Structure

This book is about English syntax. As explained in the Introduction, the syntax of a language is a matter of the form, the positioning and the grouping of the elements that figure in the sentences of that language. In a word, it’s about their STRUCTURE. But structure is a very general concept that applies to any complex thing, whether it’s a bicycle, a commercial company, or a carbon molecule. When we say something is ‘complex’ we mean, not that it’s complicated (though of course it may be), but that

ait’s divisible into parts (its constituents),

bthere are different kinds of parts (different categories of constituents),

cthe constituents are arranged in a certain way, and

deach constituent has a specific function in the structure.

When anything can be analysed in this way, it has structure. And it’s crucial that, more often than not, the constituents of a complex thing are themselves complex. In other words, the parts themselves have parts and these may in turn have further parts. When this is so, we’re dealing with a hierarchy of parts and with hierarchical structure.

It’s obvious, for example, that a complex thing like a bicycle isn’t just a random collection of bits and pieces. Suppose you gathered together all the components of a bicycle: metal tubes, hubs, spokes, chain, cable and so on. Try to imagine the range of objects you could construct by fixing them together. Some of these objects might be bicycles, but others wouldn’t remotely resemble a bicycle – though they might make interesting sculptures. And there would probably be intermediate cases – things we’d probably want to say were bicycles, if only because they resembled bicycles more than anything else. So, only some of the possible ways of fitting bicycle components together produce a bicycle. A bicycle consists not just of its components but – more importantly – in the structure that results from fitting them together in a particular way.

The same goes for linguistic expressions (sentences and phrases), i.e. for syntactic structure. Suppose you have a collection of words, say all the words in an English dictionary. Can you imagine the possible word-strings you could construct by putting these words together? The possibilities are endless. Clearly, not all the word-strings would be acceptable expressions of English. And, again, some would be odder than others. When a string of words is not a good expression in English, it’s said to be ungrammatical (or ill-formed). We’ll mark it with a STAR (*). For example:

[1a] *the nevertheless smiling up quickly

[1b] *disappears none girls of the students

[1c] *Max will bought a frying pans.

More subtle examples of ungrammatical strings were given in the Introduction.

Ultimately, a full syntactic description of any language will explain why some strings of words of the language are well-formed expressions and others not. This couldn’t be achieved without recognising structure. Just as the concept of structure was required in distinguishing between the bicycles and the non-bicycles, so it’s essential in distinguishing between strings of words that are grammatical expressions and those that are ungrammatical.

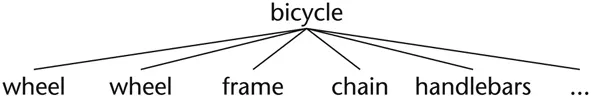

We can use diagrams to show how things are analysed into their constituents. For example, [2] says that a bicycle can be analysed into two wheels, a frame, a chain, handlebars, among other things (the dots mean ‘and other things’):

Such diagrams are called tree diagrams (though the trees are upside-down).

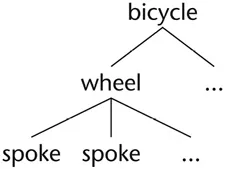

I’ve said that the constituents of a complex thing can themselves be complex. A bicycle wheel, for example. It is itself a constituent of the bicycle, but in turn consists of hub, spokes, rim, tyre, etc. Spokes are constituents of bicycles, but it’s more important to note that they are constituents of bicycles only because they are constituents of the wheel which, in turn, is a constituent of the bicycle. The relation between spoke and bicycle is indirect, mediated by wheel. We express this by saying that, although the spoke is a constituent of the bicycle, it’s not an immediate constituent of it. If we allowed that spokes were immediate constituents of bicycles, this would leave wheels out of the picture. It would imply that bicycles could have spokes independently of the fact that they have wheels.

As for the function of constituents, this too is crucial. If we represented spokes as immediate constituents of bicycles, we couldn’t specify correctly the function of the spokes. The spokes don’t have a function in respect of the bicycle directly, but only in respect of the wheels. In talking of the function of the spokes, then, we’re going to have to mention the wheels.

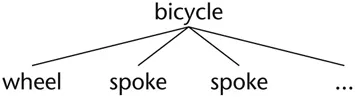

Which of the following tree diagrams best represents the structural relationship between bicycle and spoke just discussed?

Although each diagram is incomplete, the one that properly reflects the (indirect) structural relation of spoke to bicycle is [3b]. It correctly describes the relation between bicycle, wheel and spoke as a hierarchical relation. [3a] incorrectly represents spokes as immediate constituents of bicycles.

In dealing with syntactic structure, then, we’ll be doing three things: (a) analysing linguistic expressions into their constituents, (b) identifying the categories of those constituents, and (c) determining their functions. This chapter is mainly concerned with the first of these – constituency. But what kind of expressions should we begin with? I’ll take the sentence as the starting point for analysis. I’ll assume (and in fact already have assumed) that you have an intuitive idea of what counts as a sentence of English.

The first question to be asked is, ‘What do sentences consist of?’ The answer might seem blindingly obvious: ‘Sentences consist of words.’ In what follows, I’ll show that this apparently natural answer is not appropriate. In fact, the discussion of hierarchical structure quickly forces us to abandon the idea that sentences consist, in any simple way, of words.

This can be shown by asking whether the relation between a sentence and its words is direct or indirect, mediated by parts of intermediate complexity. Put another way: Are words the immediate constituents of the sentences that contain them? It’s only if the words contained in a sentence are its immediate constituents that we can allow that sentences actually consist of words. Here’s the tree diagram that represe...