eBook - ePub

Kings & Queens of England

A royal history from Egbert to Elizabeth II

Nigel Cawthorne

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Kings & Queens of England

A royal history from Egbert to Elizabeth II

Nigel Cawthorne

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Kings & Queens of England is an entertaining account of the larger-than-life characters that have ruled England through the ages. Divided into easy-reference chapters based on the ruling dynasties of England, it follows the fascinating history of monarchs from the first Saxon kings to the Windsors of the present day.Author Nigel Cawthorne paints vivid portraits of a mixed bunch of rulers ranging from the drunken and debauched merry monarch Charles II to the idealized domesticity and colonial ambition of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Kings & Queens of England an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Kings & Queens of England by Nigel Cawthorne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia británica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia británicaCHAPTER THREE

III

THE PLANTAGENETS

THE PLANTAGENETS |

Henry II (1154–89) |

Richard I ‘the Lionheart’ (1189–99) |

John I (1199–1216) |

Henry III (1216–72) |

Edward I (1272–1307) |

Edward II (1307–27) |

Edward III (1327–77) |

Richard II (1377–99) |

Dates show reign of monarch |

The head of the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd was paraded through the streets of London on a pike after he died in battle in 1282.

The First Plantagenet King

Henry II (r.1154–89) was born at Le Mans in 1133. The son of Matilda, daughter of Henry I and Geoffrey Plantagenet, count of Anjou, Maine and Touraine, he was educated partly in England. In 1150 he became duke of Normandy and when his father died in the following year he assumed the title of count of Anjou. He further advanced himself by marrying Eleanor of Aquitaine, who had recently divorced Louis VII of France (r.1131–80). Louis then tried unsuccessfully to crush Henry, who in just two years had moved from being a landless wanderer to the most powerful man in western France. But his acquisitions did not stop there.

Henry II ruled England and much of France, but he is remembered for the murder of Thomas à Becket.

In January 1153, Henry invaded England in pursuance of his mother’s claim to the throne. There were a number of clashes. King Stephen found his support ebbing away, but fought on in the hope of securing the succession for his son Eustace. When Eustace died in August of that year Stephen lost heart and signed a treaty with Henry. This allowed Stephen to continue as monarch, but named Henry as his heir.

Henry II came to the English throne in 1154 – he was the first in a line of fourteen Plantagenet kings. The dynasty would last for more than 300 years. He was short and stocky with legs slightly bowed from endless days on horseback and his hair was reddish, although he kept his head closely shaved. But his blue-grey eyes were his most distinctive feature. They were said to be ‘dove-like when he was at peace’ but ‘gleaming like fire when his temper was aroused’.

Henry spent his life travelling around his possessions, which stretched from the Solway Firth to the Pyrenees. Although he reigned for 34 years he spent just 14 of them in England. The marriages of Henry’s three daughters had also given him influence in Germany, Sicily and Castile. In addition to that, Pope Adrian IV (in office 1154–9), the only English pope, gave Henry the right to rule Ireland. He obtained the homage of the Scottish kings, took Northumberland back from them and invaded Wales. However, all of his achievements were overshadowed by his quarrel with Thomas Becket, known to history as Thomas à Becket.

THE HOUSE OF PLANTAGENET

Henry II and his royal descendants are referred to as the House of Anjou or the Angevin dynasty. Plantagenet was not the surname of Henry’s father, Geoffrey V, count of Anjou, but it was instead a nickname. Some say he was dubbed Plantagenet because he liked to wear a sprig of broom (or Planta genista in Latin), others suggest that he planted broom to improve his hunting covers. However, the nickname did not become a hereditary surname. His descendants in England remained without a surname for over 250 years, even though surnames became universal for non-royals.

Some historians suggest that only Henry II and his sons Richard I and John I should be known as the Angevin kings while their descendants, particularly Edward I, Edward II and Edward III, should be called Plantagenets. But the only occasion on which the name Plantagenet was used officially was in 1460, when Richard, duke of York, claimed the throne as ‘Richard Plantaginet’.

Becket was a low-born city clerk who rose to become Henry’s chancellor from 1155 to 1162. He was a brilliant administrator as well as being a leading figure at court. He oversaw the repairing of the Tower of London, he brought castles down, he conducted foreign affairs and he raised and led troops. Above all, he was Henry’s closest friend. As such he enjoyed wealth and the trappings of high office. At the time, Henry and the Church were engaged in a battle for supremacy, so Henry came up with a plan. He would appoint someone who would do his bidding as archbishop of Canterbury – his faithful friend Thomas.

Against all expectations, Becket took this new role seriously. First of all he became devout and then he resigned the worldly office of chancellor. Even worse, he opposed Henry’s new taxes and excommunicated a leading baron. But the conflict came to a head over the matter of ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The Church had long asserted its right to try miscreant clergy in its own courts, where they could be punished by demotion or exile but not mutilation or death. On the other hand, the king claimed that he had the authority to try all criminals, including clergy, in his own court. In 1164, Henry passed the Constitutions of Clarendon, which spelled out the relations between the Church and the State. Becket and the bishops verbally agreed to the Constitutions. But the archbishop then changed his mind and appealed to the pope.

Henry demanded that Becket be tried for breaching his feudal obligation. Realizing that the king was out to ruin him, Becket went into exile in France. Henry countered by seizing Becket’s property and banishing his relatives, while the archbishop responded with threats of excommunication. In 1169, the two men met in Montmirail, but negotiation failed and they parted in bitterness.

The king then extended the Constitutions of Clarendon, thereby denying all papal authority in England. He followed that by having his son Henry, the ‘Young King’, crowned by the archbishop of York, rather than by the archbishop of Canterbury. Pope Alexander III (in office 1159–81) and Becket jointly excommunicated Henry and his followers. Fearing that they might interdict the whole country, Henry met Becket at Fréteval and invited him to return to Canterbury.

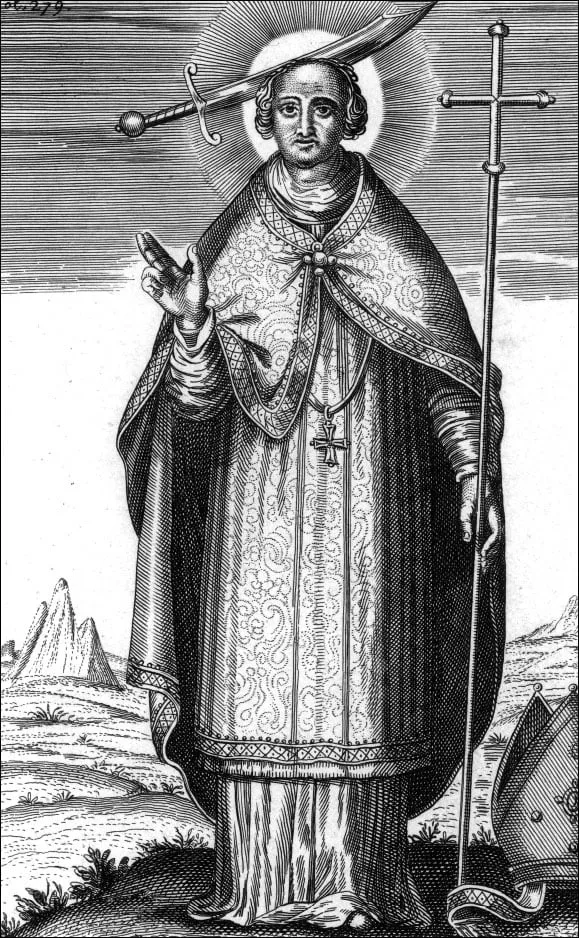

A depiction of Thomas à Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury who excommunicated the king and paid the price.

Becket resumed his role as archbishop of Canterbury to popular acclaim, but refused to lift the excommunications. When he heard this, Henry exclaimed, ‘What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!’ By oral tradition, this was translated into, ‘Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?’

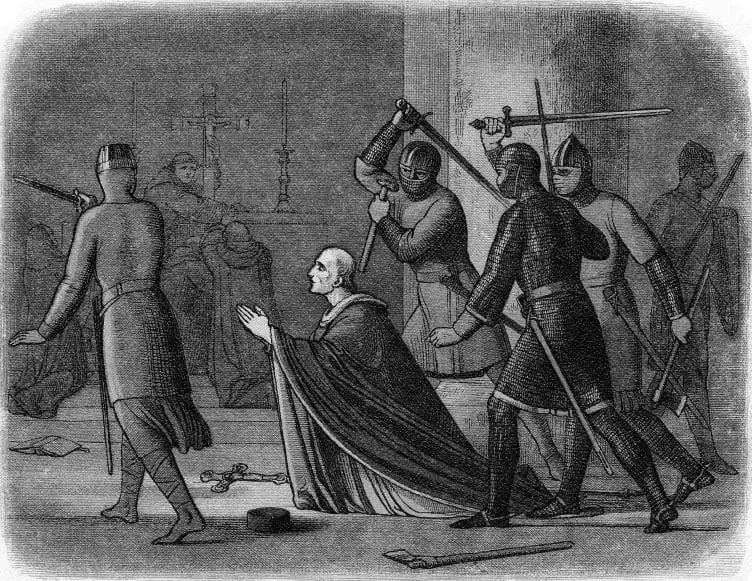

According to tradition, Thomas à Becket was killed by four knights in Canterbury Cathedral. Within days his tomb became a place of pilgrimage and he was canonized three years after his death.

Four knights interpreted Henry’s outburst as a royal command. They sped from Normandy to England and, late in the afternoon of 29 December 1170, confronted Becket in Canterbury Cathedral. In the ensuing struggle Becket was hacked to death by the knights’ swords.

When Henry heard of Becket’s murder, he went into seclusion for three days. Clergy all over Europe were outraged – Pope Alexander refused to speak to an Englishman for more than a week. England was interdicted and Henry closed the Channel ports and fled to Ireland, only returning in 1172. His journey began the English annexation of the island. Then in May 1172 the king met Alexander III’s legates at Avranches, where he submitted to their judgment. He admitted that his words might have prompted Becket’s murder, even though he had never desired his death. Kneeling in contrition, he acceded to the demands of the Church. The episode became known as the Compromise of Avranches.

Although she was 11 years older than her husband, Eleanor of Aquitaine gave Henry five sons and three daughters, all but one son surviving into adulthood. Their four surviving sons – Henry, Geoffrey, Richard and John – quarrelled due to Henry’s habit of ostensibly dividing his possessions among his sons while reserving real power for himself. Even as his co-regent, his son Henry the Young King had no real power. However, he had been betrothed to Louis VII’s daughter Marguerite since the age of five, which reduced the rift between Henry and Louis. Marguerite’s dowry would be Gisors and the Vexin. With a special dispensation from the pope, they were married two years later. In 1172, Marguerite was crowned queen consort of England.

Eleanor of Aquitaine bore Henry II eight children, but was imprisoned by him in 1173 for supporting her sons’ rebellion. On Henry’s death in 1189 she was finally released, and lived for a further 15 years.

Henry the Young King fell out with his father when the king tried to find territories for his fourth son John, at the expense of his brother Geoffrey. John was Henry II’s youngest son and his favourite. He was betrothed to Alys, the daughter of Humbert III, count of Maurienne (Savoy), but because of his brothers’ rebellion he did not get the territories he needed for the marriage to go ahead. Accordingly, he became stuck with the nickname ‘Lackland’.

Rosamund Clifford, the long-term mistress of Henry II, believed to be the mother of two of his illegitimate children.

The rebellion grew when Richard backed his two elder brothers, followed by Eleanor. It was supported by numerous barons and the kings of Scotland and France. Henry II defeated them one by one over the next year. Although Henry became reconciled with his sons, he imprisoned Eleanor in 1173. She remained in custody until his death in 1189. In 1174, not long after Eleanor’s imprisonment, Henry’s liaison with the ‘Fair Rosamund’ – Rosamund Clifford – became public knowledge. The chronicler Gerald of Wales wrote that Henry

‘…having long been a secret adulterer, now openly flaunted his mistress, not that rose of the world [Rosa mundi] of false and frivolous renown, but that rose of unchastity [Rosa immundi]’.

Henry provided for John in 1176 by organizing his betrothal to Isabella of Gloucester. Isabella’s father, the earl of Gloucester, had died without a male heir and it was arranged that his titles and wealth should go to Isabella – and so to John.

There were further disputes among the princes. Richard had inherited Aquitaine at the age of 11, so it is no surprise that he rebelled when Henry II gave it to Henry the Young King. When Henry died in 1183 Aquitaine was passed to John...