eBook - ePub

Organizational Creativity

A Practical Guide for Innovators & Entrepreneurs

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organizational Creativity

A Practical Guide for Innovators & Entrepreneurs

About this book

Reignite your creative-thinking skills to produce innovative solutions

Organizational Creativity: A Practical Guide for Innovators and Entrepreneurs by Gerard J. Puccio, John F. Cabra, and Nathan Schwagler, is a compelling new text designed to transform the reader into a creative thinker and leader. Arguing that creativity is an essential skill that must be developed, the authors take a highly practical approach, providing strategies, tools, and cases to help readers hone their creative abilities. Whether students are preparing to become entrepreneurs or to work in an established firm, this text will help them survive and thrive in an era of innovation and change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organizational Creativity by Gerard J. Puccio,John F. Cabra,Nathan Schwagler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Decision Making. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I KnowingCreativity Knowledge to Support a 21st-Century Innovator

Chapter 1 Innovation WiredYou Evolved to Create

Learning Goals

After reading this chapter, you will be able to do the following:

- Use a scientifically based argument to defend the view that all humans are creative

- Explain the lessons that can be extracted from evolution and how these lessons translate into strategies for innovators and entrepreneurs

- Contrast two fundamentally different forms of creativity: eminent creativity and everyday creativity

- Appraise the degree to which you actively work to enhance your innate creativity through practice, passion, and play

- Formulate a plan for improving your creative thinking by using journaling and/or in-and-out note taking on a regular basis

Knowing—You Were Born to Be Creative

Creativity Lessons From Evolution

The question is not whether you are creative. You are! The better question is, am I living up to my creative potential? And, assuming there is always room for growth, a natural follow-up question is, in what ways might I be able to enhance my creativity? This opening chapter uses information extracted from science, biology, and anthropology to demonstrate that all humans with normally functioning brains are endowed with creative thinking and therefore possess the ability to create. Our species alone has the imagination and the dexterity to make complex tools and to produce new technology. Creative thinking is the competitive advantage of our species; thus, through evolution this competitive advantage has been selected for and developed through the millennia.1 You were born creative, and we contend that you can enhance your success as an innovator and entrepreneur if you tap into your innate creativity. To that end, we use lessons from evolution to present the first set of tips you can follow to extend the natural creative talent you already possess.

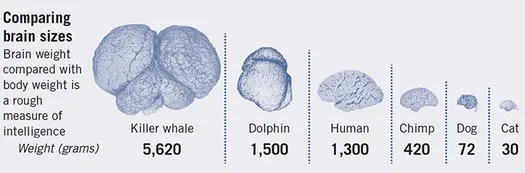

Let’s be honest about our species. When you compare humans to other animals with whom we share planet Earth, it is plain to see that humans are not the fastest, strongest, or biggest. Humans cannot fly away from danger nor hide underwater (at least not for very long). Even though the human body is not particularly well insulated from cold temperatures or designed to efficiently cool down in blistering heat, our species has found a way to expand around the globe and to inhabit a wide range of climatic conditions. How is this possible? To what quality can we attribute such adaptability and flexibility? If it is not strength and speed, nor other forms of physical prowess, could it be the size of our brains? It is not size alone, however, for humans cannot claim to have the largest brains; the prize for size belongs to elephants and some whales. What is unique about the human brain is its rare and valuable cognitive ability—creative thinking. Humans may not be fast, strong, or big, but humans can employ imagination in a way that leads to mental and behavioral flexibility that, through experimentation and evaluation, leads to novel solutions.2

It is likely that the mental ability to generate creative solutions was present in its nascent state in prehumans and then developed in ever-expansive ways from early humans through to the creative minds now found in modern humans. Although human evolution did not advance along a straight line, with competing branches often existing at the same time, evolutionary psychologists have concluded that developments in the size and structure of the human brain over time led to corresponding increases in the complexity of products generated by the evolving Homo species.3

In 1974 an unusually complete skeleton of a species that served as a forerunner to humans was found in Tanzania, Africa. The skeleton, nicknamed “Lucy,” had been preserved in sediment for more than 3.6 million years. Lucy and others from her species, called Australopithecus afarensis, were about the size of chimpanzees and walked upright. These diminutive creatures survived for about 700,000 years, from about 3.6 million years ago to about 2.9 million years ago, an impressive longevity for an animal so small and fragile. Imagine the frightening conditions this prehuman species must have faced, an easy meal for any number of four-legged animals and birds of prey. It is likely that the mental conditions that eventually blossomed into the highly functioning creative brains humans enjoy today were beginning to form in Lucy’s mind. According to science writer Douglas Palmer, Lucy and her tribe lacked sharp teeth, claws, and speed; however, they made up for these physical deficiencies with cooperation, communication, and creative intelligence—exemplified by the use of sticks and stones as weapons.4

Figure 1.1

Source: Bellville/MCT/Newscom

There are animals today that use objects found in nature as tools. Sea otters, for instance, use rocks to crack open crabs, mussels, and oysters. Chimpanzees strip the leaves off small branches to fish for termites and ants. Early humans carried out similar forms of practical problem solving that eventually led to what anthropologists refer to as the creative explosion in human civilization about 50,000 years ago. At this critical breakpoint, humans moved from applying imagination to solving practical problems, like finding food to eat, to applying imagination in all sorts of interesting ways, such as burial rituals and art.

Let’s look at some examples of the tools created through the imaginations of the earliest human species. The first tool made by humans is called the flaked tool (approximately 2.6 million years ago). With a brain capacity of about 50% of modern humans’, the Homo habilis broke fine-grained rocks into sharp-edged flakes to split open fruit and nuts. The process of manufacturing this tool—and we do mean manufacturing, in that these early humans had to first locate the materials and then fashion these tools from them—required a degree of higher-level thinking. The flaked tool lasted about 1 million years, then like all creative ideas, it was surpassed by a new and improved idea—the hand ax.

Homo ergaster, with a brain 75% the size of that of modern humans, is credited with the development of a symmetrically shaped tool that was easier to hold while striking objects (approximately 1.76 million years ago). The pear-shaped design had a sharp point and edges on one side and a blunt end, held in the palm of the hand, on the other. Some experts argue that this more complicated, all-purpose tool is evidence of increasingly more complex mental functions in humans. Geneticist Morriss-Kay, for example, suggests that the multistep manufacturing process associated with the hand ax illustrates the emergence of mental operations unique to the human species, such as being able to see “in the mind’s eye.”5

The life cycle of the hand ax endured over 1 million years. Although we are endowed with great imagination, it may be difficult to imagine any product created today that will still be in use in half the life cycle of the hand ax, that is, 500,000 years from now. In today’s world, manufactured products go through fundamental redesign every 5 to 10 years, whereas technologically based products experience significant redesign every 3 to 6 months.6 How long do you think it will be before you consider that phone in your pocket so outmoded that an upgrade becomes necessary? Contrasting the life cycle of these early creative products to those of today highlights the increase in the pace of change as driven by human creativity.

With each successive human species came more sophisticated tools. And with Homo sapiens, the modern human being, the expanding use of imagination eventually led to a tipping point referred to as the creative explosion, that is, a dramatic increase in the complexity and diversity of human artifacts dating back to about 50,000 years ago. In a relatively short span of time, 10,000 to 20,000 years, the human imagination began to produce art (e.g., cave paintings and figurines), sew clothing, create musical instruments, construct purpose-built shelters, and develop elaborate social rituals such as those associated with burial.

Given that the brain reached its present volume with the emergence of Homo sapiens roughly 200,000 years ago, it might occur to you that the creative explosion lagged far behind the emergence of the modern human—a gap of more than 100,000 years. Why was there such a lag between the appearance of the fully modern human and the diverse application of creativity? Following are some insightful explanations of human evolution that connect to our contemporary understanding of creativity and underscore, we believe, how humans have been wired to be creative.

Development of the Fully Creative Brain: Use Your Whole Brain

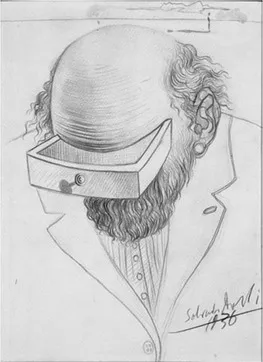

Some psychologists, scholars, and archeologists believe that whereas the thinking skills associated with creativity were present in early Homo sapiens, these skills continued to be refined as the modern human evolved. It took time for modern humans to learn to direct their thinking. Humans are self-aware and can think about their own thinking. For the creative process, it is especially important that humans manage to balance and move back and forth between two basic forms of thinking—divergent and convergent thinking.7 Divergent thinking is an exploratory form of thinking, looking for possibilities, identifying in our mind’s eye what might be, generating novel responses, and making associations. For example, the Dalí sketch included in this chapter reflects this artist’s ability to see in his mind’s eye a strange new possibility. Though drawn in 1936 this sketch looks a lot like augmented-reality goggles used by today’s gamers. Convergent thinking is testing, evaluating, refining possibilities, and exploring ways to make our novel ideas valuable. To create, humans need to be able to engage in both forms of thinking and to direct their thinking so they apply these skills effectively. Cognitive scientist Liane Gabora argues it is exactly this process of switching between these two forms of thought that makes up the fundamental approach used by successful creative people today:

When tackling a problem, they first let their minds wander, allowing one memory or thought to spontaneously conjure up another. This free association encourages analogies and gives rise to thoughts that break out of the box. Then, as these individuals settle on a vague idea for a solution, they switch to a more analytic mode of thought.8

Another significant shift in thinking believed to have contributed to the creative explosion is an ability called cognitive fluidity.9 It has been argued that before 50,000 years ago human thinking tended to be domain specific; that is, our thoughts were isolated to specific areas of knowledge—silos, if you will—that did not interact with each other. For example, Steven Mithen, a professor of archeology, describes three fundamental domains or areas of intelligence that were mastered by Homo sapiens and likely Neanderthals as well.10 These were social intelligence, natural intelligence, and technical intelligence. Domain-specific thinking is a form of vertical thinking in which a person builds up knowledge in isolated areas. By contrast, cognitive fluidity is a form of flexible thinking in which a person is able to develop new insights and ideas by cross-fertilizing thoughts from different domains.

Salvador Dalí, Freudian Portrait of a Bureaucrat, 1936 pencil on paper, image: 10 5/8 in × 7 3/4 in.

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2017

© Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc.

This ability to connect ideas across areas of knowledge is crucial to the creative process and helps to drive innovation. The way termites build their mounds, which are the tallest structures on Earth (when comparing the builders’ size to the size of the building), inspired an African architect who built highly efficient energy buildings. Ships’ propellers provided the solution for powering heavier-than-air flying machines. Facebook was inspired, in part, by the idea of a collegiate yearbook. Without cognitive fluidity, our creative thinking, problem-solving, and innovation efforts would be severely limited. Steve Jobs seemed to be abundantly aware of how the ability to cross-fertilize thoughts contributes to innovative success. As he observed, “I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians and poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world.”11

It took time for the human brain to develop the capacities to effectively engage in divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and cognitive fluidity. The good news is that, thanks to your ancestors, you are endowed with these same abilities, and through this book you will learn to take advantage of these innate thinking skills.

Emergence of Pretend Play: Be Childlike

Some scholars argue that cognitive abilities alone were not sufficient to cause the widespread application of our creative potential. It has been suggested that humans also had to develop a creative attitude to maximize the ever-increasing horsepower of their brains. Let’s look at an analogy: Two drivers may have equally powerful engines in their cars, but the one who has the willingness to explore the full power of that engine is likely to win in a head-to-head race. By contrast, the risk-averse driver is likely to be cautious, thereby underusing the full horsepower at his or her disposal.

In a similar way, our brains need an e...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- IntroductionPurpose and Design of This Book

- About the Authors

- Part I KnowingCreativity Knowledge to Support a 21st-Century Innovator

- Chapter 1 Innovation WiredYou Evolved to Create

- Chapter 2 How to Survive and Thrive in an Era of Innovation and Change

- Chapter 3 What We Know About Creativity

- Chapter 4 The Practical Benefits of CreativityBecoming an Innovation Asset

- Part II DoingProven Practices for 21st-Century Innovators

- Chapter 5 ThinkHow to Improve Your Fundamental Capacity to Think in Creative Ways

- Chapter 6 UnderstandThe Power of Observation and the Importance of Problem Definition

- Chapter 7 IdeateWays to Visualize and Generate Breakthrough Ideas

- Chapter 8 ExperimentStrategies to Develop and Validate the Best Solutions

- Chapter 9 ImplementGaining Buy-In and Driving Change

- Part III BeingWays to Sustain Yourself as a 21st-Century Innovator

- Chapter 10 The Emotionally Intelligent Leader

- Chapter 11 Sustaining Your CreativityLearning to Defy and Transform the Crowd

- Index