![]()

POLITICAL MODERNISATION: WEAK AND AUTHORITARIAN STATES

“You know what? These policeman are going to beat you until nightfall, when they will return home to eat and sleep. And then other policeman will arrive and will beat you until sunrise, when the first policemen will come into work and beat you until nightfall. Compared to us you’re nothing. We are the government. Would you like to return to your family? Your mother and father must be worried about you...”

(Alaa Al-Aswany, The Yacoubian Building)

“System? What system? I am the system!”

(Habib Bourguiba, President of Tunisia)

“Where there is no tax, there is no need for representation. In the Middle East there is no need even for a population, which simply reduces the oil wealth of those who control them. Why share this income with a population they do not need? Why look after their safety? Why inform them? Why cultivate them? Why employ them? The Arab masses must be consolidated, stabilised, controlled and maintained on an income of between one and two euros per day.”

(Jana Hybášková, Ambassador of the European Union in Iraq)

“I got to know another Morocco. A Morocco of poverty, shame and desperation. Examinations in the state hospital were free, but we had no drugs.”

(Tahar Ben Jelloun, The Last Friend)

“We do not reject America, but we have the feeling that America is rejecting us. This isn’t about envying America but more the feeling that we are hated by America. We want to be recognised and respected by America. But we feel that this isn’t the case. We feel like rejected lovers.”

(An Educated Lebanese)1

Although national service did not officially exist in Morocco at the end of the 1960s, barracks in the Sahara operated as boot camps for opposition-minded students flirting mainly with Marxism. In one of them, Sergeant Major Tadla, a bald, semi-literate ogre, welcomed new “conscripts” with the following words: “I’m in charge here. I report to no one, not even the camp commander. You are just ninety-four spoiled kids. You’re being punished. You wanted to be smart-asses, and I’m going to teach you a thing or two. There’s no daddy and mommy here. You can yell all you like, nobody will hear you. In this place, I will dress you and change you. You’ll no longer be spoiled kids, queers, children of the rich. Here Commander Tadla rules. Forget all that liberty-democracy crap. Here the slogan is: ‘We belong to Allah, our king, and our country.’ Repeat after me...” This is how the Moroccan writer Tahar Ben Jelloun evokes the authoritarian character of his country in the novel The Last Friend (2011: 87), a country that, as well as repressing its population, does not even respect its own rules and laws, while resorting to religion as the source of its own fragile legitimacy.

Modernising Middle Eastern societies continue to be governed by weak yet authoritarian regimes that over the last fifty years have barely changed, are ideologically burnt out, and are consequently incapable of co-opting newly emerging political actors. When I speak of rigidity and the stagnation of political systems, I am referring to the rigidity and stagnation of their structural parameters, which relates to the ability of regimes to survive, the ongoing preponderance of authoritarianism, and the low capacity over the long term of Middle Eastern states to govern effectively in their territory and to carry out the basic functions for their populations. Within the framework of these relatively unchanging political structures there are of course fascinating activities being played out on the part of politically relevant actors. However, the given structures do not have to take these into consideration and so certain patterns of behaviour are more probable than others. For instance, political regimes are willing to change almost everything in order that the political order remains the same and the political elites retain their power. They co-opt a minority while attempting to control, discipline or suppress the rest of the population.

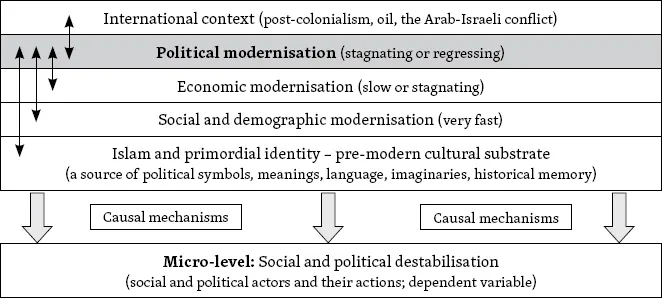

In this chapter I shall examine the mechanisms by which an interaction takes place between corrupt Middle Eastern political systems and the Islamic political imaginary. I shall also look at the mechanisms that lead to conflict between these rigid political systems and the far more dynamic demographic and social developments taking place in the region, as a consequence of which these regimes and their cronies are becoming increasingly alienated from the rest of the population. The aim of this chapter, therefore, is not only to analyse the prevalent character of political regimes in the Middle East, but above all to examine the complex, agonistic interaction of this political system with other dimensions of the uneven modernisation process and its broader context (as played out in culture and on the international stage). This objective is shown in fig. 5.

Fig. 5 The interaction of the political system with other independent variables examined in this chapter

N.B. Possible interactions and tensions are shown by the arrows.

FROZEN POLITICAL MODERNISATION IN AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON: THE DEMOCRATIC DEFICIT

When we think of repressive regimes, what countries spring to mind? Russia, controlled by elites drawn from the secret services, the mafia, and gas company oligarchs? China, where a billion people are controlled by the million-strong caste of the communist party? Communist Cuba, bankrupted and crushed by economic sanctions? Belarus, over which the European Union is forever wringing its hands? Or famine-struck, fortress-minded North Korea? These regimes certainly have their problems. However, there is a blank space in our mental map where the West has long overlooked, downplayed or even justified repression in the name of preserving stability: the Arab world.

According to the democracy index published by The Economist (Democracy Index 2010), Kuwait, Morocco and Jordan are even more repressive than Russia (see table 1). However, they are long-term strategic allies of Washington in a geopolitically key region, and so the West conveniently ignores the undemocratic nature of these monarchies and, on the contrary, offers them support.

Similarly, the much maligned Cuba is actually slightly more democratic than the pro-American regime of Bahrain, where an American naval fleet has been based since 1971. The minority Sunnis have long persecuted the majority Shiites, who have been deprived of their political rights and a share in the country’s oil wealth. In 2011, with fraternal Sunni military assistance provided by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain massacred demonstrators calling for fairer treatment and democratisation. Likewise, communist Cuba is a freer place to live than the military dictatorship in Algeria supported by France, where in 1991 the army annulled the results of democratic elections won by the opposition Islamic Salvation Front, so plunging the country into civil war (1991–1997).

Table 1 Democracy Index: The Middle East and comparable countries 2015

Country | Overall ranking out of 167 countries evaluated | Final score and description of regime |

Israel | 34 | 7.77 (flawed democracy) |

Tunisia | 57 | 6.72 (flawed democracy) |

Turkey | 97 | 5.12 (hybrid regime) |

Lebanon | 102 | 4.86 (hybrid regime) |

Morocco | 107 | 4.66 (hybrid regime) |

Palestine | 110 | 4.57 (hybrid regime) |

Iraq | 115 | 4.08 (hybrid regime) |

Mauretania | 117 | 3.96 (authoritarian regime) |

Algeria | 118 | 3.95 (authoritarian regime) |

Jordan | 120 | 3.86 (authoritarian regime) |

Kuwait | 121 | 3.85 (authoritarian regime) |

Bahrain | 122 | 3.49 (authoritarian regime) |

Comoro Islands | 125 | 3.71 (authoritarian regime) |

Qatar | 134 | 3.18 (authoritarian regime) |

Egypt | 134 | 3.18 (authoritarian regime) |

Oman | 142 | 3.04 (authoritarian regime) |

Djibouti | 145 | 2.90 (authoritarian regime) |

United Arab Emirates | 148 | 2.75 (authoritarian regime) |

Sudan | 151 | 2.37 (authoritarian regime) |

Libya | 153 | 2.25 (authoritarian regime) |

Yemen | 154 | 2.24 (authoritarian regime) |

Iran | 156 | 2.16 (authoritarian regime) |

Saudi Arabia | 160 | 1.93 (authoritarian regime) |

Syria | 166 | 1.43 (authoritarian regime) |

Selected predominantly Muslim countries |

Indonesia | 49 | 7.03 (flawed democracy) |

Malaysia | 68 | 6.43 (flawed democracy) |

Bangladesh | 86 | 5.73 (hybrid regime) |

Bosnia and Herzegovina | 104 | 4.83 (hybrid regime) |

Pakistan | 112 | 4.40 (hybrid regime) |

Afghanistan | 147 | 2.77 (authoritarian regime) |

Regimes most criticised by the West |

Burma | 114 | 4.14 (authoritarian regime) |

Cuba | 129 | 3.52 (authoritarian regime) |

Belarus | 127 | 3.62 (authoritarian regime) |

Russia | 132 | 3.31 (authoritarian regime) |

China | 136 | 3.14 (authoritarian regime) |

Uzbekistan | 158 | 1.95 (authoritarian regime) |

Turkmenistan | 162 | 1.83 (authoritarian regime) |

North Korea | 167 | 1.08 (authoritarian regime) |

Selected Western democracies |

Norway | 1 | 9.93 (full democracy) |

United States of America | 20 | 8.05 (full democracy) |

Italy | 21 | 7.98 (flawed democracy) |

N.B.: The Economist’s Democracy Index ranks countries from 10 (democratic) to 1 (authoritarian). Ranked in descending order.

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2015

One might, for instance, compare China, long subject to criticism, with the degree of repression in Qatar and Egypt. Since the 1980s, Egypt has been receiving financial, military and food aid from the United States every year in exchange for peace with Israel and calm operations in the geopolitically strategic Suez Canal. The authoritarian states of Oman, United Arab Emirates, Tunisia and Yemen are considerably less democratic than China.

Finally, Saudi Arabia, constantly pampered and protected by the Americans and possessing the largest oil reserves in the world, has long been the least democratic Arab state of all. Along with North Korea, Turkmenistan and Burma it is the most repressive state in the world, less free even than the endlessly criticised Iran. The Saudi regime has no respect for human rights. No opposition whatsoever is permitted in the country. School textbooks are crammed full of intolerance and hatred for otherness. Not only the representatives of other religions are persecuted (Christians and Jews), but even Muslims simply professing a slightly different concept of Islam (including Shiites). The large numbers of foreign workers in the country are treated almost like slaves, women are subject to discrimination, and torture in prisons is rampant. Mutilation as a penalty is still practiced, including the medieval punishments of flogging, stoning or decapitation by sword (Human Rights Watch 2010).

Middle Eastern societies that in most respects are modern and undergoing rapid transformation are ruled by “archaic” political systems that have remained virtually unchanged for the last half century (Roy 1992). Even before the arrival of Islamists on the political scene, these regimes were incapable of co-opting newly emerging political actors and regulating the conflicts of interest groups (Lerner 1964). It was the slow pace of change in the political subsystem, which lags behind the rapid changes taking place in other spheres, which became the source of destabilisation and tension in the region. Middle Eastern regimes are praetorian: they exclude political actors from the system, exiling them to the street and illegality. The fact that the politically mobilised masses are unable to participate legally in politics leads to a higher incidence of political violence (Huntington 1968).

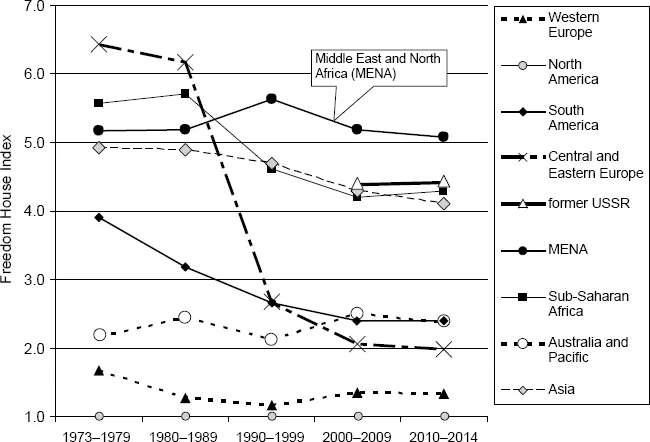

Fig. 6 Development of political rights and civil liberties in global macro-regions 1973–2015

NB.: The author’s calculation of the arithmetic average of individual macro-regions (unweighted by the population size of particular states). This is a synthetic index. It is the arithmetic average of indices measuring civil liberties and political rights. Turkey is included in Western Europe and Israel in the MENA region. The Freedom House index ranks individual countries from 1 (a democratic, free country) to 7 (not free).

Source: Freedom House

The Middle East has long been the least free and democratic macro-region in the world. Conversely, Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, Latin America and post-communist Europe are these days incomparably more democratic (see fig. 6 and table 1). In terms of established politological typologies we can divide Middle Eastern regimes into secular republics where the president occupies a privileged position (Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Algeria, Egypt, and Tunisia up until 2011), and republics combining secular and re...