Pretentiousness: Why It Matters

Start with the basics. (Presumably the least pretentious place to begin.) The Latin

prae — ‘before’ — and

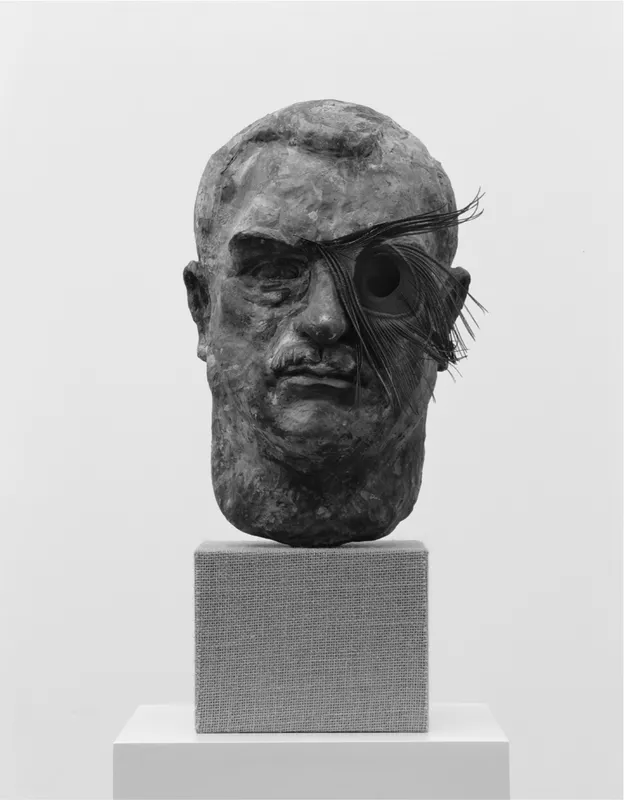

tendere, meaning ‘to stretch’ or ‘extend’, give us the word ‘pretentious’. Think of it as holding something in front of you, like actors wearing masks in the ancient Greek theatre.

Or imagine yourself on a medieval battlefield, carrying a shield. In heraldry, the term ‘escutcheon of pretence’ describes the coat of arms of an heraldic heiress, incorporated into her husband’s own arms on the death of her father. In the absence of other male inheritors, the heiress’s husband would ‘pretend’ to represent the family. A shield was needed to protect your body in combat — held in front of you, prae tendere, like the actor’s mask hides the face — but it also carried a design that boasted of your power and political authority. Your pretence was your protection, and could also make you into a target. (Since the fourteenth century, the Russian army has used a strategy of deception they call maskirovka — ‘something masked’ — to hide, deny, or divert attention away from real military manoeuvres.)

In politics the claimant to a throne or similar rank was known as a ‘pretender’. Upheavals in England, Scotland and Ireland brought about by the ‘Glorious Revolution’ in 1688, for example, saw the overthrow of the last Stuart king, the Catholic James II, by the Protestants William and Mary. Two ‘pretenders’ aiming to restore the Jacobite monarchy subsequently made claims to the English crown. (The most famous of these was the ‘Young Pretender’, Charles Edward Stuart, also nicknamed Bonnie Prince Charlie.) To be called a ‘pretender’ was not necessarily an insult; the issue was the legitimacy of the claim you held before you, prae tendere. Authority was recognized on the basis of your political allegiance and religious belief, not questions of truth or falsity. This pretence was not an act. It was a matter of blood and God.

Go back to the actor and the mask. In classical Greek theatre the word hypokrités — from which we get ‘hypocrisy’ — was the standard term for actors, deriving from the words hypó (‘under’) and krisis (‘decide’, ‘distinguish’ or ‘judge’). It was a way of describing a dissembler, the faces of the mask and the actor beneath it. When St Paul, in his Epistle to the Romans, wrote ‘Let love be not hypocritical’, he used the word in this Greek sense, meaning ‘actor’. Paul meant that love should not hide itself behind a mask representing love, or use words signalling it insincerely.

‘Man is least himself when he talks in his own person,’ said Oscar Wilde. ‘Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.’ Well, maybe. It depends on the time and place. Theatre, cinema and broadcasting provide the professional licence to wear one. We derive pleasure from the deceits of the stage illusionist, whose acts of fakery we pay money to watch. (Magician James ‘The Amazing’ Randi describes himself as ‘an honest liar’.) In carnival and ritual too, the mask is socially sanctioned. Outside these fields the actor’s mask is suspect. So we smear it with the brush of immaturity, dismissing it as ‘pretending’.

Pretending is what kids do to figure out the world. Children do not put on airs. A child might be precocious — from the Latin prae, meaning ‘before’, and coquere, ‘to cook’, that is, pre-cooked or ripened early — but it’s rare that a child is called pretentious. That insult is reserved for their pushy parents; pretending is what’s done at the kids’ table, pretension goes on over the wine and cheese course with the grown-ups. Pretending reminds adults of childish things long put away; of imaginary friends, of the companionship found in favourite teddy bears and dolls, in toys we imagined to have distinct personalities, and the stories we swaddled them in. To pretend is to live in denial of ‘real’, grown-up problems. It’s child’s play.

And a play is also what professional actors are employed to make onstage in theatres. ‘Acting is a reflex, a mechanism for development and survival,’ writes theatre director Declan Donnellan in The Actor and the Target. ‘It is not “second nature”, it is “first nature” and so cannot be taught like chemistry or scuba diving.’ Acting is a tool of every social interaction we have from birth. ‘Peek-a-boo,’ says Donnellan, is the first play a baby enjoys,

‘Born Originals, how comes it to pass that we die Copies?’ asked Edward Young in his Conjectures on Original Composition. Young would argue that mimicry blots out individuality. But mimicry is a mechanism by which we become socialized, by which we make ourselves human. It doesn’t take a sociology Ph.D. to recognize that we pretend every day. Pretend to be absorbed in a book to avoid catching the eye of a stranger on the bus. Pretend to be pleased to see your boss when you arrive at the office. Putting on a suit allows you to pretend you’re efficient or powerful when you would rather be in your pyjamas in front of the TV. Wear jeans and a T-shirt to the office to pretend to your co-workers you are laid-back when your personality tends towards the uptight. It’s hard to admit to pretending because in Western society no one likes a faker. Great store is placed on ‘keeping it real’. We tell those with unrealistic expectations to ‘get real’, ‘face reality’ or ‘wake up and smell the coffee’, as if the rest of their activities were a dream.

Yet we value dreams. ‘We are such stuff as dreams are made on,’ wrote William Shakespeare. Four hundred years later his line from The Tempest would be printed on motivational posters, accompanying a soaring eagle or spectacular sunrise. ‘Keep hold of your dreams,’ we advise. ‘What’s your dream job?’ ‘Who is the man/woman of your dreams?’ The contradictory impulses to both dream and face the truth find uneasy reconciliation in the language of the workplace. ‘Act like you mean it.’ We refer to ‘acting on behalf of’ a person or organization, or ‘playing a part’ in a project. Your boss assesses you on your ‘performance’ in the job, a ‘role’ that might be rewarded with ‘performance-related pay’. ‘Dress for success,’ say the careers gurus. ‘Dress for the job you want, not the one you have.’ ‘Look smart.’ The cover headline of the January-February 2015 edition of the Harvard Business Review reads: ‘The Problem with Authenticity: When it’s OK to fake it till you make it’. The article explains ‘Why companies are pushing authenticity training’ and advises its readership that ‘by trying out different leadership styles and behaviours, we grow more than we would through introspection alone. Experimenting with our identities allows us to find the right approach for ourselves and our organization.’

Play, according to psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott, allows a child to see, risk-free, what happens when their internal world engages with the external one. Yet by the time you reach an age at which you can legally drink, vote, drive, consent to sex, or get married, it’s presumed you know where to draw the line between fact and fantasy, where innocent play congeals into pretension. And nobody wants to be accused of that. In his 1996 diary, published as A Year with Swollen Appendices, musician Brian Eno describes how he

If ‘pretending is the most important thing we do’ then what bred such discomfort with it?

‘DON MCGRATH: You know that Shakespearean admonition, “To thine own self be true?” It’s premised on the idea that “thine own self” is something pretty good, being true to which is commendable. But what if “thine own self” is not so good? What if it’s pretty bad? Would it be better, in that case, not to be true to “thine own self?”’

— The Last Days of Disco (1998)

Plato hated actors. (So too did my Irish grandmother, who reserved the term ‘actor’ for one of her sharpest put-downs.) The mimesis of theatre, thought Plato, could only lead to self-corruption; if you played a slave you might end up servile off-stage too. He argued that imitation was mere rhetoric, incapable of expressing the truth like philosophy could. Indeed, European acting history became bound up with the rules of classical rhetoric used by lawyers, theologians and diplomats. Stage acting came straight from the legal and political toolboxes of persuasion. The history of pretence is tied up with the history of power.

Around 350 BC, Aristotle wrote Rhetoric, his treatise on the principles of oratory. He extrapolated from Greek theatre the different techniques used on stage by the hypokritai of his day — individuals who could command the attention and emotions of large audiences — and applied them to the courtroom. Aristotle defined ten categories of emotion, that might be activated according to circumstance: Anger, Calm, Friendship and Enmity, Fear and Confidence, Shame, Favour, Pity, Indignation, Envy, Jealousy. ‘Aristotle’s principles of rhetorical delivery are explicitly derived from the best actors’ practice,’ argues theatre historian Jean Benedetti. ‘Control and command of pitch, dynamics, stress, rhythm, range, flexibility, together with appropriate body language, were essential.’ The legal advocate needed to play on emotions in order to build a persuasive argument, to pull judges onside. ‘Thus by a significant reversal, actors’ practice was enshrined in the principles of rhetoric, which then, historically, became a prescriptive set of rules for the actor.’

The Roman philosopher-politician Cicero and the rhetorician Quintilian built on Aristotle’s work. In his On the Orator, written in 55 BC, Cicero examined the relationship between bodily gestures and tone of voice; purity of diction, memorizing an argument, the most suitable words for a situation. Quintilian’s twelve-volume Institutes of Oratory, produced in the first century AD, was designed as an educational manual, leading would-be orators through the various principles of the art and the stages of training in minute detail. Having existed only in fragments for many centuries, the complete manuscript for Institutes of Oratory was rediscovered in the basement of a Swiss monastery during the fifteenth century, consolidating its status as one of the most influential texts on the subject. In the fourth century AD, following his conversion to Christianity, St Augustine of Hippo applied the principles of pagan Greek and Roman rhetoric to preaching. Augustine argued that the art of rhetoric was neutral, that it could be applied for both good and bad purposes — worn like a costume or mask, you might say — and that its powers of persuasion could be used for spreading the teachings of Christianity.

In England, stage acting had been shaped during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras by a fusion of techniques learned from classical rhetoric and by the vernacular styles of medieval mystery and morality plays. Acting in Shakespeare’s day was expansive and colourful, big enough to hold the attention of large outdoor audiences, but not without elements of naturalism. When Shakespeare’s star actor Richard Burbage died, an anonymous fan wrote: ‘Oft I have seen him leap into the grave / Suiting the person which he seemed to have / Of a sad lover with so true an eye / That there I would have sworn he meant to die.’ Theatre was banned altogether under Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth until the Stuart Restoration in 1660. Then the favoured acting style was mostly neo-classical, a highly mannered declamatory form governed by rigid codes derived from manuals of rhetoric. In French theatre of the same period, artifice and adherence to prescriptive rules of performance were placed front and centre. Deviation from those rules was strictly policed.

There was a shift during the eighteenth century, when the English actor David Garrick and his Irish contemporary Charles Macklin began to develop more naturalistic approaches to acting. Personal experience and observation of life began to influence performance, rather than bombast and affected speech. A driving force behind the move towards a more naturalistic style was Aaron Hill, editor and publisher of The Prompter. ‘The actor who assumes a character wherein he does not seem in earnest to be the person by whose name he calls himself, affronts instead of entertaining the audience…’ wrote Hill in the 13 June 1735 edition of his magazine. ‘Have we not a right to the representation we have paid for?’

Despite the influence of Romanticism on the theatre, French acting techniques remained mired in the courtly neo-classical style until the end of the nineteenth century, when writers and theatre producers — frustrated at the limited skills of their performers — demanded a naturalism that would more accurately reflect society’s problems at the turn of the century. The acting teacher François Delsarte developed a popular system that claimed to connect every conceivable emotion with a physical gesture. It was a standardized approach to body language, developed from years Delsarte spent observing human behaviour in a variety of situations. His hope was to give actors more precision in their capacity to express human experience. Through his protégé, the American Steele MacKaye, and the publication in 1885 of The Delsarte System of Expression — a handbook compiled by MacKaye’s student Genevieve Stebbins — the French teacher’s ideas spread rapidly throughout the USA. But there Delsarte’s system petrified into melodramatic, stiff forms of acting.

The Russian stage, by contrast, was revolutionized by the work of Pushkin, Gogol and the actor and director of Moscow’s Maly theatre, Mikhail Shchepkin. Their techniques of ‘psychological realism’ required a deep level of belief on the part of the actor that he was truly living the situation and character he was playing. Actors began to dispense with using recognizable sets of gestures and instead concentrate on the internal drive of a given character. Shchepkin’s ideas were eventually passed down to Konstantin Stanislavski, who developed the ‘System’. Stanislavski’s theory was that an actor could produce his or her emotional responses by fusing observations of human behaviour with personal lived experience, and feed that into their onstage character. ‘Always and forever, when you are on the stage, you must play yourself,’ says the Director in Stanislavski’s book An Actor Prepares. ‘But it will be an infinite variety of combinations of objectives, and given circumstances which you have prepared for your part, and which have been smelted in the furnace of your emotion memory.’

The Russian’s ideas travelled to the US in the 1920s. Lee Strasberg’s ‘Method’ technique, developed at the Actors Studio in New York, was an interpretation of Stanislavski that placed strong emphasis on ‘emotion memory’. (Strasberg’s colleagues Stella Adler, Elia Kazan and Robert Lewis disputed this approach.) The Method encouraged actors to physically live through the experiences of the characters they were to play. If the actor knew what it was lik...