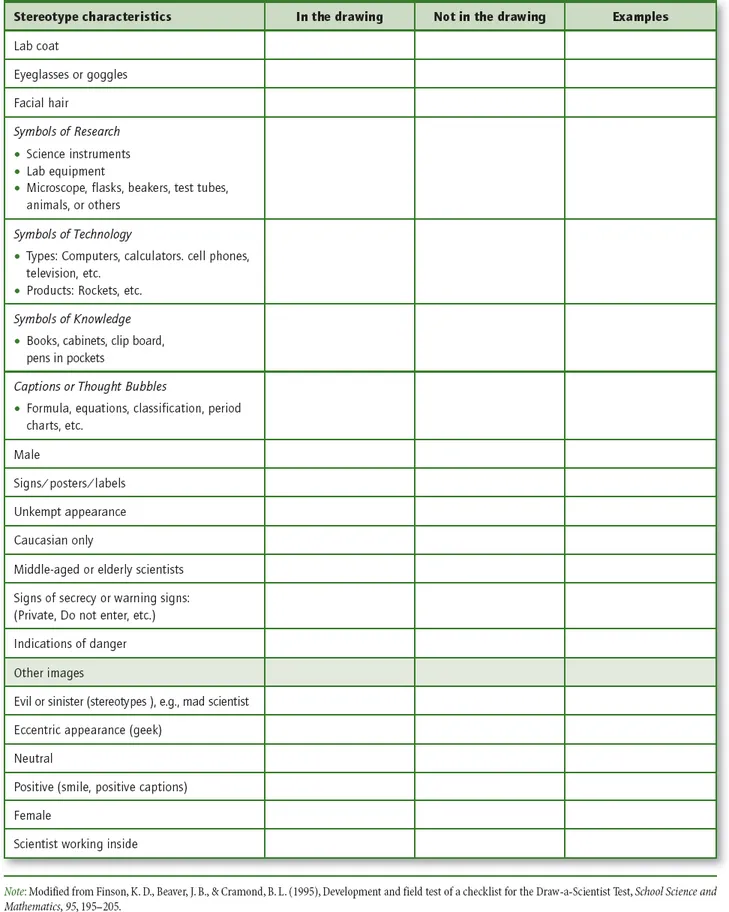

Now that you have completed this activity, examine your drawing using the “Draw-a-Scientist Test” (DAST) checklist (Table 1.1) to gain insights into views of scientists and the stereotypical characteristics that individuals commonly imagine (Finson, 2002, 2003; Finson, Beaver, & Cramond, 1995). Keep these ideas in mind as you draw on your inner scientist in the following activity.

Note: Modified from Finson, K. D., Beaver, J. B., & Cramond, B. L. (1995), Development and field test of a checklist for the Draw-a-Scientist Test, School Science and Mathematics, 95, 195–205.

Engage

Making Observations and Inferences with a Fossil

Now, think for a moment about a core skill needed to conduct scientific investigations. Did the word “observation” come to mind? It's a word you've heard many times before, but how would you define it? An observation is any information gathered through your senses or with instruments to extend your senses. Eighty-five percent of the observations made by sighted people come from one sensory organ, our eyes. However, when teaching students about the process of observation, it is important to stress that the best observations use more than one sensory organ to collect data. Be aware that when students make observations they also make explanations, generalizations, or draw conclusions based on their observations and experiences. These general statements are called inferences, and they may or may not be correct. Inferences are explanations, generalizations, or conclusions a person makes based on observations and experiences. As a science teacher, it is important to recognize the difference between the skills of observation and inference when teaching students. Consider the following sentence: “I ran into the kitchen and saw Mel standing by the table holding a cloth dripping water.” To get you started, here is one observation: There was a table. Another observation is Mel was standing. An inference is an explanation that may or may not be correct. An inference you might make is that Mel is a male. Mel may or may not be a male. We do not know. Another inference is that Mel spilled water and was cleaning it up. So, look at the sentence again. What other observations and inferences can you make?

Teacher's Desk Tip: Addressing Diversity in Your Classroom

Consider adaptations for students with diverse needs. How would you adapt the fossil activity for a child who is visually impaired? Perhaps you could make clay model of the bones, or use actual fossils. Can you think of other adaptations?

Figure 1.1 Fossil Bone

Making observations and inferences are fundamental skills in science; let's put those skills to work. Imagine you were fortunate enough that your paleontology professor, who needed a few extra assistants, offered you an opportunity to go on a dig to Morocco over the summer. During that trip, you found a most unusual fossil. You photographed the fossil and, with the help of your peers, you seek to find out what you've found. Now, look at the fossil you found (see Figure 1.1).

Make a concept web (graphic organizer that can be used to organize ideas, thoughts, concepts, and skills around a central topic or theme) or a list of statements about what you know about fossils. In making the web, consider the following questions: What are fossils? How do they form? Where do we find them? What process(es) create fossils? How do you think scientists reconstruct organisms from fossils? What tools do scientists use to reconstruct organisms from fossils? Next, look at the fossil pictured in Figure 1.1 and create a list of observations about it. What inferences can you make about the fossil? Describe the relationship between your observations and your inferences. Explain.

Explore

Digging into the Nature of Science

Your exciting discovery has led you to pursue a dual degree in education and paleontology. You spend your summers at various archaeological digs, but that fossil you found remains on your mind. You're driven to know more. An opportunity to join a funded expedition back to Morocco and additional sites where similar fossils have been found becomes available through the National Observation System grant program. Fortunately, the university's scientific team was awarded a large grant and can assemble research teams to gather more information about your fossil find. You remember how excited your science m...