![]()

NOBODY KNOWS WHAT’S GOING ON

Hui-neng, the sixth Ancestor, asked: “Whence do you come?”

Huai-jang of Nan-yueh said: “I come from Tung-shan.”

“What is it that thus comes?”

Nan-yueh did not know what to answer. For eight long years he pondered the question; then one day it dawned upon him, and he exclaimed, “Even to say it is something does not hit the mark.”

![]()

I have discovered that it is necessary, absolutely necessary, to believe in nothing. That is, we have to believe in something which has no form and no color—something which exists before all forms and colors appear.

—SHUNRYU SUZUKI

For it is sufficient, I think, to live by experience, and without subscribing to beliefs…

—SEXTUS EMPIRICUS

THE TROUBLE WITH BELIEVING

When I was a child I lived on the side of a hill. It was a broad, grassy escarpment, furrowed by wooded gullies and pierced by outcrops of gabbro, and it rose high behind the houses of my neighborhood. I was told by adults that unicorns romped in those hills.

I don’t think I ever believed this, however. My friends and I often hiked there, and we never saw any unicorns. Besides, there was something in the eyes of the adults—a bit of glee, perhaps—that made them seem less than convinced of their own story.

The question of unicorns, of course, was never a serious one. But I was told other things—things that, even to the adults, were clearly not meant to be far-fetched. These stories were not so easily dispelled, for many people believed them. And I used to wonder, what was required for me to believe?

I was raised in a strict Christian home where religion was a daily matter of serious concern. I was brought up to believe that Christ was my personal Savior. This belief was of extreme importance to me as a child, because I was told that in order to be saved from eternal damnation, all I had to do was to believe in Jesus.

Well, I certainly did not want to be damned for eternity, so I was very motivated to believe what I had been told. But there was something enigmatic about the proposition. I wasn’t sure just what it was I was supposed to do—that is, will myself to do. What was my responsibility? If belief was, as it seemed to be, a moral question, what was I to be held accountable for? As it was presented to me it seemed rather easy. “Just believe,” I was told, “and you’ll be saved.” Just believe—but what could this possibly mean? Surely not just to say that I believed.

The incident that brought this matter to a head occurred when I discovered that my church frowned on the idea of evolution. I had, by the age of twelve, become convinced through my readings that the theory of evolution explained clearly how life occurred and developed on this planet. Suddenly, I discovered that my belief regarding evolution was in direct conflict with my religious instruction. I was in a quandary, for I did not wish to be damned, yet I could not choose to believe as my church would have me believe. I didn’t know what to do.

I knew, if I was to be honest with myself (and I was taught, and believed in, the importance of being honest), that deep down I truly did not believe. To believe in creationism, I would have had to dismiss other things from my mind that I already knew (believed, really) and understood as valid. I was not at liberty to simply start believing any notion that others happened to declare was true, correct, proper or necessary. In other words, I was powerless to make myself believe what I—or others—would want me to believe.

What does it mean to believe, to hold an opinion? It certainly doesn’t mean merely that we say so. It means something very deep. It must mean that deep down we think that such and such is True. It refers to a state of mind that we are powerless to choose.

HOW OUR BELIEFS CHANGE

Since our beliefs do change from time to time, how do we acquire new beliefs if we are not able to simply choose them?

Let’s consider this example, which might reveal more about the dynamics of believing. When Albert Einstein published his general theory of relativity in 1915, he didn’t believe that the universe was expanding, even though certain parts of his theory suggested that it was. He thought that it was just some strange quirk in the math that implied an expanding universe, so by inserting a special term he was able to get rid of the troublesome part that predicted the expansion, which he regarded as an absurdity.1

Then, in the 1920s, astronomers discovered that the distant galaxies were receding rapidly from the Earth—and the more distant the galaxy, the greater its speed of recession. This was an observed fact—physical evidence that implied an expanding universe. Einstein later referred to his alteration of his theory as the biggest blunder of his career.

The point that concerns us here is that, since the 1920s, Einstein believed that the universe might very well be expanding. He didn’t believe that in 1915. In 1915 he thought the idea so absurd that he rejected it in his theory. His mind later changed, but how did that happen? It didn’t change because he simply chose to change his mind. He didn’t just sit down one day and decide to believe that the universe was expanding. Rather, his mind was changed because it was overwhelmed by a new awareness. In the moment in which he became aware of something new, his mind was different. It had changed—automatically, we could say, for at no point did volition ever directly enter into this change of mind. In fact, it never does.

CONFUSING WHAT WE BELIEVE WITH TRUTH

We should not be too alarmed that our will cannot directly determine what we believe. There is nothing inherent in our beliefs that make them True, and this applies whether or not counter beliefs are (or could be) offered. For example, if you believe that everyone likes spaghetti, there is nothing about that belief which validates that proposition; but, more than that, such lack of validation would remain even if no one could find any contrary evidence.

When it comes to spaghetti, of course, what we believe does not pose a serious problem (unless we’re inordinately wild about pasta); but in matters of seemingly greater social consequence, such as questions regarding Truth or moral conduct, relying on what we merely believe could prove to be a needless and disastrous mistake.

People have always believed devoutly, even unto war and death, in a great variety of things that have nothing Real to validate them. Indeed, the very fact that we don’t all believe the same things is enough to draw all beliefs into question.

One way of attempting to get around this problem is to grant the legitimacy of all beliefs. This would be very democratic, and perhaps conducive to peace among people of varying views. But, while this arrangement could possibly lead to a more peaceful world, it would nevertheless do nothing to show us Truth and Reality.

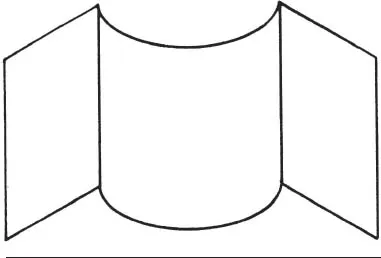

Let’s consider, briefly, just how problematic this issue can become. Suppose two people hold contrary views regarding some phenomenon—such as, say, the object pictured in Figure 1–1. Though each sees it independently, if they enter into a discussion about their independent objects, it’s quite likely that they will believe they are talking about one and the same thing—namely, a single entity “out there” that exists in Reality, that possesses an identity unto itself, and that therefore can be objectified as one and the same for all observers. In this case, however, one person sees a concave surface illustrated, while the other sees it as convex.

Figure 1–1

Let’s say that one of these people insists that only one view is possible—say, that Figure 1–1 is convex, and can only be convex. Their taking this stance indicates that they do not have a strong feeling for how appearances can differ from Reality. “The way I see it is the way it is,” typifies this view.

This view causes problems when it is applied to this simple drawing; when such a view is applied to moral questions—e.g., when does human life begin, or when is war justified—the immediate and inevitable result is conflict, often anger, and sometimes violence.

It is not difficult to see that Figure 1–1 can in fact be viewed in different ways. For many of us, it is equally easy to see how certain moral questions can also be approached and seen in more than one manner. The person who can see how a moral issue can be viewed in different ways is likely to appear quite liberal, tolerant, magnanimous, open, and perhaps even more intelligent than the stubborn dogmatist.

Many philosophers, however, are not impressed by those who take this more generous view. Their reason is that while the first view—that of the dogmatist—clearly does not allow one to fully appreciate the subtle and potentially troubling ambiguities of life, the second view simply makes the morally weak assertion that “for you, it is like that, but for me, it is like this.” If we insert actual objects into this view, it begins to appear absurd. “For you it is convex but for me it is concave.” “For you abortion is murder but for me it is not murder.” These are not compelling moral arguments. In fact, they only carry us deeper into a morass of endless questioning where, as in the case of abortion, we soon begin to discuss not just patently absurd, but inevitably dead questions: Is a fetus human? When does it become human? We may as well debate seriously the question regarding the primacy of the chicken or the egg, or how many angels can dance on the head of a pin. In very short order we are lost and drifting without a mooring.

Philosophers have pointed out that such arguments carry us into a morass because (1) either we would have to assert that the object under discussion is both ways in Reality (a paradox), or (2), we end up saying that everything is to each person such as it is to that person (a tautology). We find in either case that we haven’t really described anything meaningful.

We can’t seem to get to the bottom of things. Though it seems quite evident that there are such distinctions to be made, when we try to pin down just what it is that we mean by them, we find we can’t do it. We never seem to touch upon any reality that is distinguishable from appearance—and appearances, we have learned, often deceive. We seem unable to clarify this dense problem of Reality. We are, in short, very prone to falling back into the realm of the dogmatists.

We may argue that at least when we grant the legitimacy of the views of others, we will not be contributing to the hatred and fighting that have gone on since time immemorial among peoples of differing beliefs. But at what cost must we hold such a view? Where does this seemingly more magnanimous view get us? When it comes to the profound questions of human life and moral conduct, we find that we only sink deeper into the mire of human misery. Where at least the dogmatist has something to believe in that gives them a sense of purpose (however deluded it may be), the relativist is without even this and is instead left vulnerable to a feeling of utter meaninglessness.

This sense of meaninglessness is a prevalent problem among intelligent, educated people these days. When carried to the extreme, it reduces the individual to either (1) becoming a zealot out of desperation and thereby sacrificing their intellectual integrity; or (2) living with the sense that ultimately there is no hope or meaning to human life.

In this book we will explore a third possibility that lies outside these two wretched alternatives of utter ignorance or utter despair. By this I do not mean to propose the weak alternative of becoming, in some manner, a fake—i.e., someone who doesn’t believe but who pretends to, or who does believe but pretends not to. All such positions are bound by belief, and that is our chronic problem. Rather, I...