eBook - ePub

Successful Research Projects

A Step-by-Step Guide

Bernard C. Beins

This is a test

Share book

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Successful Research Projects

A Step-by-Step Guide

Bernard C. Beins

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Successful Research Projects: A Step-by-Step Guide is a concise and accessible text that guides students through each component of the research process. Using a step-by-step active learning approach, acclaimed professor and researcher Dr. Bernard C. Beins discusses each of the key actions required for students to confidently develop, perform, analyze, and report the results of their research in a thorough, accurate, and methodologically sound manner. Throughout the text, they will discover not only how to complete each step, but how the steps at any point relate to other aspects of their research and writing.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Successful Research Projects an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Successful Research Projects by Bernard C. Beins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Research & Methodology in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Developing Your Research Idea

In this chapter you will learn about…

- Developing Your Ideas

- Refining Your Research Question

- Generating Your Hypothesis

- Figuring Out What Support for Your Hypothesis Would Look Like

- Preparing for Your Written Paper

When you conduct research, you create new knowledge. It is exciting to think that when you complete your project, you will know something that nobody else in the world knows. Your contribution to psychology may be quite modest; most research projects by professionals make small, incremental additions to our knowledge. But it can be a real contribution nonetheless.

The first step in the process involves developing a research idea. It is a little paradoxical, but coming up with a research idea is both easy and difficult. That is, there is a wealth of potential research questions that you might ask, so finding an interesting topic can be fairly easy, but figuring out exactly how you will approach the research question can be difficult. If an idea has occurred to you, there is a good chance that it has already occurred to somebody else. On the other hand, if others have studied a topic that interests you, you can use their ideas as a starting point for developing yours.

In this chapter, I will present some examples of how you could develop interesting and productive research projects. The examples are intended to reflect the process of developing ideas and certainly do not exhaust the range of possibilities. I hope you will learn about strategies that lead to successful outcomes. Learning how to generate fruitful ideas may be the most important aspect of research.

The process involves quite a few separate steps and a lot of small decisions, but it all starts with your identification of a question that interests you and that other psychologists see as psychologically worthwhile.

Research is a multistep process. The ideas in this chapter relate to other aspects of the research process that you need to consider. But the identification of a research topic is a good place to start. Keep in mind that the later material, like use of PsycINFO to find work relevant to your ideas, will relate to what you are reading here. What you decide now will affect what happens later; at the same time, what you discover later may require that you revisit this chapter.

Developing Your Ideas

The first question to ask yourself as you embark on the quest for a research project is “What am I interested in?” If you want to research a topic, you will find it much more enjoyable if the topic interests you. The idea will really become yours. It is always possible that you will be fascinated by an idea that somebody else proposes, so don’t discount that. But if you take on a task because of your interest in it, you are starting off on the right foot.

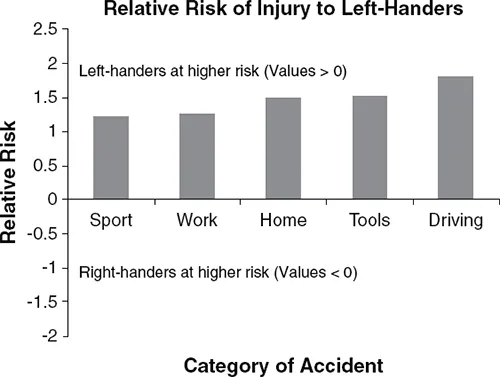

An immediate, but maybe not so obvious, source of ideas is you. Is there something about yourself that makes you wonder? For example, if you are left-handed, you have experiences that are different than those of right-handers in some instances. For example, can openers are constructed so that right-handers can use them most easily. Given that about 90% of people are right-handed, manufacturers are going to produce implements that favor right-handed people, which means that left-handed people will have to adapt. This need to adapt is not always benign. Coren and Halpern (1991) found that left-handers are at greater risk of accidents related to multiple aspects of life, as shown in Figure 1.1. Coren and Halpern also analyzed a set of existing data and discovered that mortality among left-handed people was notably greater than for right-handed people. Accidental deaths seem to play a large part in the death rates of left-handers, who have to adapt to a right-handed world. (After they published their findings, Coren and Halpern received a lot of criticism and even threats by people who thought that the authors were discriminating against left-handed people.)

One question that might arise from this kind of information is whether right-handed people would respond more negatively than left-handed people to opposite-handed implements. Left-handers are used to adapting, but right-handers are not. Or consider classroom desks with tablets made for right-handed people to take notes. Would a left-handed person enjoy a lecture if he or she had to take notes at a right-handed desk? Would it be any different for a right-handed person at a left-handed desk? This kind of research project might provide useful information about helping people enjoy classes more.

Figure 1.1 Relative risk of injury to left-handers by type of accident. Values greater than zero reflect greater risk for left-handers.

Source: Coren and Halpern (1991). Copyright © 1991 American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

Another fact about differences between left- and right-handers is that the two groups seem to respond to space around them differently. Casasanto (2009) found that his research participants had more positive associations to spaces on their dominant side in a two-choice situation. That is, right-handers preferred a given stimulus when it was on their right rather than on their left, and left-handers preferred it the other way around. It would be interesting to see if the liking was on a continuum such that the farther to the dominant side an object appeared, the more positively a person would rate it.

Considering that Coren and Halpern (1991) reported that left-handers are more likely to have accidents related to multiple aspects of life, you might focus on individual sports. Injuries in some sports may be more common among left-handers, but nobody has investigated that. Is it likely that some left-handers are more at risk in some sports? It is a question that has yet to be answered in the psychological literature.

A person’s handedness is a seemingly small factor in one’s life, but it could generate a host of interesting research projects. The same might be true of many different personal characteristics. For instance, would people who are overweight judge silhouettes of others differently depending on whether the silhouette depicted an overweight person? Do people with red hair rate others with red hair more positively than people with dark hair?

Thus, an initial question (e.g., Do left-handers and right-handers prefer stimuli on their dominant side?) can lead to new questions: Do redheads prefer redheads? One point to remember, though, is that it is possible to develop research questions that other psychologists would regard as unimportant or even trivial. So if you were going to see if red-haired people saw other red-haired people more positively than other hair colors, you would need to make a case about why this is an interesting psychological question.1

Casasanto’s (2009) research about the relation between handedness and space preference was tied into the issue of the body specificity hypothesis. This hypothesis postulates that a person’s interaction with the environment shapes the way the person thinks. The question of preference for hair color could be tied to the body specificity hypothesis, but it could also connect to something like the mere exposure effect, in which people develop a favorable reaction to something merely because of repeated exposure to it. In most cases, successful research questions connect to other psychological research.

As you will see in the next chapter, there are ways to find research that relates to a topic of interest to you. You will be able to see whether psychologists have paid attention to it. One of the most common ways to find out about existing research is through the database PsycINFO. As of 2011, there were more than 1,600 entries in PsycINFO in which the word handedness appeared in the title of the work. Some of them might not be of use to you. For instance, 99 of the works with handedness in the title involved nonhuman animals. These could be irrelevant to your project. Nonetheless, the fact that so many citations involve handedness indicates that the topic is of interest to psychologists.

In contrast, you might have to work a little harder in convincing others that a study of redheads is of psychological importance. As of 2011, there were five titles in PsycINFO that used redhead. One involved a study of finches, and another involved ducks, which is not exactly what we had in mind here. There were two studies of perceptions of hair color, and one that discovered that in 1947 (Von Hentig, 1947), there were more redheaded male criminals than you would predict based on the incidence of redheads in the general population. So the question of how people with red hair perceive the world around them is not, in and of itself, of particular interest to researchers. But if you tied your question to the issue of the mere exposure effect (121 citations in which mere exposure effect occurred in the PsycINFO abstract) or person perception (almost 1,500 citations), your idea would be more likely to resonate with other psychologists.

So you might reason that people with red hair are familiar with redheads because they see one every time they look into a mirror. This phenomenon might lead them to feel more positively about redheads than other people do. Or it might be that they favor redheads because such people are similar to them. Or they might not have any different impressions of redheads than they do of any other hair color. You would not know until you investigated.

You can also think about your own behavior (as opposed to your attitudes) in some important aspect of your life. For example, what factors affect your performance on tests in classes? Obviously, there are many to choose from. But one potentially interesting variable is how much sleep you get. Meijer and van den Wittenboer (2004) investigated sleep (and other variables) to see how they correlated with test performance. Surprisingly, the amount of research on the relation between sleep and learning in college students appearing in the literature is fairly small. Investigators have asked some of the obvious questions, but there are many yet to be addressed.

So far, I have identified strategies that will help you develop your research idea. But you should also pay attention to issues that need careful consideration as you develop your ideas. Every idea that you generate is not going to lead to a fruitful research project. Some projects may be trivial, whereas others may be too large or complex; some may be very difficult to complete successfully. Table 1.1 presents some of these issues.

Refining Your Research Question

Once you have an overall topic, you can specify the behaviors or attitudes that you want to measure and the variables that you think are related to or that cause some behavior to occur. After identifying your research topic, one of the next questions involves how you will set up your research.

Investigators adopt different approaches to their research. Those who work in laboratories often use experiments in which they manipulate variables in a controlled setting. Researchers who study people in everyday situations or ask for self-reports about behaviors and attitudes may use descriptive or survey research. Sometimes these categories overlap, but the difference between experimental and nonexperimental research is that experimental approaches permit you to make statements of causation: When condition A occurs, something happens because of it. When condition A does not occur, something else happens. It is the presence or absence of A that determines whether a behavior will occur.

Table 1.1 Potential Pitfalls to Consider When Generating a Research Project

| The Issue | Comment |

| Too big a question | Just about every research project involves a small step beyond previous research, so keep your research question manageably small. Too large a question may require too many participants and too much time on your part. In addition, with very complex research, it can be quite difficult to interpret your results because there can be multiple variables interacting with one another. |

| The “so what” question | Some questions are fairly unimportant. For example, the effect of room color on studying for tests is one that most psychologists would probably consider unimportant. For something like this, you would have to make a case that it relates to recognizable psychological issues (Smith, 2007). |

| Lengthy projects | If you are conducting research as part of a class, your time may be limited to the duration of the academic term. It seems that research never proceeds as quickly as you think it is going to, so it is wise to create a methodology that is as compa... |