Copyright © 2022 Kathy Friedman

Published in Canada in 2022 and the USA in 2022 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

House of Anansi Press is a Global Certified Accessible™ (GCA by Benetech) publisher. The ebook version of this book meets stringent accessibility standards

and is available to students and readers with print disabilities.

26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

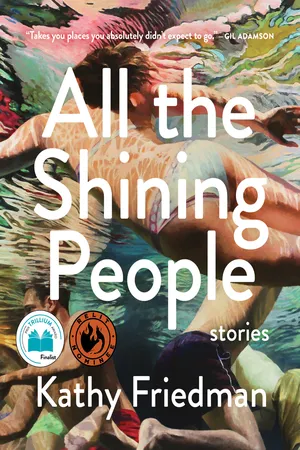

Title: All the shining people : stories / Kathy Friedman.

Names: Friedman, Kathy, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210375833 | Canadiana (ebook) 20210375892 |

ISBN 9781487010409 (softcover) | ISBN 9781487010416 (EPUB)

Classification: LCC PS8611.R5315 A75 2022 | DDC C813/.6—dc23

Book design: Alysia Shewchuk

Cover artwork: Anne Leone, Cenote Azul #2, 2014.

Acrylic on linen, 36 × 72 in. Private collection.

House of Anansi Press respectfully acknowledges that the land on which we operate is the Traditional Territory of many Nations, including the Anishinabeg, the Wendat, and the Haudenosaunee. It is also the Treaty Lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit.

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada.

At the Bottom of the Garden

We lived in Durban, South Africa, until I was six and a half. At night, small lizards encircled the house and pressed their white bellies against the windows, enchanted by the light. Longing to be inside with us, cockroaches spread their stiff wings and threw themselves at the glass veranda door. Once we found a shed snakeskin on the back step. The snake was thicker than our father’s wrist.

Early in the morning, before the day began to steam, our father would lead me into the bathroom and lift me onto the basin, where I sat, knees to chin, watching him shave. From the moment he wet his shaving brush until the last remnants of foam were washed from his face, he didn’t look at me, but I could tell he liked having me there, having me close. I stayed quiet so he could concentrate. When he finished, he let me stick bits of toilet paper to the spots of blood left behind. This was how I worshipped him.

Sunday afternoons, after a braai in the garden with all the cousins, half drunk from the whiskies our grandpa kept pouring, our father would have a sleep. I’d settle in the family room with my little sister to watch TV. Reruns of Shaka Zulu were always on. We’d crunch Simba chips and drink sweet milky tea while Shaka impaled his rivals on tall spikes, and the walls seemed to shake with our father’s dreams. Shaka was a great and ruthless king, but just watch him when the White men bring trinkets, turning his face side to side, having never seen himself in a mirror before. If Lindy, our nanny, had finished her work for the day, she was allowed to join us. She always sat on the floor. Sometimes, my head hot from the tea, I’d fall asleep in Lindy’s lap before the program ended, carried off by her breathing and our father’s snores.

Nearly every week, Lindy used to take us to the zoo in Mitchell Park. She’d thump down on one of the benches meant for her race, slip her feet from their rubber sandals, and fan herself with a magazine. If there were other children, she’d talk with their nannies in her clicking language and leave us on our own. One time, a huge grey bird, thinking I wanted its babies, swooped down to claw and peck at me, and someone else’s nanny had to step in to drive it off. It took six stitches to sew my scalp back up. Everyone said I was a brave boy because I hardly cried. That night, from the top of the stairs, my sister Leora and I saw Lindy, head low, getting a talking-to from our father in the entrance hall, and by the end of the month she was gone. She left her pale pink uniform folded in the servant’s hut at the bottom of the garden. I began having dreams that made me wake up calling for her. But Lindy didn’t come back. Our new nanny was gap-toothed and lazy, our mother said, always giggling over the gate with her boyfriends. Finally, after two months, Lindy returned to us, walking sway-hipped and proud across the garden again with a basket of clean-smelling laundry on her head.

Soon, Uncle Noah and Auntie Cheryl took our cousins Sam, Rachel, and Levi to Australia for good. It was raining the day they went, hard slashes that scoured the leaves and dirt from flower beds and pushed our cousins into a rented hatchback bound for Jan Smuts Airport. We stood under the dripping eaves of their empty house and waved and waved. The following Sunday, our father made a l’chaim to “the severed limb of our family’s tree,” his face red from whisky and the smoke off the braai, and everyone talked about the time Levi licked battery acid off his arm, thinking it was marinade, and how shikkered Uncle Noah had been at our parents’ wedding, until our mother said, “Oh for heaven’s sake, they’re not dead. I just talked to Cheryl this morning,” and even the birds in the pawpaws went quiet.

One day, during a family meeting at the kitchen table, our father announced we were moving to Canada. He was a judge, and his decisions were final. Men started coming to the house to pack our things into boxes. My mom’s best friend kept teaching me to write with her thick red pencils, until one afternoon she said this was to be our last lesson, and she knelt down, wrapped her freckled arms around me, and leaned her chin against the top of my head. When our granny and grandpa came for Pinky, he nearly chomped Grandpa’s hand off. “Isn’t it incredible,” my mom said, while Granny bandaged Grandpa’s hand, “how a dog just knows these things.”

In London, rain beaded the streetlamps and the black roof of the taxi that took us to the hotel. Our mother liked to tell us how advanced the English were, how civilized, but the streets here were just as crowded as the Indian market back home, only duller, with tall rows of flats crushed miserably together, and the weather far greyer and colder than the mild Durban winter we’d been told to expect.

We had to share a room at the hotel, my parents in one bed, me and Leora in the other, the lamps off and a panda bear plugged in beneath the window, its weak glow smothered by the heavy curtains, so that each time Leora’s breathing deepened, a dark terror laid its fingers across my throat and I coughed. My father became wild with anger at me as the night wore on. Finally, just before dawn, he shoved me into the bathroom, but rather than sitting me on the basin he yanked me across his lap and laid on three surprising strikes with his leather belt. Afterwards I curled up on my side crying silently. He’d smacked me many times before, but never with a belt.

When my mom found out about it, she said I could choose any toy I wanted from Hamleys, the world’s biggest toy shop. But first we had to see the palace where the Queen lived, guarded by serious men in tall furry hats. My parents were proud to show us the royal palace. They said she would still be our queen in Canada.

We took so long at the palace that we only had two hours at Hamleys to explore seven floors full of toys. Then we’d have to go back to the airport for our flight to Toronto. I stayed with my mother while Leora bounded off with my father. We were to meet back at the cash registers at two on the dot.

My mom and I agreed to hurry past the bears on the ground floor — pink, purple, yellow, and green, striped and spotted bears — some the size of a birthday card, some as big as my mom. In one aisle, I found a five-foot-tall Paddington Bear and rocked him back and forth in a death grip until my mother said, “We’re not taking that on the plane, Ken Joel Kaplan,” and pulled me away, past the plush dolphins and kangaroos and dinosaurs and unicorns, towards the escalator. As we glided up to the next floor, I noticed an open door which led to a large storeroom, where a ginger-haired shop assistant was feeding live goldfish, one after another, into an enormous tank. Twice I saw a pair of great snapping jaws close over the wriggling fish, but before I could point out the scene to my mother, we’d arrived on the next floor.

It was the science and games floor. My mother said we should keep going, I was still too young for these things, but I reminded her that she’d promised me I could choose any toy in the shop. All along the wall, candy-coloured test tubes steamed and hissed above silent blue flames. Through the long corridors of spy kits and detectors of pirate treasure, we made our way to the back. Passing through velvet curtains, we saw a screen churning with planets and faraway galaxies. Thumb-sucking boys and girls waited their turns to examine the universe’s mysteries through a toy telescope. I wanted to stay and have a look but my mother reminded me we didn’t have much time. We parted another curtain and entered a long passageway, its high walls hung with faded tapestries, its ceiling the same porridge grey as the sky over London. Or maybe it really was the sky; it was impossible to tell because the passage was full of pale-yellow smoke that stung the backs of our throats. Above us, a shiny purple helicopter raced and dipped. A matronly saleswoman, her skin mottled like old parchment, leaned from the window and asked if I wanted a turn at the controls. But my mother tapped her watch again, so we had to shake our heads sadly and walk towards the exit sign, glowing green through the smoke at the end of the long hall.

That door led us straight to another escalator, this one heading to the upper levels of the shop. It was already ha...