eBook - ePub

Bonnie Prince Charlie

A Biography

Susan Maclean Kybett

This is a test

Share book

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bonnie Prince Charlie

A Biography

Susan Maclean Kybett

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1988, this biography was the result of 15 years research, including unearthing 70, 000 letters and documents among the Stuart Papers which had hitherto lain largely untapped. Written in many different languages, some were damaged, written in code, or unsigned and undated. Deciphering them therefore made it possible to gain a new level of insight into Bonnie Prince Charlie as a man, his relationship with his exiled father, the role played by France and the true nature of the events leading up to the bloody campaign of 1745 in which he attempted to win back the throne of his ancestors.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Bonnie Prince Charlie an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Bonnie Prince Charlie by Susan Maclean Kybett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Scottish History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

The Warming-Pan Baby

Early on Christmas morning in 1688 a fishing boat emerged from the fog-shrouded English Channel and moored at the small French port of Ambleteuse lying between Boulogne sur Mer and Calais. A tall, dark-haired man of regal bearing, wrapped in a hooded cloak against the damp chill, hurried ashore to a coach that waited to take him to Versailles for an audience with his cousin, King Louis XIV of France.

The man was James Stuart, the grandfather of Bonnie Prince Charlie. He is better known as King James VII of Scotland and as James II of England and Ireland. He had just left his three kingdoms behind because his people did not want him anymore. He had been allowed to depart without a hair of his head being harmed; a pension had been arranged for his family; and he carried a small fortune in Crown Jewels concealed underneath his cloak in a leather-bound parcel. The boatmen who ferried James down the River Thames toward the estuary leading to the French Roads saw him throw England’s Great Seal into the water, as if to symbolize that no mortal had the right to take away the kingdoms given him by God. The Seal was retrieved later by some surprised Thames fishermen, who found it glistening in the middle of their squirming catch.

Awaiting James near Paris was his beautiful Italian wife, Queen Mary Beatrice d’Este of Modena, who had escaped from London weeks before disguised as a laundress. She had hidden their infant son in a bundle of linen in order to smuggle him out of the country. It was his birth in June 1688 that had been the signal for England to rid themselves of the Stuart dynasty once and for all. This little prince was James Francis Edward Stuart, lawful heir to the throne. His royal parents were literally pushed out of Britain’s back door and into the arms of France because they were Catholics.

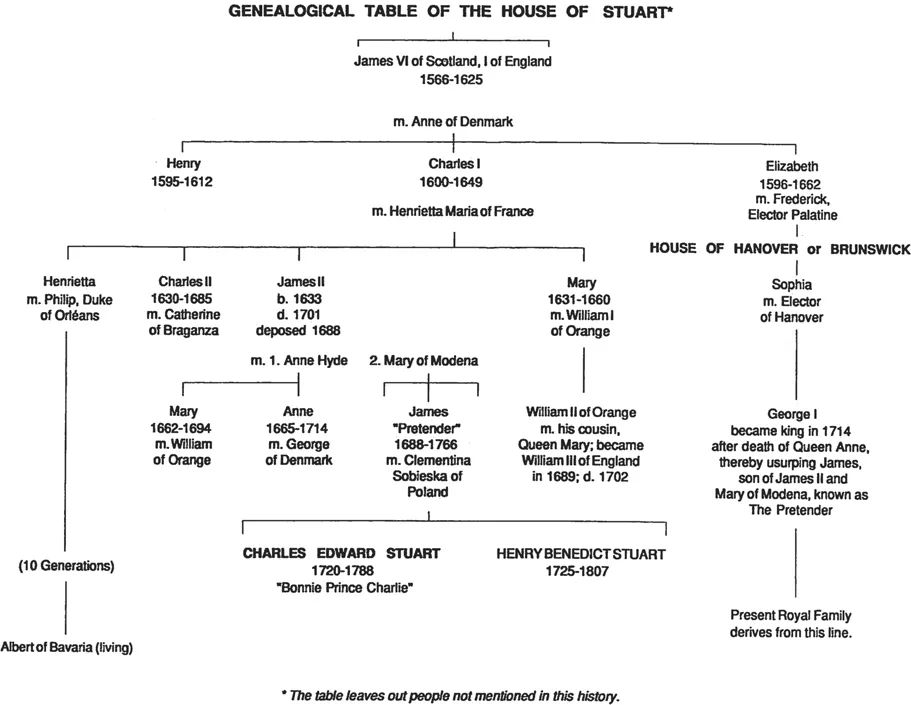

James II, as he was known in England, had not always been Catholic but had converted during the reign of his brother, Charles II (1660–85). At the time James became King, in 1685, he had been married for eleven years to Mary of Modena, his second wife. She was a devoted Catholic and twenty-five years his junior, but she had never borne him a child. She had conceived several times, but the infants were either stillborn or had not been brought to term. Therefore it was widely believed that she could not be a mother. James himself had demonstrated his fecundity on many occasions with various mistresses and had fathered several illegitimate offspring. He had also sired two legitimate daughters by his first wife, Protestant Anne Hyde. They were Mary, born in April 1662, and Anne, born in February 1665. Mary was now married to her Protestant first cousin, William of Orange, son of James’s sister and the Stadtholder of the United Dutch Provinces; Anne was wed to Lutheran Prince George of Denmark.

Because James II was fifty-two years old when he ascended the throne in 1685 and no Stuart had lived beyond the age of sixty, it was anticipated that his daughter Mary and her husband William would soon jointly rule Britain. This was a very comforting thought for the Papist-hating nation; England had pushed out the Church of Rome during the reign of Henry VIII a century and a half before. Henry had established the Church of England, and laws had been enacted that excluded Catholics from any voice in government. Henry outlawed the Catholic Church not only because he wanted a divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne Boleyn; he could easily have dispensed with his first wife as he did his later wives. Rather, it was the political aspects of the Catholic Church that Henry sought to eliminate. The Catholic Church at that time was a highly political party—far different from the institution we know today.

Henry VIII’s hatred of Catholics, which has everything to do with our story, was also based on economic considerations. Henry had to ensure England’s survival in a highly competitive world. Columbus had charted a route to America when Henry was a year old; since then, Catholic France and Spain had made great strides in conquering and colonizing territories in the New World. Little England was being left behind. A review of his nation’s wealth demonstrated to Henry that most of it was flowing into the coffers of Rome through offertories in English churches; England was in effect financially supporting the explorations of its traditional enemies. Moreover, it was the Pope’s plan to keep Britain financially subordinate to Rome.

Henry’s main objective in eliminating the Catholic Church was to use the money for an aggressive ship-building program to compete overseas with the Catholic powers. His policy was pursued even more aggressively by his daughter, Elizabeth I, and it put England on the road to greatness. However, the Catholic party had to be totally eliminated in Britain before that came to pass.

James II appeared incapable of grasping the economic reasons for Britain’s antipathy toward Catholicism (which had also been outcast in Scotland); he continued to seek out Jesuit priests for advice and counsel on affairs of state. As far as the populace was concerned, as long as William and Mary were in the wings and James II had no male heir to take precedence over them, they were prepared to wait. It was a distinct surprise, therefore, when early in December 1687 Mary of Modena announced that she was once again pregnant and expected to give birth in June.

Princess Anne disliked her stepmother intensely; she was immediately suspicious. She went to St. James’s Palace and contrived to be with the Queen as she was disrobing. She inquired if she might feel the Queen’s belly, but Mary of Modena would have none of it and withdrew to an anteroom for privacy. Anne wrote several letters to William and Mary in Holland casting doubt on the pregnancy. The Queen added fuel to the fire by frequently predicting that her child would be a son; since males took precedence, this meant that the succession would not pass to Anne’s Protestant sister Mary.

Anne was not alone in her suspicions. It was widely known that the Pope and his emissaries had done everything possible since the expulsion of Catholicism to regain a foothold in England; some suspected that a feigned pregnancy and spurious male child would be foisted on the nation to perpetuate a Catholic succession. As Anne reported to her sister in March 1688, “Her being so positive it will be a son, and the principles of that religion being such that they will stick at nothing, be it never so wicked if it will promote their interest, give some cause to fear there may be foul play intended.” Even though no fewer than twenty-nine Protestant and Catholic men and women witnessed the birth of James Francis Edward Stuart on June 10, 1688, a story swept London that the child was really the offspring of a chambermaid and had been smuggled into the Queen’s lying-in bed in a warming pan. It was several months before depositions to the contrary from those in attendance at the birth reached the public ear, but the fact remained that the English people did not want the royal succession to go to a Catholic.

The little Prince’s arrival upset much of the political machinery that had been put into place on the assumption that William and Mary would soon rule Great Britain. William of Orange was already the nominal head of the League of Augsburg, an alliance of Protestant rulers in Europe that was bent on diminishing France’s encroachment on their territories. William’s domain, Holland, was particularly threatened because of its proximity to France. His country was also bordered by the Spanish Netherlands, whose ruler, the King of Spain, was a member of the French Royal House of Bourbon. Protestant German and even Catholic Italian states, in fear of being swallowed up by the combined efforts of the French and Spanish Bourbons, also belonged to the League.

William of Orange had practically begged his Catholic father-in-law (who was also his uncle) James II, to bring England into the League to squash the two Catholic powers forever, or at least to take active steps to create an equitable balance of power in Europe. William had even been in secret correspondence on the matter with several powerful leaders of the Whig party in England who desired the same thing. But James II refused to join the League on the grounds that he wished to live in harmony with “mon cher cousin,” Louis XIV. Other considerations also blocked the King’s vision, all of them religious. The members of the League of Augsburg and the English Whigs wondered how a man could be so bereft of vision as to fail to do an action that would be politically expedient for his nation.

Almost from the moment James II ascended to the throne in 1685, he had moved like a man possessed to reverse existing laws that prevented Catholics from holding public office. He dismissed Protestant military and government leaders and appointed Catholics in their place; the number of Jesuit priests and advisers at court swelled alarmingly. James held Mass openly, which had been banned by law, and he imprisoned seven bishops of the Church of England for refusing to order Anglican clergymen to read a Declaration of Indulgence toward Catholics at every service. Crown appointments in Ireland and Scotland effectively placed Catholics in control, and although a law had been passed that communication with the Pope was treason, James sent an ambassador to Rome expressing his obedience to the Holy See. He also attempted to foist Catholic leadership on Oxford and Cambridge universities.

When he increased the ranks of the standing army without the sanction of Parliament, the populace feared that his plan was to use force to restore England to the Catholic fold. As a king, James considered himself the father of his people and responsible for saving them from the heretical path of Protestantism. He was so filled with religious zeal that he could see nothing beyond restoring the nation to the Church of Rome. Even the other Catholic monarchs, Louis XIV included, shook their heads when they realized that James Stuart was under the spell of hierarchical Jesuit wizardry.

Shortly after the birth of James Francis in 1688, a letter was delivered to the King from his ambassador at The Hague stating that William of Orange would soon be arriving in England with an army to investigate the birth’s circumstances and legitimacy. In the meantime, James II sensed a distinct coolness from political and military leaders, particularly from the Duke of Marlborough, who commanded his army.

When James heard that William of Orange had landed with troops at Torbay in Devon and was marching northeast to London, gathering recruits along the way, he tried to reach the Duke of Marlborough. But the Duke had been in league with William all the time; he took the army to join up with William at Salisbury. There he set up an encampment and waited while the befuddled James slowly faced the reality that neither he nor his Catholic heir was wanted. He sank into an abysmal stupor laced with confusion and fear. This was hardly surprising; his own father, Charles I, had been executed at Whitehall in 1649 for treasonably bringing military force against Parliament and causing civil war. His great-grandmother, Mary Queen of Scots, had also been executed after thirty years of involvement in Catholic plots against the English crown.

Therefore, James II, anticipating a similar fate, sent Mary of Modena and his son to France, disguised as a laundress and a bundle of dirty linen. The strategy behind the decision that he leave the country was that nobody wanted another Stuart martyr. James left England grateful for his life, but his pride was deeply wounded. The circumstances of his exit reinforced in himself the belief that the only true religion was Catholicism and that the British nation was made up of Protestant heretics. This lesson he later passed on to his son.

There was wild rejoicing in the streets once it became known James Stuart was gone. His daughter Mary arrived from Holland to join her husband; cheering throngs lined the processional route when they were crowned at Westminster Abbey in April 1689. Parliament announced “That King James II., having endeavoured to subvert the constitution of the kingdom by breaking the original contract between king and people, and having, by the advice of Jesuits and other wicked persons, violated the fundamental laws, and withdrawn himself out of the kingdom, has abdicated the government, and that the throne is thereby vacant.” James never did abdicate, nor did he renounce any claim to the throne. Strictly speaking, there was no foundation in law for what had happened—a fact that disturbed Protestants and Catholics alike in England, Ireland, and Scotland.

Scotland was an independent nation at that time. Many Scots refused to swear oaths of allegiance to William because he was not Scotland’s King. It was the Stuart James VI, son of Mary Queen of Scots, who had left Edinburgh in 1603 to become James I of England and Ireland when his cousin, Elizabeth I, died childless. Even before that time, it had long been the fond hope in Westminster that Scotland would join with Ireland and England to create a United Kingdom under an English king, but differences in religious philosophy—the Scots were mostly Presbyterian—and an innate desire to control their own policies had prevented a union up to that time.

Many Lowland Scots would have had no objections to a union, but the fiercely proud Highlanders living beyond the northern mountains and in the islands had no taste for government centralized in Westminster. The Highlanders had a patriarchal clan system that had been formed by centuries of inbreeding. Each clan was made up of family members bearing the same name. They were led by chieftains, little kings in their own right, who had the power of life or death over subordinate clan members. The system was feudalistic, creating many headaches for the Scottish government officials in Edinburgh who had struggled for centuries to bring cohesion to their fragmented nation.

So far, that had proved to be impossible because the Highlanders were a law unto themselves. Situated beyond impenetrable mountains and wild seas, they settled internecine feuds locally, with no interference from Edinburgh. Each time a chieftain felt pressure to conform from Edinburgh or London, he resorted to claiming no other Liege Lord but the lately departed James Stuart. It was mere strategy; at heart many had no liking for the man at all. Whatever their motives, they became known as Jacobites, “followers of James,” from his Latin name, Jacobus.

Ireland, with its large population of Catholics, was the scene of the first and most vociferous Jacobites. Their outrage at the dethroning of the lawful hereditary king was based on religious rather than political grounds and on extreme resentment of and anger at England’s attempts to “pacify” Ireland. Catholic Ireland had been the number-one target for pacification when England expelled Romanism. One reason for this was that her ports could be invaded by the Catholic powers; Ireland thus was the weakest link in England’s defenses. She had to be subdued if Protestantism were to survive. It was to Ireland, then, that James looked as a means to restore him to his rightful place on the throne.

A year and a half after James’s flight from England, King Louis XIV financed the first Stuart restoration attempt. He provided fourteen ships of the line, weapons, and thirteen hundred officers and soldiers for a landing at Kinsale in Ireland, to be led by James. On the surface the Sun King’s interest in the Irish campaign seemed to be support for the Jacobites, but in reality he was planning a naval strike against William of Orange and the Grand Alliance (successor to the League of Augsburg), which now included England as a member. Louis’s stratagem was to use James to create a disturbance in Ireland to divert British forces from the area of the intended French attack.

At first, all appeared to go well for James in Ireland. By far the majority of cities declared for him, and he was able to recruit enough Irishmen to bring his army to thirty thousand men. But there were problems: the arms and artillery brought from France were woefully inadequate, and the countryside was practically devoid of weaponry due to earlier pacification attempts. In addition, food and money were scarce. When William arrived in June 1690 with a composite army of English, German, and Dutch troops totaling thirty-six thousand, James’s army was quickly demoralized. In the ensuing Battle of the Boyne (July 1), most of the footsoldiers fled without engaging in battle, and the victory went overwhelmingly to William of Orange. Some twelve thousand people took advantage of the offer to leave their native land to relocate in France and Spain at England’s expense.

The Stuarts’ residence in exile donated by Louis XIV was the Chateau of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, about twelve miles west of Paris, overlooking the Seine. As if to give the lie to the warming-pan story, Mary of Modena gave birth to a second child in 1693. She was a charming little princess named Louise Marie, but she was unfortunately carried off by smallpox in 1712. Young James Francis was brought up in a solitary fashion by backward-looking tutors who schooled him thoroughly in languages; their view of life favored the King’s view that the destiny of the Stuarts was to uphold the aims of the Catholic Church. James himself took a hand in schooling his son in deportment; how to walk like a king, how to posture majestically, and how to arrange his facial features so that the beholder would fall on bended knee in adoration of God’s anointed. No one was allowed to speak unless first addressed by the Prince, who was counseled to speak only to his immediate retainers. Later, James Francis schooled his own son in exactly the same way. It was a comedic farce in view of the fact that the Stuarts had no country to rule.

In the meantime, William of Orange and the Grand Alliance waged war against Louis XIV for eight long years, greatly diminishing the once-healthy French treasury and almost bringing France to its knees. Mary of Orange died childless of smallpox in 1694 at the age of thirty-two, and William was left to rule alone. Princess Anne was next in line.

Anne was an unintelligent, mean, and malleable woman greatly addicted to gambling and laudanum, the opium-based drug of the day. But her woeful obstetric history was of greatest concern. Out of at least nineteen attempts at motherhood, most of her pregnancies had ended in miscarriage or stillbirth. Her only living child, a son, was pathetically frail and diseased. Thinking ahead about the succession, William opened up a correspondence with the father-in-law he had usurped, stating that he would be willing to name young James Francis heir to the throne if the boy were reared as a Protestant.

William earned Anne’s everlasting hatred when news of the plan reached her ears. And when James II and Mary of Modena received William’s proposal at Saint-Germain, they were enraged at his diabolically heretical suggestion. Even if religion had not been involved, James would never agree to relinquish his own rightful title and thereby set a legal precedent that would forever threaten the prerogatives of his descendants. Nor could he stomach such an outrageous offer from the son-in-law who had plotted to take his place.

By 1697, Louis XIV was more than ready to call a halt to the war with England. He signed the Treaty of Ryswick, by which he was required to officially recognize William as the legitim...