eBook - ePub

Learning

A Behavioral, Cognitive, and Evolutionary Synthesis

Jerome Frieman, Stephen Reilly

This is a test

Share book

- 608 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Learning

A Behavioral, Cognitive, and Evolutionary Synthesis

Jerome Frieman, Stephen Reilly

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Learning: A Behavioral, Cognitive, and Evolutionary Synthesis provides an integrated account of the psychological processes involved in learning and conditioning and their influence on human behavior. With a skillful blend of behavioral, cognitive, and evolutionary themes, the text explores various types of learning as adaptive specialization that evolved through natural selection. Robust pedagogy and relevant examples bring concepts to life in this unique and accessible approach to the field.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Learning an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Learning by Jerome Frieman, Stephen Reilly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Psychologie expérimentale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Where Learning Fits Into the Big Picture

We tend to take the ability to learn for granted, perhaps because it is so central to our lives. What we know, how we think about ourselves, and many of the things we do every day reflect what we have learned. The ability to learn and transmit what we have learned to others has done more to shape the course of human history than perhaps any other ability we possess. Thirty thousand years ago our ancestors lived in caves, and it appears from the fossil record that they had the same cranial capacity and presumably the same intellectual capacity as we do (Bolles, 1985). Over the next 30,000 years, we humans learned to farm, domesticate animals, exploit natural resources for minerals, and build structures. We created social systems, governments, religions, cultures, and techniques to preserve and transmit what we learned. The modern, technological, urban society we inhabit is the result of the accumulation and transmission of that knowledge. Much of this accumulated knowledge is passed down to us in books. This is a book about learning, but it is not about learning from books. This is a book about learning from firsthand experience, the way our ancestors first learned to do some of the things we read about in books. We will review some of the ways knowledge can be transmitted between individuals in the last chapter of this book.

Most of what we know how to do and most of the knowledge we use in our daily lives we learned from our parents (or other caregivers), from interactions with our peers, by observing what others do and what happens to them, by direct observation of the relationships between events in our environment, by trial and error, and from the “school of hard knocks.” At an early age we learned to use the “potty” and a language for communication. As we grew older, we learned what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior, proper manners, and social skills. We learned how to ride bicycles and drive automobiles, how to perform at sports and other athletic activities, how to play games, how to win friends and influence people, how to flirt, and how to get out of unpleasant situations. We learned to identify the signs that something good is about to happen and the warning signals of danger. Over time, we developed likes and dislikes and emotional reactions to various things we encounter.

At some point in our lives, we learned that the color of the traffic signal is important: a green light signifies that it is safe to cross the street; a red light signifies that it is not safe. We learned the significance of the traffic signal colors through some combination of verbal instructions (including praise and scolding) and observations of others. What we do when the light is a particular color reflects what we learned.

There is an important distinction here. Although learning is something individuals do, it is not an observable activity. We can observe what someone experiences and how he or she behaves after that experience. We attribute changes in behavior to the prior experience and infer that these new behaviors are learned behaviors. Learning is the name we give to the psychological process (or processes) by which knowledge is acquired from experience. Learned behavior reflects the acquisition of that knowledge.

What Is Knowledge?

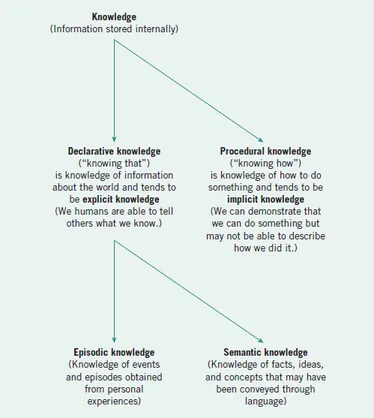

Knowledge is internally stored information about the world and about how to do things. We make a distinction between two types of knowledge: declarative knowledge (knowing that) and procedural knowledge (knowing how).

If learning is the psychological process (or processes) by which knowledge is acquired from experience, then what is knowledge? The philosopher David Pears (1971) notes that no one has yet provided a universally accepted answer to this seemingly simple and direct question. If asked to provide a list of things that we know and activities we know how to do, all of us would readily oblige with a rather long list of both, and we would be sure that the things we know are true. Now, try to write a definition of “knowledge” that separates what we identify as knowledge from beliefs, opinions, and superstitions. The difficulty with any definition of knowledge becomes apparent when we are confronted with another person who disagrees with us and is just as certain about what he or she “knows” to be true.1

The lack of a widely accepted definition of knowledge in philosophy does not stop us in psychology from trying to understand how individuals obtain and store knowledge. Psychologists tend to focus on how experience is encoded and stored in memory as opposed to what knowledge is, and we tend to be more concerned with what individuals believe to be true rather than whether what they believe is indeed true. Thus, for psychologists, knowledge is internally stored information about the world and about how to do things. Notice that this definition includes two types of knowledge: declarative knowledge (knowing that) and procedural knowledge (knowing how; see, e.g., Cohen & Squire, 1980; Ryle, 1949).

Declarative knowledge (knowing that) is knowledge about the world. This includes knowledge about attributes of objects (the sky is blue), general information (George Washington was the first president of the United States), past events (what we did yesterday), the meaning of concepts (freedom is the opportunity to behave in the absence of restraint), the significance of things (red lights mean stop, green lights mean go, amber lights mean drive faster), and the relationships between events (the sound of a siren may be followed by the appearance of an emergency vehicle). Thus, when we state a fact, explain a concept, or describe an event or the relationship between events, we are exhibiting declarative knowledge. Tulving (1972, 1985) argued that in humans, declarative knowledge is stored in two separate memory systems: Facts, ideas, and concepts (which are conveyed to us through language) are stored in a semantic memory system, and personally experienced events and episodes are stored in an episodic memory system. In this book, we are primarily concerned with knowledge obtained through personal experience (episodic memories), although in Chapter 13 we will examine how verbal instructions can sometimes influence behavior.

Procedural knowledge (knowing how) is knowledge of how to do something. Examples of procedural knowledge include skilled actions (driving an automobile, riding a bicycle, typing with a touch typing system as opposed to hunt and peck, playing a musical instrument) and certain cognitive abilities (speaking the English language, solving certain types of mathematical problems). Thus, we are demonstrating procedural knowledge when we do things in an efficient manner.

Another distinction between declarative and procedural knowledge is that declarative knowledge tends to be explicit knowledge; that is, we humans are usually able to tell others what we know. Procedural knowledge tends to be implicit knowledge; that is, we can demonstrate that we can do something but may not be able to describe how we did it. Most of us know how to drive automobiles and ride bicycles, but can you explain to someone else in detail how you do it? We learned to do these things efficiently through practice, not just by observing others or by being told how to do them. (See Figure 1.1 for a summary of the various types of knowledge.)

Throughout our lives we acquire declarative knowledge (both semantic and episodic) about events and the relationships between events. Thus we learn, for example, the names of objects and people, the meaning of things like the colors of traffic lights, and the relationships between events like the presence of certain dark clouds in the sky and impending rain. We also learn how to read, write, and speak certain languages, and we learn motor skills like driving automobiles, tying our shoes, and shooting baskets.

There is a great deal of evidence that declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge are stored in different areas of the brain. People with damage to certain areas of their brains show deficits on either declarative knowledge or procedural knowledge but not both (e.g., Cohen & Squire, 1980; Squire, 2004; Knowlton, Mangels, & Squire, 1996), and functional neuroimaging studies with non–brain damaged people indicate that declarative learning and procedural learning are stored in different locations (e.g., Brown & Robertson, 2007; Hazeltine, Grafton, & Ivry, 1997; Honda, Deiber, Ibanez, Pascal-Leone, Zhuang, & Hallet, 1998; Willingham, Salidis, & Gabrieli, 2002).

It is important for us to keep the distinction between declarative knowledge (knowing that) and procedural knowledge (knowing how) in mind because some kinds of learned behaviors appear to reflect declarative knowledge and other kinds of learned behaviors appear to reflect procedural knowledge (Mackintosh, 1985). Furthermore, some learned behaviors appear to reflect declarative knowledge early in training and procedural knowledge after prolonged training (Adams, 1982; Dickinson, 1985, 1994).

Figure 1.1 The Various Types of Knowledge

How Can We Study Something We Cannot See?

Learning is the psychological process by which knowledge is acquired from experience. Because we cannot observe psychological processes like learning directly, we must infer how they work by observing behavior. We study learning and other psychological processes by conducting experiments to test hypotheses about these processes.

We study psychology in order to understand why individuals do what they do. Although we can observe someone’s behavior and note regularities, there is only so much we can learn from simple observation. How many times have you had a discussion with someone about a third person’s behavior in which both of you had different explanations for what the subject of your conversation did? It is easy to come up with explanations for behavior, but it is much more difficult to come up with the correct explanation. Without some way to test an explanation, we have no way of deciding whether it is correct or not. That is why we bring individuals into the laboratory and observe them under controlled conditions. By systematically manipulating the experiences of our subjects and observing how they behave, we can test our explanations of learning and other psychological processes.

Learning and Performance

We study learning by giving individuals certain experiences and observing how those experiences change behavior. We infer what is learned by relating how given experiences lead to changes in behavior (performance).

How do we know that someone (perhaps you) has learned something? The only way to tell is by observing that person’s behavior. For example, how will your instructor assess what you have learned from reading this book? Most likely, he or she will infer what you have learned from your performance on a test. Fundamental to using test performance to measure learning are two assumptions: One assumption is that students who pay attention in class, take good notes, go home and study those notes, read and study the textbook, and reflect on the information they are exposed to in the course will learn something. Even if we observe you while you are doing these things, we cannot tell whether you are learning; you may be “going through the motions” and not paying attention. (How often have you stared at a page of a textbook and not been reading it?) That leads to the second assumption: Your performance on the test reflects what you learned; that is, good grades reflect that you have learned a lot, and poor grades reflect that you did not learn much. The point is that what your instructor observes when he or she grades your test is not learning but the results of learning. Furthermore, most of us have had the experience of studying hard for a test only to receive a low score. We say we studied, and we believe we learned something, but our performance did not reflect it. We refer to this as the learning-performance problem: the only way we can study learning is by observing performance, but performance may not always reflect learning. The learning-performance problem requires us to consider carefully the tests we use to try to reveal that learning has occurred.

How We Study Learning

We study learning by giving individuals certain experiences and observing their behavior at a later point in time. We attribute long-term changes between pre- and post-experience performance to learning.

In order to study learning (which we cannot see but which may be reflected in behavior), we compare an individual’s behavior at two different points in time: We provide an individual with an experience, and then at a later time we observe the behavior of that individual again. If the behavior at that later time depends on the earlier experience, we infer that the observed change in behavior is due to learning (Rescorla & Holland, 1976). We can do this in a variety of ways: We can observe the individual before and after the initial experience (repeated measurements on the same individual) or compare those who had the experience (the experimental subjects) with those who did not have it (the control subjects). Either way, we infer that learning has occurred when an individual’s behavior at a later time is changed from what it would have been if he or she had not had the earlier experience.

A word of caution is in order: Not all changes in behavior reflect learning. Some changes in behavior can be due to other processes. For example, the experience of engaging in vigorous exercise can bring on fatigue, and exposure to viruses and bacteria can lead to fevers, aches, and pains (as well as changes in behavior), but we do not attribute any of these changes to learning. We attribute to learning some of the strategies the individual employs to overcome the physical distress brought on by the illness when the individual does these things each time he or she becomes ill. Similarly, physical injury to some parts of the body can lead to behavior changes, but we do not attribute these changes to learning, although the individual may learn to compensate for the injury. Some behavior changes may be due to changes in the availability of desirable things (like food, water, or sexual partners) or to unpleasant stimulation. We attribute these changes in behavior to changes in motivation, although motivational states can be aroused as a result of learning and individuals can learn ways to gain access to desirable things and escape from unpleasant stimulation. We attribute changes in behavior to learning when the changes are long term and appear to reflect the acquisition of knowledge about the experience or how to deal with t...