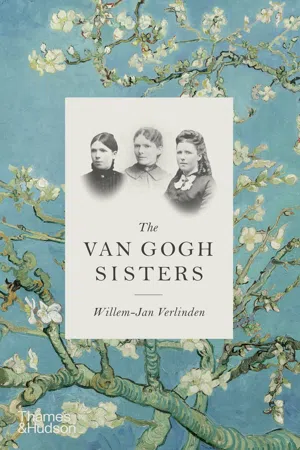

![]()

CHAPTER 1

It Was Terrible. I Shall Never Forget That Night

Nuenen, 1885–1886

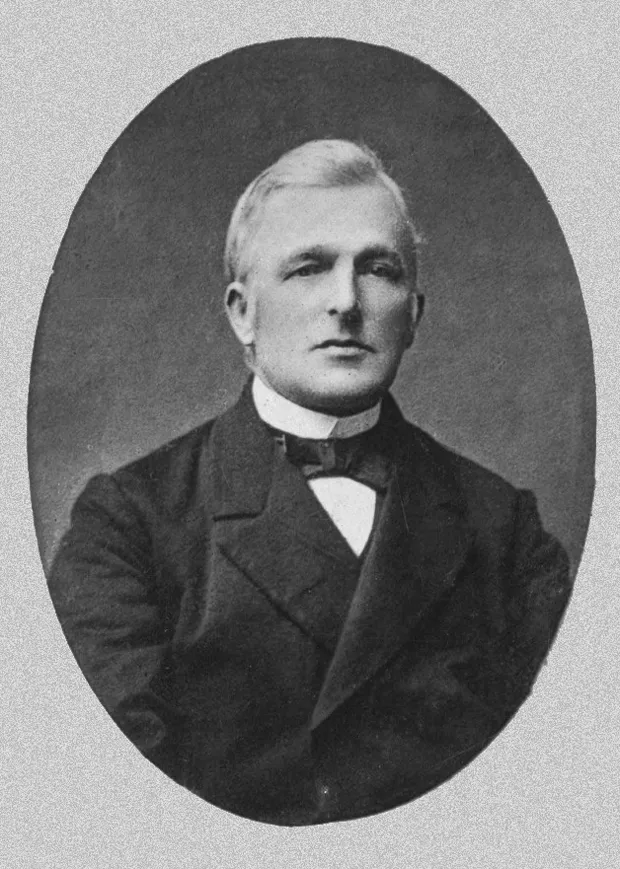

In 1885, the Protestant Van Gogh family was living in the village of Nuenen, in the Dutch province of North Brabant. On Thursday 26 March that year, Reverend Theodorus (Dorus) van Gogh, father of Vincent van Gogh and his five siblings, arrived home after a long journey across the heathland and collapsed at the parsonage doorstep. The family’s servant was just able to catch the minister as he fell, and word was sent to his youngest daughter, Willemien, who was visiting neighbours. She ran home and attempted to resuscitate her father, but it was too late: Dorus van Gogh, known as Pa to his children, had died, aged sixty-three.1 Uncle Johannes van Gogh and Aunt Wilhelmine Stricker-Carbentus, who met coincidentally on the train to Eindhoven, were the first to come to the house and assist the family.2

Dorus van Gogh. Date and photographer unknown.

The Protestant reverend was buried in the Tomakker general cemetery, at the foot of Nuenen’s old tower, on 30 March 1885. The burial site could be located from a distance because of this tower, also visible from the garden of the parsonage. Vincent made a drawing of just this angle with pencil, pen and ink in March 1884 (see pl. III). In a letter to his colleague and friend Anthon van Rappard he described the woman in the composition as a black fairytale in the form of a splotch, rather than as an example of the human body worthy of imitation.3 The date of Dorus’s funeral, 30 March, held great significance for the family: not only was it the date of Vincent’s birthday in 1853, but also of the family’s first son, also named Vincent, who had been stillborn in 1852.4

Vincent van Gogh, Parsonage at Nuenen, 1885. Oil on canvas, 33.2 × 43 cm (13 × 17 in.).

Dorus’s sudden passing escalated a tension that had been smouldering in the family for years. Vincent, approaching his thirty-second birthday when his father died and still living in the family home, had become more and more of a nuisance to his parents. His eccentric habits and occasional outright belligerence were an embarrassment to Dorus, whose authority over his flock depended in part on his family’s comportment. Not long after the funeral, Anna, the eldest of the Van Gogh sisters, and Vincent had an explosive argument over Vincent’s continued presence at the family home, which she and her siblings felt threatened not only his mother’s well-being but also the family’s standing in the village – just as he had their father’s.5 It was this confrontation that provoked Vincent to leave his home, and the Netherlands, for good. By the end of the year he moved to Antwerp, and from there travelled to France to pursue his dream of becoming a painter.

His sister Willemien, known as Wil, was just twenty-three years old when she found her father dead at the family home. She was a caring young woman who was close to her siblings and mother (who the children called Moe, pronounced ‘moo’). While her older brothers and sisters each left home in their turn, Willemien stayed with Moe to help look after the household, and moved with her to the town of Breda after Pa’s death. Dorus had grown up there; his father, Vincent, had been minister at the Grote Kerk (Main Church) and pastor at the Koninklijke Militaire Academie (Royal Military Academy). Moe and Willemien lived in Breda for only a few years before moving to the university town of Leiden, where Anna lived with her husband and daughters.

Willemien was to make very different life choices from her sisters Anna and Elisabeth (Lies): she never married or had children, and pursued independence. In Leiden she found work as a teacher of scripture and as a nurse – caring for the poor, the weak and the elderly, as she had always done. In doing so, she was exploiting the limited employment opportunities available to women. Social work – education, caring and nursing – was the only sector in the Netherlands in the second half of the nineteenth century that offered paid work to women from the upper middle class, to which the Van Gogh family belonged. Willemien became a committed participant in the first wave of Dutch feminism, travelling more and more to The Hague and Amsterdam, where as well as calling on family she visited friends, who often shared the same background and were, like her, beginning to question the position of women in society. Their discussions and initiatives were fuelled by similar movements in the United Kingdom, France and the United States. These women became increasingly organized; their activities expanded over the decades and focused on securing equal rights for women, such as female legal emancipation, women’s suffrage, and access to education – including to universities – and paid work.

Vincent van Gogh, Willemina Jacoba (‘Willemien’) van Gogh, 1881.

Pencil and traces of charcoal on laid paper, 41.4 × 26.8 cm (16¼ × 10½ in.).

Anna van Houten-van Gogh, 1878. Photographed by J.F. Rienks.

Vincent and Willemien were both ‘different’ – different from their sisters Anna and Lies, and from their brothers Theo and Cornelis (Cor) – in their rejection of society’s prevailing norms. Their similarity to each other could be seen from an early age, in the difficulties they both experienced at school, and which continued into later life. They were both socially engaged and very creative, and shared a deep interest in religion, art and literature. They both remained unmarried and never had children, and struggled with their mental health, which they discussed openly with each other. Willemien probably also gradually discovered that she was different in her sexuality.6 They were above all willing to fight for ideals that were perhaps a little too far ahead of their time, and refused to conform to the expectations of those around them. Pa and Moe were socially minded with strong artistic leanings, and ensured that their children received a broad education. Thus, rather than hiding their differences, Vincent and Wil each became pioneers in their own distinct way – Vincent with his progressive art, and Wil with her social causes.

Yet the course of their lives was deeply influenced by these dramatic events: the death of their father Dorus and the subsequent argument between Vincent and Anna. Willemien was haunted by the image of her dying father. She wrote to her friend Line Kruysse that Pa had left the house healthy and well in the morning, but collapsed lifeless in the doorway when he returned that evening: ‘It was terrible. I shall never forget that night….I hope that you will be preserved from ever experiencing something like that.’ In the same letter she reflected on her brother Vincent, commenting that she thought he had been embittered by his fight with her eldest sister, and expressing her fears of the conflict’s impact on the family.7

Anna’s anger was the outcome of a long-standing discord between Vincent and his father. In 1881, when the family was living in the village of Etten, Vincent had refused to attend church at Christmas, undermining Dorus’s authority as the minister of the Dutch Reformed church.8 Vincent frequently disregarded his father’s wishes in the family home as well, often in the presence of his siblings. For his part, Vincent felt that his father did not take his ambitions – first to become a minister or an evangelist, and later a good artist – seriously. Yet Vincent was willing to stand up for himself, for a new life worth striving for.9 Father and son quarrelled frequently; the other family members regularly wrote to each other on the subject. Yet two of the most important tenets of Dorus’s upbringing of his children were unity and the desire for togetherness, so Vincent was deeply dismayed when Anna reproached him for arguing so much with Pa and alleged that he was a burden on Moe. He was also hurt that none of his other siblings had stood up for him, although Theo had also previously tried to encourage Vincent to leave home. Vincent seems to have been especially disappointed in Willemien. He had always considered her an ally, but the aftermath of the incident had abruptly put paid to that assumption. For Wil, as for the other siblings, her mother’s well-being was more important than her eldest brother’s ability to stay in the parsonage after Pa’s sudden death. For a time, Vincent did not even want to see her.10

Vincent moved into the attic above the studio he had for a time been renting from the Catholic sacristan Schafrat in the centre of Nuenen. On 6 April 1885 he explained to Theo that it was not for his convenience that he lived there, but to diminish the chance of future accusations, especially from Anna: ‘however absurd those reproaches were and her unfounded presumptions about things that are still in the future – she hasn’t told me she takes them back. Well – you understand how I simply shrug my shoulders at such things – and anyway, I increasingly let people think of me just exactly what they will, and say and do too, if need be. But consequently I have no choice – with a beginning like that, one has to take steps to prevent all that sort of thing in the future. So I’m absolutely decided’.11

Vincent thought there was also a practical reason that his sisters had wanted him to leave the parsonage; Moe could take in a lodger and thus generate some extra income. Living in the parsonage was simply too expensive for her.12 Two months later he was still very disgruntled about the events after Pa’s death and the settlement of his estate, writing to Theo that he was disappointed it was settled entirely in his mother’s name. He also defended himself for the little time he spent with his mother, writing that visiting ‘Occasionally, from time to time, is sufficient. I find them at home (I know – contrary to your opinion, and contrary to their own opinion) very far, very far from sincere’.13 It was not Moe, but his sisters who were on the receiving end of his criticism: ‘since I foresee that the characters of the 3 sisters (all three) will get worse not better with time’.14 Vincent wrote that they irritated him, and that he found them downright unpleasant;...