![]()

Preparation of the

Soil

by

John Phin

![]()

PREPARATION OF THE SOIL AND FORMATION OF VINE

BORDERS.

HAVING selected a proper site for a vineyard, the next step will be to prepare the soil for the reception of the young vines. It is rarely if ever that ground can be found in a condition fit to plant a vineyard without thorough and extensive improvements, and unless it be in proper order our hopes of success will end in failure and disappointment.

In our remarks on soil it was stated that one absolute necessity is a dry subsoil. No other good qualities can compensate for the want of this, and in most cases it is only to be obtained by thorough draining.

The first great evil obviated by thorough draining is the existence of stagnant water beneath the surface. It is a saying amongst vine-dressers that “the vine cannot bear wet feet.” And nothing can be more true. If the roots be exposed to stagnant water they will become diseased and die off, thus giving rise to weak and ill-ripened though sometimes succulent growth, and hence causing the vine to suffer from the attacks of disease and insects. The grapes, too, will not ripen well, but will remain sour and ill-flavored.

M. Gasparin gives the following observations with regard to the influence which a dry or a moist soil exerts upon the grape: “Other things being equal, we obtain grapes which contain much sugar and little acid from vines grown in a dry soil; more free acid in a moist soil, and much acid, albumen and mucilage with little sugar in a soil which is absolutely wet.”

Another advantage consists in the fact that well-drained land always possesses a higher temperature than that which is wet. This difference amounts to 10° to 12° Fah. and is accounted for by the rapid absorption of heat by the water as it becomes converted into vapor. During this process, too, it is probable that the nascent vapor robs the earth of a portion of the ammonia and gases which it would have separated from the water and retained if it had acted as a filter and the water had passed off by the drains. But however this may be, its effect on temperature is such that Johnson regards thorough draining as equal to a change of climate.

But not only does draining enable the soil to filter all the water which descends upon it, retaining its ammonia, gases and even salts; it is probable that by these means the excrementitious matters discharged by plants, as well as other noxious bodies are washed out of the subsoil or decomposed by contact with the air which penetrates along with the water. In the case of oxide of iron it is probable that a very beneficial effect results from its conversion from the protoxide to the peroxide by means of this influence.

But a change in the chemical constitution and action of the soil is not the only effect of this operation; a no less marked alteration is produced in its mechanical character—heavy lands being rendered light, porous and permeable to the roots of tender plants.

It is unnecessary here to give minute directions for performing such a well-known operation, so we shall merely refer our readers to some of the numerous treatises on that subject. An excellent article on the theory and practice of draining will be found in the “Rural Annual” for 1859 published at the office of the “Genesee Farmer,” Rochester, N. Y.

We may state, however, that in laying drains for a vineyard, it should be borne in mind that after the vines are planted it will be almost impossible to get at the drains in case of accident, without serious detriment to the plants. It will, therefore, be well to construct them in the most substantial manner and also to arrange them so that they will not lie immediately under any of the rows of vines. If they are between the rows it will not be so difficult to got at them as if they lay directly beneath the plants.

The next great requisite in a soil for the culture of the vine is depth. Ordinary soils of from eight to ten inches are by no means deep enough. Twenty inches is the least depth to be relied upon, and, if very favorable results are desired, it should be made three feet. The subsoil to this depth should be thoroughly loosened, and, unless its quality is very inferior, it may be well to mix it with the surface soil—adding at the same time a good supply of manure or compost. We are aware that some horticulturists object to bringing up the subsoil, but we incline to the belief that if it is of such a character as to produce much injury, the site is unfit for a vineyard. When the subsoil is light (except it be pure sand) no harm can result. If it be pure sand, however, it had better remain where it is unless a sufficiency of clay can be found to mix with it. If, on the other hand, it be so clayey as to hermetically seal up the vine borders, we should prefer to let it remain under. But, if possible, a site should be selected where a good depth of tolerable soil may be obtained either naturally or by proper effort.

The advantages incident to depth in ordinary cases consist in the roots being placed alike beyond the extreme heat of summer and the severe cold of winter. Consequently they do not suffer from drought, and are able at once to enter upon their duties in the spring.

For table grapes, we doubt whether the soil can be too deep or rich—not meaning by the latter term, however, saturated with undecomposed organic matter. But observation leads us to doubt the propriety of carrying these features to an extreme in the case of closely-trimmed vines cultivated for wine. It is true that the Western authors (Remelin, Buchannan, etc.—some of them Europeans) advocate this depth and richness. But, if our memory does not deceive us, some of Mr. Longworth’s tenants who have not pursued the most thorough system of cultivation have occasionally escaped evils to which their more skillful and hard-working brethren have been exposed. And perhaps a solution of this mystery may be found above, notwithstanding Mr. Longworth naïvely tells us that he cannot believe that nature ever favors the indolent. Our own experience in this particular department is not sufficient to warrant us in pronouncing a decided opinion on the subject; but the principles of physiology would lead us to believe that if the roots of vines are planted in a deep and rich soil the branches must be allowed corresponding elbow room. If we desire to keep a vigorous plant down we must starve and curtail its roots as well as use the pruning-knife on its branches.

There are two methods of deepening a soil, viz: by the subsoil plough and by trenching with the spade. Both these operations are too well known to require a minute description, though in regard to the latter there are so many and such contradictory directions given in books that we may be pardoned a few remarks in relation thereto.

In order properly to trench a piece of ground the directions given by London are as explicit and judicious as possible. “Trenching is a mode of pulverizing and mixing the soil, or of pulverizing and changing its surface to a greater depth than can be done by the spade alone. For trenching with a view to pulverizing and changing the surface, a trench is formed like the furrow in digging, but two or more times wider and deeper; the plot or piece to be trenched is next marked off with the line into parallel strips of this width; and beginning at one of these, the operator digs or picks the surface stratum, and throws it in the bottom of the trench. Having completed with the shovel the removal of the surface stratum, a second, third or fourth, according to the depth of the soil and other circumstances, is removed in the same way; and thus, when the operation is completed, the position of the different strata is exactly the reverse of what they were before. In trenching with a view to mixture and pulverization, all that is necessary is to open, at one corner of the plot, a trench or excavation of the desired depth, 3 or 4 feet broad, and 6 or 8 feet long. Then proceed to fill the excavation from one end by working out a similar one. In this way proceed across the piece to be trenched, and then return, and so on in parallel courses to the end of the plot, observing that the face or position of the moved soil in the trench must always be that of a slope, in order that whatever is thrown there may be mixed and not deposited in regular layers as in the other case. To effect this most completely, the operator should always stand in the bottom of the trench, and first picking down and mixing the materials, from the solid side, should next take them up with the shovel, and throw them on the slope or face of the moved soil, keeping a distinct space of two or three feet between them. For want of attention to this, in trenching new soils for gardens and plantations, it may be truly said that half the benefit derivable from the operation is lost.”

A more expeditious method of mixing the soil, and one which varies but slightly from the ordinary system, consists in cutting down the bank in successive sections so as to produce theoretically a series of layers of soil and subsoil, but in reality a most intimate mixture of the two. This is best accomplished by opening a very wide trench—say from four to six feet wide. Then throw the top spit off a bank of the same width into the bottom of the trench so as to insure the burial of all insects, seeds, and weeds; cut a width of from six to fifteen inches of the remaining portion of the bank completely down to the bottom, and spread the soil so obtained in a thin layer over the spit formerly thrown in. Then cut down another six to fifteen inches in the same manner, proceeding thus until the whole bank has been cut down and used to fill up the trench. It will now be found that, with the exception of the extreme top spit which is placed at the bottom for very good reasons, the whole soil is sufficiently mixed for all practical purposes.

Another mode of trenching—called bastard trenching—is thus described by a writer in the “Gardener’s Chronicle:” “Open a trench two feet and a half, or a yard wide, one full spit and the shovelling deep, and wheel the soil from it to where it is intended to finish the piece; then put in the dung and dig it in with the bottom spit in the trench; then fill up this trench with the top spit, etc., of the second, treating it in like manner, and so on. The advantages of this plan of working the soil are, the good soil is retained at the top—an important consideration where the soil is poor or bad; the bottom soil is enriched and loosened for the penetration and nourishment of the roots, and allowing them to descend deeper, they are not so liable to suffer from drought in summer; strong soil is rendered capable of absorbing more moisture, and yet remains drier at the surface by the water passing down more rapidly to the subsoil, and it insures a more thorough shifting of the soil.”

A method which we have sometimes adopted, and which we think a saving of labor under some circumstances, is as follows:

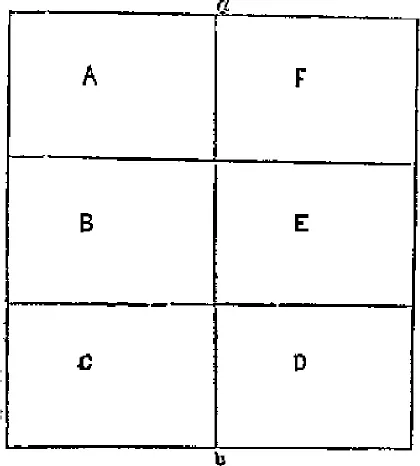

Fig. 1.

Let fig. 1. represent the plot of ground to be trenched. Divide it into two equal parts by the line a b, and instead of wheeling the soil out of A F to the rear of the plot, simply throw that from A out in front.

There can, of course, be no more difficulty in finding room for it there than there would be in obtaining a place for it in the rear. Then dig down the bank B, and with it fill the trench A. B is now a trench which may be filled from C; C may be filled from D; D from E; E from F; and the filling of F with the soil which was at first thrown out of A, will make all even. The wheeling of the soil, which is no inconsiderable item, is thus saved. It is evident, however, that this plan is adapted only to small, or at least narrow plots.

All the foregoing operations prove most beneficial when performed in the fall. At that time the soil should not be finely pulverized, but left in as rough a state as possible so as to expose it thoroughly to the action of the winter’s frost and snow. It should be also well mixed with a good dressing of well decomposed stable manure, and any of those matters mentioned in Chapter XI.

By these means, the ground will be thoroughly enriched by spring, and will not consist of earth mixed with fermenting masses of manure, than which nothing can be more injurious to young plants. In the following spring the land should be raked or harrowed, so as to obtain a level surface of finely pulverized soil, and if it should be lightly forked over it would be none the worse for it.

TERRACES.—From our directions for the selection of a vineyard site, it will be seen that we prefer a gentle elope to the south or southeast. If this slope does not exceed an angle of eight degrees, or a rise of one foot in seven, it will be unnecessary to adopt any peculiar system of arrangement. For a rise of one in four it will be necessary merely to make very slight terraces, the borders being made eight feet wide and half the descent being taken up by the slope given to them, will leave but twelve inches of a terrace, which may be easily secured by a row of sods, boards or stones, or even the earth beaten hard and kept carefully dressed up. But when the inclination of the ground much exceeds this amount, it becomes necessary to form regular terraces which is best done as follows:

Find out the actual slope or inclination of the ground, which is easily done by taking an eight-foot board, and after laying one edge on the ground and levelling the board, find the length of the perpendicular which touches the surface beneath the other end. Thus a d, fig. 2, being the surface of the hill, and c the eight feet board with the level resting upon it, e d, will be the rise in eight feet and e d, less the slope given to the border will be the height of each step or terrace. Having found this, the next step is to cut a perpendicular face half the height of the proposed terrace at the foot of the hill and against it to build a wall as high as may be required. This is best formed of dry stone, though the bank is sometimes left with a good deal of slope, and sodded, the sods being pinned to the face of the bank with stakes until the roots have penetrated suffic...