eBook - ePub

Stress and Health

Biological and Psychological Interactions

William R. Lovallo

This is a test

Share book

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stress and Health

Biological and Psychological Interactions

William R. Lovallo

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Stress and Health: Biological and Psychological Interactions is a brief and accessible examination of psychological stress and its psychophysiological relationships with cognition, emotions, brain functions, and the peripheral mechanisms by which the body is regulated. Updated throughout, the Third Edition covers two new and significant areas of emerging research: how our early life experiences alter key stress responsive systems at the level of gene expression; and what large, normal, and small stress responses may mean for our overall health and well-being.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Stress and Health an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Stress and Health by William R. Lovallo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Neurociencia cognitiva y neuropsicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Psychosocial Models of Health and Disease

Chapter objectives

- Disease processes should be seen as dynamic interactions between the causative agent and the affected organism.

- The disease and its treatment are embedded in a hierarchy of systemic controls. That is, lower levels of the system are in two-way interaction with higher levels in the system, and each level integrates and regulates the levels below it.

- The hierarchy of causal influences ultimately includes complex behaviors such as the thoughts and emotions of the affected person and the socioculturally determined environment in which that person lives.

- Disease and its cure exist in the physical and mental workings of the body, and thoughts and emotions play a significant role.

What is this book about? It is a short review of how our behaviors, especially ideas and associated emotions, come to have power over our bodies. It is an attempt to create a model of the psychological stress response in relation to its biological consequences and its implications for health. In the following discussion, I hope to provide some useful insights into how psychological theory can contribute to our view of medicine.

In 1928, the American physiologist Walter Cannon was addressing the Massachusetts Medical Society on the subject of emotions and disease. He noted that

a wife, who was free from any cardiac disorder, saw her husband walking arm in arm with a strange woman and acting in such a way as to rouse jealousy and suspicion. Profoundly stirred by the incident, the wife hastened home and remained there several days. She then began to fear going out lest she might meet her husband with her rival. After days of wretchedness, she was persuaded by a friend to venture forth, “probably in a state of abject terror,” . . . but she had not gone far when she ran back to her home. Then she noted that her heart was thumping hard, that she had a sense of oppression in her chest and a choking sensation. Later attempts to go outdoors produced the same alarming symptoms. She began to feel that she might die on the street if she went out. There was no organic disease of the heart, and yet slight effort as she moved from her home brought on acute distress (Cannon, 1928).

It is always impressive to see how the impact of a psychologically meaningful event can change a person’s physical state. Examples like this lead us to ask “How can an idea change the body?”

This book is concerned with mental activity and behavioral processes and their relationships to states of health and disease. We specifically take up the question of psychological stress and describe how mental activity can produce negative effects on the body, perhaps leading to disease or even death. The book will present research indicating how the effects of psychological stress can be buffered by early experiences, leaving the individual better able to withstand stresses and strains of life. These positive examples are few in number, and they suggest that much more is known about vulnerability to stress than about hardiness or resilience.

I mentioned that this book was about mental and behavioral processes. When I say behavior, I mean not only moving and talking but also the neural processes giving rise to thoughts and emotions. Ideas about the relationship between the mind and the body have been debated since the ancient Greeks. In fact, the mind-body problem is one of the fundamental philosophical and scientific issues in human knowledge. The ways of combining our thinking about behavior and mental life into our thinking about medicine are essential to developing a truly behavioral medicine.

Although the example above is true to life and perfectly understandable as a reaction, we realize that we have little understanding of how this woman’s seeing her husband with his girlfriend led to such extreme fear and to her physical symptoms. Since 1928, researchers have become increasingly familiar with the mechanisms of the brain and how these control the rest of the body. Similarly, psychology has increased our knowledge about how we learn, think, and take in the world. Still, studies of the workings of the body and the processes of the mind tend to exist in separate departments at our universities and in separate compartments of our thinking. This division hinders understanding our woman patient and the relationships between her experience, emotions, and her physical state. In considering behavioral influences in health and disease, we need to have a way of thinking about how words can affect the body. We understand how bacteria and viruses can invade our body and how heart disease develops in the arteries of the heart, but we are not yet fully comfortable with the idea that psychological processes such as emotions and personality characteristics can influence these same disease processes.

We know, or at least most of us believe, that we can’t use our minds directly to influence outside objects. We can’t levitate things. We can’t transport ourselves to another place by means of thought. And yet, the example demonstrates that the mind influences the body, sometimes in dramatic ways. Before we discuss specific psychological contributions to stress responses in later chapters, we should give thought to a more general conceptual model of how mental processes can affect the health of the body, interacting with processes of health and disease. This brief consideration will allow us to place the topic of psychological stress into a behavioral medicine framework. In addition, it helps us gain an appreciation for how the behavioral medicine approach may complement and enrich a more traditional medical model.

We will start here by analyzing the infectious disease process using a very restricted biomedical model. We will see how this model can be usefully expanded to include the behaviors of the patient. A second example will describe how behavioral medicine can be useful in coming to understand the ways in which placebo effects operate. Finally, we will consider how a behavioral medicine approach is especially helpful in conceptualizing cause and treatment in complex diseases such as coronary artery disease.

The Standard Biomedical Model and New Approaches to Medicine

We begin here with a short comment on the enormous influence of the writings of the great French philosopher René Descartes, who argued that we could study the workings of the body as if we were studying a machine that we had seen for the first time and that to do so, we did not need to inquire into the workings of the soul, as he called the mind, which he saw as the seat of our consciousness (Descartes, 1637/1956). Although Descartes was most likely finding a path to discussing physiology without offending officials of the Catholic Church, he is credited with the dubious distinction of putting a dualistic stamp on our thinking about ourselves. This stamp made it easier to talk about the mechanisms of the body while ignoring the processes we now associate with thoughts and emotions. Indeed, he put these into fundamentally separate categories that were not compatible with each other.

In line with the Cartesian idea, the standard biomedical model goes like this: Disease is a linearly causal process, “a condition of the living animal . . . or one of its parts that impairs the performance of a vital function.” In other words, disease is disorder in an otherwise smooth-running machine. The cure is to disrupt the causative agent at the physical level to help the machine repair itself, restore order, and regain normal function. Finally, in the strong form of this model, following our Western tradition, the workings of the mind are not relevant to the disease or its cure.

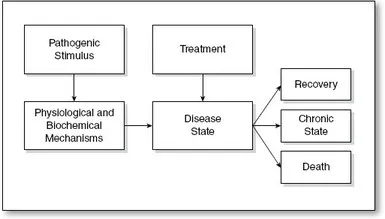

Figure 1.1 is a conceptual diagram of this strong form of the biomedical model. The diagram illustrates a normally functioning person being acted on by some pathogenic stimulus such as an infection, a cancer, or coronary heart disease. The mode of therapy is a direct physical intervention to restore the person’s healthy, well-ordered state. Such therapies may be the administration of an antibiotic to cure a bacterial infection, the application of chemotherapy for a cancer, or coronary bypass grafts for coronary heart disease. All of these treatments have known restorative, if not curative, properties. Their application in individual cases results in one of the three outcomes on the right. We hope that the patient gets better. However, other outcomes also occur, including continued illness or even death.

Figure 1.1 Traditional medical model of the disease process. The disease process and the treatment are shown acting on a passive organism, and the treatment and disease do not interact. This depicts a restrictive view of the traditional medical model.

A key feature of this model is that the cure works with or without the knowledge or assistance of the patient. The cure is purely physical and not affected by the thoughts or emotional state of the person being treated. This traditional model has the following characteristics:

- The model has one-way causation. The pathogen acts on the host and not the other way around.

- The disease is a physiological process, and treatment operates on the physiology of the person to alter the disease state.

- Therefore, the model is nonhierarchical, meaning that different levels of complexity in the system, particularly higher nervous system controls related to thoughts and emotions, do not interact with each other.

- As a result, the model is dualistic. The mental status of the person is incidental to the cause of the disease and its cure. The mind and the body exist in different realms in this framework, and there is no strong basis for considering how they might work together for the person’s well-being.

In considering the contrasting features of the biomedical model and the behavioral medicine model presented here, the following points should be kept in mind:

- The traditional biomedical model has proven to be very effective at treating disease. When speaking of the shortcomings of the model, I simply mean that it is limited because it has no way to incorporate the knowledge that thoughts and emotions can enhance development of diseases or promote their cures.

- Although we may consider emotions to be important in the health equation, and while we talk about the power of thoughts, we should recognize that these rarely are, if ever, the sole cause of disease. Instead, we think that such mental processes may aggravate, alleviate, and otherwise modify existing disease processes.

- We are only just beginning to understand how interactions between psychological processes and disease pathophysiology may occur. The information in this chapter is primarily a formal description of how such interactions may operate. Later chapters will deal with these interactions in more mechanistic fashion.

- The possibility that behavioral influences may alter disease processes should be approached with the same scientific caution used in understanding diseases and cures within the standard biomedical model.

This description of the traditional biomedical model and ways that it can be expanded is presented deliberately in stark terms. This strong distinction allows us to sharpen the contrast between approaches and to illustrate the potential contributions of a behavioral medicine. As individuals, doctors understand that the mind affects the body. Practicing physicians are well aware of the power of thoughts and emotions to affect health, and that worry, grief, and anxiety are obstacles to effective treatment. The problem for the physician is that the standard model by its nature does not provide a path for putting this intuitive knowledge into practice or for turning these mind-body relationships to the patient’s advantage. Knowing that the mental state of the patient may affect the disease and response to treatment therefore becomes part of the art, rather than the science, of medicine even in the hands of an insightful and empathetic practitioner.

Important areas of medical practice, such as family medicine, have a strong commitment to a biopsychosocial model of health. That is, they recognize the importance of the doctor-patient relationship, and treatment acknowledges that physical health is affected by psychological processes and by social conditions. Here, the physician has a philosophical commitment to appreciating the impact of social and psychological causes in health and disease and to bringing this understanding into the clinic. Unfortunately, there is little in standard medical training that provides skills and knowledge in applying a biopsychosocial model.

The other side of this problem is that the emerging science of behavioral medicine is a promise yet to be fulfilled. There is a great deal of work to be done. Disciplines like psychology need to contribute to a base of theory and rigorously acquired knowledge that can lead to practical applications. This book will not solve the problem, but it will attempt to lay out what we know about the impact of psychological stress on the body, using an approach grounded in the neurosciences.

A Biobehavioral Model of Disease and Treatment

The model of disease outlined above is narrow. It restricts our view of the range of processes acting on our bodies, and this limits our thoughts about the causes and therapeutic interventions possible in a behavioral medicine. We can expand our view of the disease process by embedding our first model in one that includes the person’s learning history and sociocultural environment as shown in Figure 1.2.

This enlarged model of disease and treatment shows three important interactions between the person and the environment:

- The person’s psychosocial processes, meaning his or her thoughts, emotions, and spoken words, interact with the social and cultural environments. These informational interchanges, for example, information concerning the nature of the disease and its cure, can affect its outcome.

- The pathogen not only affects the person’s physiology, but the actions of the person’s immune system also alter the pathogen. This two-way interaction represents an exchange of information between host and pathogen, if we consider that each is learning something from the other.

- The treatment still acts to alter the disease state, as it did in the first example. However, the model includes interactions among the treatment, pathogen, and host, and the social environment and psychosocial functioning as processes that affect treatment outcome.

Figure 1.2 Expanded ...