eBook - ePub

Research Methods in Applied Behavior Analysis

Jon S. Bailey, Mary R. Burch

This is a test

Share book

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Research Methods in Applied Behavior Analysis

Jon S. Bailey, Mary R. Burch

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This very practical, how-to text provides the beginning researcher with the basics of applied behavior analysis research methods. In 10 logical steps, this text covers all of the elements of single-subject research design and it provides practical information for designing, implementing, and evaluating studies. Using a pocketbook format, the authors provide novice researcher with a "steps-for-success" approach that is brief, to-the-point, and clearly delineated.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Research Methods in Applied Behavior Analysis an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Research Methods in Applied Behavior Analysis by Jon S. Bailey, Mary R. Burch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Ricerche e metodologie nella psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART | |

I |

WHAT IS APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS RESEARCH?

MAIN TOPICS

The Operant Research Model

Important Methodological Milestones

Measurement of Significant Behavior

Science and Clinical Success

A Paradigm Shift

The Dimensions of Applied Behavior Analysis

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

We first consider the operant research model of behavior and review observation and measurement procedures from a historic perspective. Next, we review the seven dimensions of applied behavior analysis. After studying this chapter, you should be able to

The field of applied behavior analysis has attracted a great deal of attention in recent years as the promise of an effective technology based on the products of an experimental analysis of behavior (Morgan & Morgan, 2001; Skinner, 1974) has begun to emerge. The contributions of the field are well documented in several journals now specifically devoted to the topic and in numerous excellent texts and collections of readings (see the suggested list of readings at the end of Part I). This extensive literature describes the important contributions that have been made in mental retardation, rehabilitation, delinquency, mental health, counseling, education, business and industry, and many other fields. It represents the development of procedures for behavior change arising from the experimental analysis of behavior with lower organisms.

Applied behavior analysis has attracted many enthusiastic participants, in part due to a kind of deceptive simplicity. Socially significant target behaviors are identified, an intervention is devised and put in place, and the resulting data show convincingly that it was effective. This apparent simplicity of the methodology may actually be a function of a limitation on journal space that prevents researchers and authors from fully describing the extensive efforts necessary to accomplish the behavioral changes that were achieved. Research articles almost never describe how a researcher came up with the original idea, nor do they trace the modifications in thinking that occurred through stimulating brainstorming sessions, sharing data with colleagues over coffee, or the pure dumb luck of being in the right place at the right time. Published articles rarely detail how the researchers happened to locate the particular environment where they work, gained the confidence of the established authority, and finally obtained permission to carry out their study. The specific details involved in the moment-to-moment conduct of the research once it is under way are simply never discussed in the text of an article. Such statements as “five preschool children were chosen” or “the study was carried out in three nursing homes” simply do not properly describe the extensive planning, intensive strategizing, and diplomatic behavior required from the applied researcher. This public abridged version is driven by the cost of journal space but grossly misrepresents the sustained effort and finely tuned skills researchers must acquire to conduct quality experimentation in applied settings.

Novice researchers, without the advantage of having apprenticed with established researchers, must often engage in extensive, frustrating, and wasteful trial-and-error activity. Applied behavioral research most often is exceedingly difficult to accomplish, often much more so than basic laboratory research where the subjects come in packing crates from a breeding farm, the measurement equipment is readily available, the experimental protocols are already established, and the research questions are derivative. The careful preplanning, eye for detail, compulsion for precision and consistency, and ample persistence required of all good researchers are obviously necessary. However, the creative, managerial, and administrative skills needed to conceptualize a unique applied problem and orchestrate the applied research are not obvious to the casual observer.

The present text is an effort to fill this void in the applied analyst’s repertoire. Over the years, it has become clear that there is a proven formula for successful research. A major goal of the present book is to describe that formula for aspiring researchers and practitioners in the form of helpful hints, specific steps, suggested guidelines, and rules of thumb that may be followed. The intent of this text is not to review the literature or prescribe treatment procedures but rather to give eager new researchers a set of guidelines by which they may carry out their own initial research and hopefully contribute to the science of behavior. Before we proceed, however, a brief review of some basic features of operant research and a few landmark studies that have contributed to our current methodology seems to be in order.

The Operant Research Model

The earliest applied research studies were patterned in many ways after the style of research developed by B. F. Skinner and his students (Ferster & Skinner, 1957; Skinner, 1938) as they worked with rats and pigeons. A fundamental feature of the methodology is the detailed analysis of the behavior of the individual organism. As was the case with the original laboratory studies, a small number of individual subjects (very often only one subject) were observed for extensive periods of time. In these early applied studies, the “free-operant,” ongoing behavior (frequently deviant in nature) of one or at most a handful of human subjects was measured during an initial baseline condition to determine the operant level of performance. Subsequently, some type of intervention procedure was systematically brought into contact with the target behavior, and the procedure’s effects were noted. At some later point in these original studies, the contingent procedures were withdrawn to provide further evidence of the procedure’s functional relationship to the target behavior.

Although this seemingly simple extrapolation of a kind of “case study” methodology would seem to be an easy extension, the task required some adjustments in experimental methods. New data-recording techniques had to be developed in the transition from laboratory to field research environment. Experimental subjects were humans with broader behavioral repertoires and larger environments. Manipulated consequences were more than food pellets and 2-second presentations of food hoppers. Target behaviors having social importance were usually not amenable to measurement with automated devices. Instead, human observers had to be extensively trained, and ways of ensuring the objectivity of measurement procedures were necessary. The reintroduction of the human observer into experimental analysis brought with it a host of logistical and methodological problems. These concerns were added to the difficulties associated with attempts to stabilize experimental environments in field settings. All of this contributed to the difficult early development of the emerging field of applied behavior analysis.

Important Methodological Milestones

Although it is often taken for granted, systematic observation procedures for collecting data on significant human responses in natural settings are a relatively recent development.

Measurement of Significant Behavior in Applied Settings

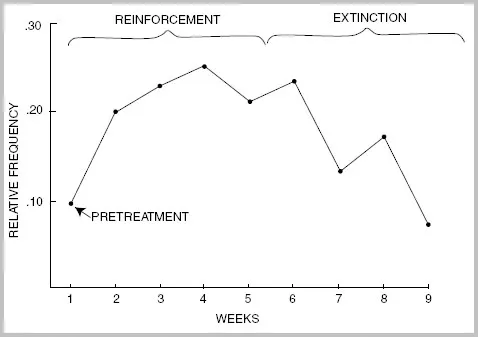

The seminal article “The Psychiatric Nurse as a Behavioral Engineer” by Ayllon and Michael (1959) represented a major contribution to applied behavior analysis. In this case study, problem behaviors of chronic psychotic patients were selected, defined, and measured systematically. In addition to the straightforward counting of such behaviors as “number of entrances to the nurses’ office” or “number of magazines hoarded,” Ayllon and Michael employed time-sampling recording procedures to evaluate “psychotic talk” or the presence of nonviolent behavior at 15- to 30-second intervals during the experimental sessions. The application of this efficient and accurate method of behavior measurement represented a major innovation in applied human research. Various aspects of this method of behavior measurement were, of course, part of human factors engineering in industrial psychology, but the more precise application of regular observation techniques to applied human research represented a largely new development. The reversal design that is described in detail in a later section of this text was also successfully applied by Ayllon and Michael to the hospital ward environment. Figure 1.1 is taken from this published report.

This graph reveals that an initial pretreatment condition consisting of one session was subsequently followed by a reinforcement condition and then later by a return to the pretreatment situation—the original ABA design.

Refinement of Observation and Control Procedures

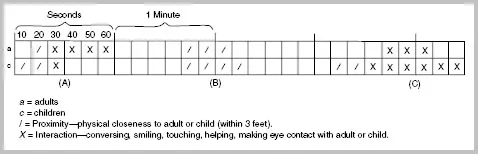

Over the next few years, applied researchers began applying this new technology more extensively to modify deviant child behavior. During the 1960s, researchers such as Don Baer, Mont Wolf, and Sidney Bijou, who were all at the University of Washington at the time, made significant advances relative to changing the behavior of “deviant” children. One of the first refinements came in the area of observation procedures, where a more intensive analysis of moment-to-moment changes in behavior was needed. The 10-second-interval recording method evolved and was an important advance in the precision of behavior observations (see Allen, Hart, Buell, Harris, & Wolf, 1964). Figure 1.2 shows one of the first widely distributed descriptions of this kind of observation technique.

Figure 1.1. Reinforcement and subsequent extinction of the response “being on the floor”

SOURCE: From “The Psychiatric Nurse as a Behavioral Engineer,” by T. Ayllon and J. Michael, 1959, Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 2, pp. 323-334. Copyright 1959 by the Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. Reprinted with permission.

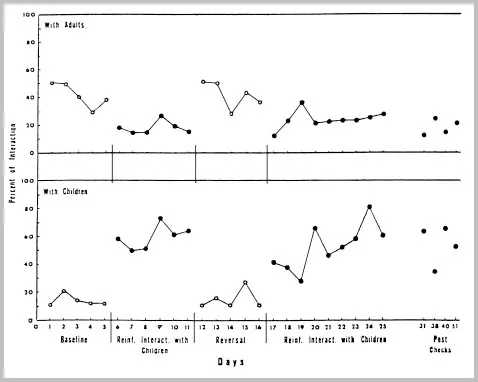

Allen et al. (1964) employed other important advances in data analysis and methodology. Their study elaborated the use of the reversal design by extending the original baseline period over several sessions. This allowed for a better analysis of the inherent variability of preintervention behavior and also made possible an analysis of possible trends in the performance from day to day. In addition, the added refinement of posttreatment checks gave evidence of the durability of behavior change (Figure 1.3). The Allen et al. study also presented evidence of observer reliability to demonstrate that the definitions of behavior were clear and that the features of behavior that were selected by the investigators were, in fact, the major controlling stimuli for the observer. Although today reliability procedures are taken for granted, the implementation of their use in studies such as the one by Allen et al. (1964) typified the movement toward greater precision in behavior analysis in its early years.

Figure 1.2. The original 10-second interval observation form and code

SOURCE: From “The Effects of Social Reinforcement on Isolate Behavior of a Nursery School Child,” by E. Allen, B. Hart, J. Buell, F. Harris, and M. Wolf, 1964, Child Development, 35, pp. 511-518. Copyright 1964 by the Child Development Journal. Reprinted with permission.

The mid-1960s represented a period of exciting advances in the infant technology of applied behavior analysis. The Allen et al. study was accompanied by several other important publications that used similar methodological refinements (see Harris, Johnston, Kelley, & Wolf, 1964; Hart, Allen, Buell, Harris, & Wolf, 1964). These and other studies were the outgrowth of the laboratory-based child research programs described by Bijou and Baer (Bijou, 1961; Bijou&Baer, 1961; Bijou & Orlando, 1961; Bijou & Sturges, 1959) and verified the approach to child development taken by these researchers.

Science and Clinical Success

Perhaps the most dramatic and well publicized of this early series of applied studies involved a 3½-year-old autistic child named Dicky. Dicky had surgery to remove the cataract-clouded lenses of his eyes, and he was in danger of losing his vision if he did not begin wearing prescription glasses (Wolf, Risley, & Mees, 1964). This research program clearly revealed that scientific rigor need not be sacrificed during design of the successful treatment of severely deviant behavior. The program involved the strategy of breaking a complex repertoire into smaller components (tantrums, self-destructive responses, bedtime problems, wearing glasses, throwing glasses, eating problems) and gaining control over each one separately. The result was that the previously hospitalized child was eventually discharged to his parents and was reported to be “a new source of joy to members of his family” (p. 145). These early systematic applications of behavioral principles, together with more refined data measurement and analysis techniques, ushered in a new and exciting era in applied psychology. The well documented and substantial changes in behavior reported in the early published studies suggested that operant methodology would ultimately play a major role in the development of a behavioral technology for treating psychopathology.

Figure 1.3. Percentages of time spent in social interaction during approximately 2 hours of each morning session

SOURCE: From “The Effects of Social Reinforcement on Isolate Behavior of a Nursery School Child,” by E. Allen, B. Hart, J. Buell, F. Harris, and M. Wolf, 1964, Child Development, 35, pp. 511-518. Copyright 1964 by the Child Development Journal. Reprinted with permission.

As we...