![]()

The Moon has shone above the Earth with the reflected light of the Sun for four-and-a-half billion years.

CHAPTER 1

The First Astronomers

‘Astronomy compels the soul to look upwards and leads up from this world to another.’

Plato,

Greek philosopher,

4th-5th century BC

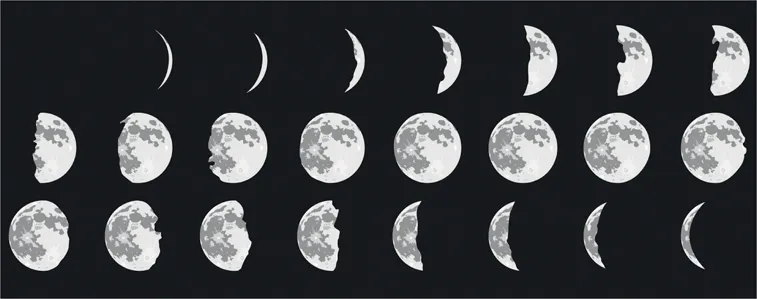

Imagine living in the Stone Age and looking up at the night sky. What would you notice on a clear night? First, the Moon: a bright, shining body that changes shape over the course of around 29 days from new crescent to full circle and back again, and which moves across the sky during the night. Next, there are a lot of bright pinpricks of light. Without light pollution, far, far more stars would be visible than we can see today. You would also see a fuzzy band of dim light that stretches across the sky – the Milky Way.

From seeing to observing

There would not be much to do at night in the Palaeolithic or Neolithic eras, so you might take to observing these objects in the sky with some care, night after night. You might then notice that most of the points of light twinkle, while a few cast a steady light. Those that twinkle move together, rotating during the course of a night around a set point. That point is not directly overhead unless you are standing at the North or South pole. You might notice that the points of light nearest the horizon rise or set over the course of the night and disappear for months of the year, reappearing predictably the following year.

You would probably notice that only a few of these points of light move along their own paths relative to the majority. Most twinkle and stay in fixed positions in relation to one another; they are the stars, originally known as the ‘fixed stars’. Those that move independently and shine steadily are the planets. Long ago they were called ‘wandering stars’ as they seemed to wander among the fixed stars – indeed, the word ‘planet’ comes from the Greek planētēs, meaning ‘wanderer’. As a Stone Age observer, you would notice how they differ from the twinkling fixed stars, but you would not be able to tell that they are fundamentally different bodies.

You might sometimes see a bright light that streams briefly across the sky and disappears – a shooting star or meteor. And occasionally you might notice, if you had been observing carefully in the past, a new star that moves across the sky slowly, night by night, before eventually disappearing. With its dim ‘tail’ of light trailing behind (or, actually, sometimes in front of it), this is a comet – but it’s a rare occurrence.

In the daytime, the sky is dominated by just one body. You would see the Sun rise in the sky in the summer. and follow a predictable path across the sky before setting at a point opposite its rising. Unless you were at the equator, you would notice that the day is longer in the summer than the winter, and the Sun travels higher in the sky summer.

Time lapse photography shows how the stars revolve around the celestial pole over the course of a night.

Except at the equator, the Sun rises higher in the sky during summer than during winter.

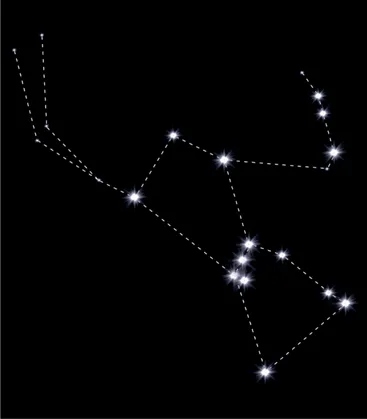

Space and time

It would not take long for a Stone Age observer to notice that the appearance and disappearance of some of the fixed stars matches the seasons. In the northern hemisphere, the appearance of the group of stars now known as the Orion constellation heralds the start of winter. Its disappearance is a sign that warmer weather and more plentiful food supplies are on the way. Just as the path of the Sun across the sky over the course of a day could be used to measure time, so the phases of the Moon could be used to track a longer period – a lunar month. The rising and setting positions of the Sun and some of the fixed stars could be used to track the course of the year. The first human uses of astronomical observation were almost certainly to keep track of time.

THE CHANGING SKY

We think of the night sky as pretty much the same every night, yet a Palaeolithic star-gazer would not see quite the same stars as we do. The northern Pole Star would not be Polaris; instead, the brighter star, Vega, would have been close to the North celestial pole (see page 12). However, as the Pole Star changes, following a cycle of about 26,000 years (see box, page 18), some Palaeolithic observers would have seen Polaris as the Pole Star last time round. Some constellations now seen only in the southern hemisphere would have been visible in the north during some months of the year and vice versa. And as all the stars are constantly moving, some would be in very slightly different places in relation to one another. This is called the ‘proper motion’ of the stars (see page 180), and results from each star moving on its own trajectory independent of all but those closest to it in space. But as these changes happen over thousands of years, much would appear the same to observers on Earth as it does now.

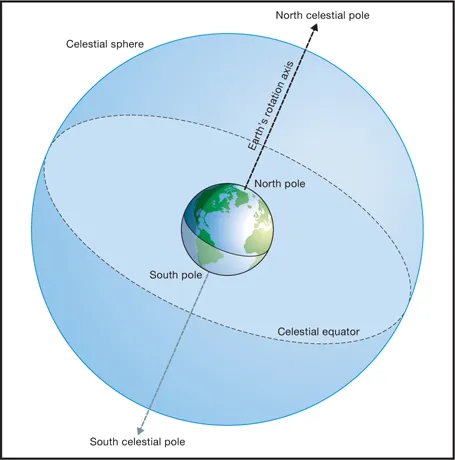

The celestial poles are found by drawing an imaginary line through the Earth from the North to the South pole and extending it into space.

Our earliest ancestors tracked the movement of the Sun, Moon, planets and stars and learned how to predict and interpret them, using their knowledge to plant crops at appropriate times and to anticipate events such as annual floods or rains. But they probably also endowed the heavenly bodies they watched with supernatural significance.

The constellation Orion is visible in the northern hemisphere in winter and in the southern hemisphere during summer.

Day to day

The oldest ‘calendars’ are vast archaeological sites that aligned posts or megaliths (giant stones) with the rising of the Sun or Moon on significant dates, such as the summer or winter solstice. The earliest site so far discovered is Warren Field near Crathes Castle in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, found in 2004. It comprises 12 pits arranged in an arc. At least one pit held a post at some time. It seems likely that the monument performed some sort of calendric function. Archaeologists propose that the pits were used to track the lunar cycle, keeping a record of the lunar months. One of the pits (number 6) also aligns with the position of sunrise at the winter solstice 10,000 years ago.

BABIES BY ORION

A piece of carved mammoth ivory discovered in a collapsed cave complex in Geißenklösterle, Germany, is thought to be the earliest depiction of an asterism – a pattern of stars. Just 14cm (5½in) long, the carving is 32,000–35,000 years old. One side shows a human or part-human figure, taken to be Orion. The other side shows a series of pits and notches. It has been suggested that the pattern acts as a calendar which could be used to time the conception of a baby. If conception coincided with the arrival of Orion in the sky over Palaeolithic Germany, the baby would be born at a time when mother and infant would benefit from the food and warmth of summer for three months before winter set in again.

One suggestion is that the pits at Warren Field might have been used to tally lunar periods over the course of a year. The priest-astronomers marked each lunar month as it passed, perhaps dropping a stone into a pit or moving a post to the next pit. Reaching the final pit meant the end of the year, and they would start again with the first pit. The midwinter solstice could be used to recalibrate. Each time the winter solstice fell at (say) a full moon, they added an extra month to the ending year. This would happen once over three years. That the winter solstice was marked by the middle pit suggests that it came in the middle of the year for the people who used it, meaning their year started in late June (at the summer solstice).

The phases of the Moon over a full lunar month.

LUNAR AND SOLAR CALENDARS

Time is naturally divided astronomically by the Earth’s orbit around the Sun (a year), the Earth’s rotation (a day) and the phases of the Moon. A lunar month (a full cycle from one new or full moon to the next) is approximately 29½ days long. A year is 365¼ days. Inconveniently, a year is 12.37 lunar months ...