![]()

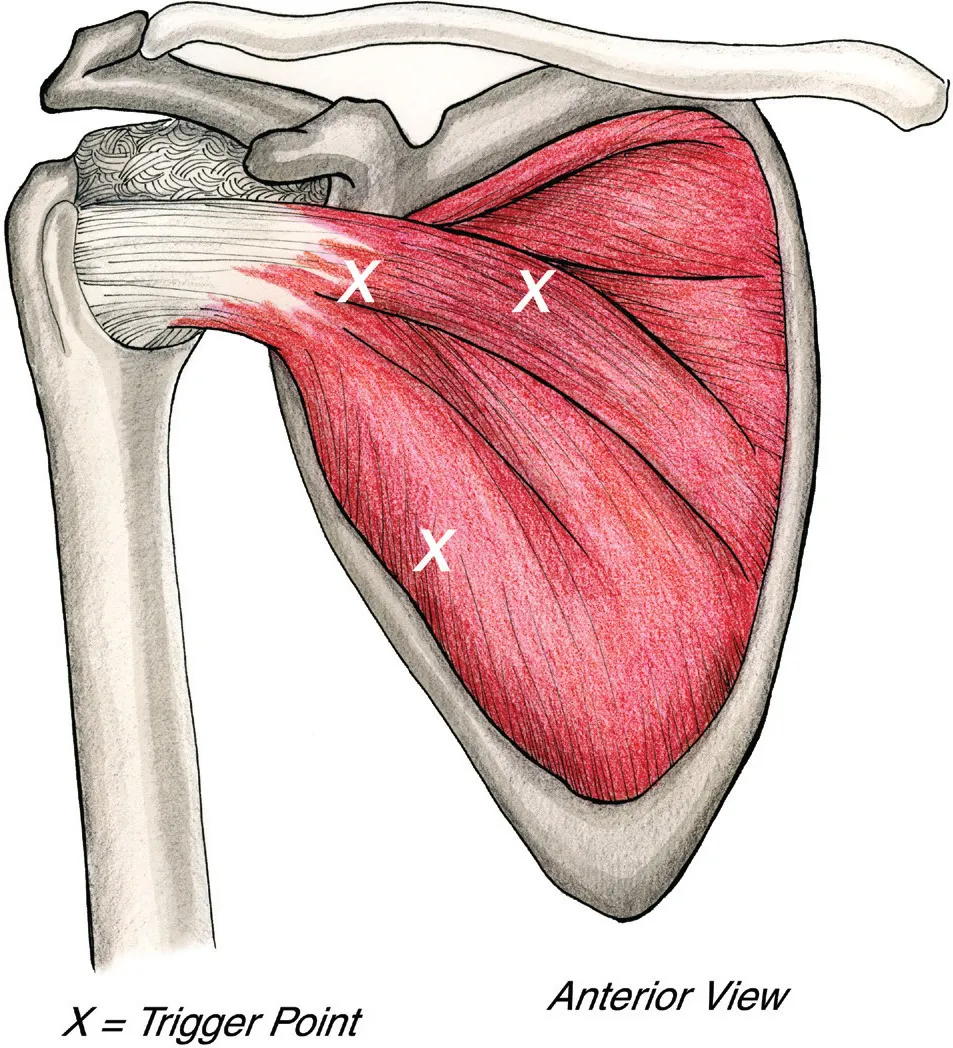

The following pages present techniques and protocols for releasing the rotator cuff and surrounding musculature. The X’s on the drawings represent the most common sites of trigger points, although I have found trigger points can be anywhere. These techniques and protocols are “a way” not “the way” and are there to serve as guidelines or trail markers. The muscles do not have to be worked in the order presented. It’s practical to do all your supine or prone work at the same time. Do stretch the muscle after you work it. This is when the muscle is most responsive. Each client is unique and presents us with creative challenges in the use of our skills, intuition and knowledge. Neck problems contribute to shoulder problems, therefore it is wise to release the neck before beginning the shoulder work. Expand and enlarge upon the following techniques and protocols with your knowledge and creativity. Know the actions and attachments of the muscle you are working. A strong foundational knowledge of anatomy is indispensable for intelligent, intuitive bodywork. Below are a few images or sayings I think about when doing bodywork:

♦Dance with the muscles!

♦Combine working two muscles at the same time. Since all muscles work interdependently, especially the rotator cuff, this is an especially effective release technique.

♦Work the muscle in a shortened state, a neutral state, and a stretched state.

♦Tire the muscle, don’t tear it!

♦How can I do this more softly? (Not necessarily less pressure)

♦Allow your fingers to “swim” gently and deeply through the tissue layers.

♦Experiment with traction and compression while working the muscles.

♦Breath connects us all! Breathe deeply while working and encourage your client to do the same.

♦Practice patience, non-judgment, curiosity, and compassion.

♦If it hurts you, don’t do it! Adapt the technique to suit your body.

♦Feel before acting and follow the cues of the client.

♦The healer in you contacts the healer in your client.

♦Save your hands! Use tools. Small hot stones are wonderful, especially for the small supraspinatus.

![]()

SUBSCAPULARIS MUSCLE

Actions: internal rotation of the humerus at the shoulder joint and stabilization of the head of humerus in the glenoid fossa. Also assists in adduction of the humerus. Attachments: medial border of the anterior surface of the scapula and the lesser tubercle of the humerus.

The subscapularis is a thick muscle with a broad tendon which covers the anterior scapula and reinforces the shoulder joint. It functions to stabilize, internally rotate, depress and adduct the humeral head in the glenoid fossa. Attachments are the medial border of the anterior surface of the scapula and the lesser tubercle of the humerus.

This sturdy muscle provides 50% of the strength of the rotator cuff. Subscap plays a vital role in joint centration, depressing the humeral head, along with the other rotator cuff muscles, during abduction of the shoulder joint, counteracting the powerful force of the deltoid. Weakness, or as I like to think of it, disruption of its ability to function at full capacity, can lead to anterior glide syndrome, as the larger internal rotators drive the humeral head anterior, which often leads to impingement syndrome. Another important function of subscap is its eccentric activity, protecting the shoulder joint during external rotation.

The scapula rests on the serratus anterior and subscap, which move across one another as the scapula moves so working on these muscles assists the scapula to glide on the thorax.

The shoulder joint follows the scapula. Increasing scapula stability and mobility leads to increased glenohumeral joint function. Skilled comprehensive work on subscap is essential for recovery from rotator injuries.

Trigger points the refer across the shoulder blade, down the arm, and around the wrist.

PALPATION

In my workshops I’ve discovered that approximately 80% of therapists thought they were on subscap, but were on latissimus dorsi/teres major. It’s an easy mistake to make and easily correctable. The reason for this common error is that therapists attempt to enter subscap too far inferiorly. If you do that the ribs will block you and you will mistake the fat lat for subscap.

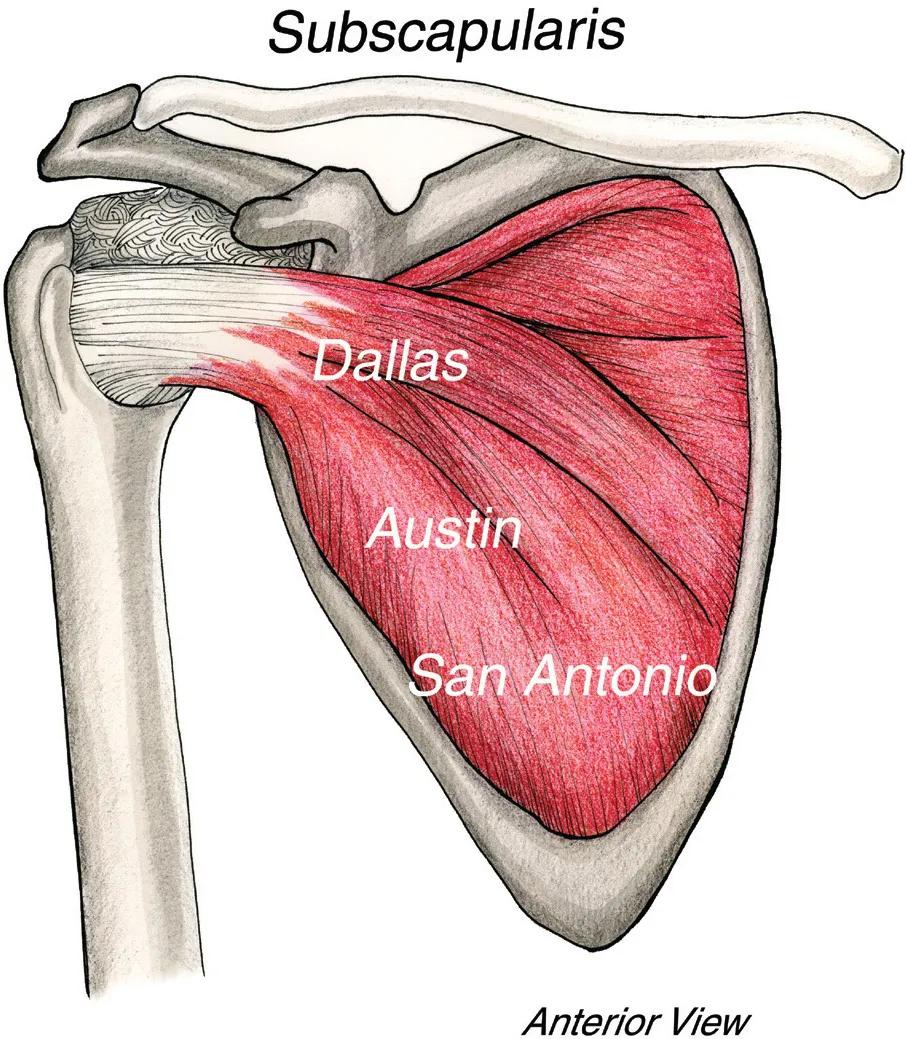

The best place to enter subscap territory is the central portion of the muscle. Bear with me while I use this analogy. I live in beautiful Austin, which is in central Texas. Dallas is north and San Antonio is south. If I try to enter subscap in the San Antonio area, I’ll most likely mistake latissimus dorsi for subscap. If I enter in the Dallas area, I’ll probably hit the tendon, which is fine if that’s where I want to start. I prefer to enter through Austin, which puts me in the less sensitive central belly and I can glide superior or inferior from there. (That’s assuming the client’s scapula is not super-glued to the thorax, which it often is. More about that later.)

Staying with this analogy, substitute your cities for mine. Begin your entry into subscap from your city. Dive under pec major with your fingers to get your medial placement first and only then gently press your finger tips toward the scapula. The medial placement is crucial, pressing posteriorly too soon causes the fingers to slide laterally and you’ll wind up on lat.

Verify your location by sliding your fingers laterally to feel the lateral border of the scapula. If you are lateral to the lateral border of the scapula, you are on latissimus/teres major, not subscap. Your mantra is: To accurately palpate subscap your fingers must be medial to the lateral border of the scapula!

STRATEGIES FOR WORKING WITH SUBSCAP

It’s all about the principles! “As to methods there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles is sure to have trouble.” (Harrington Emerson)

I think of subscap as the psoas of the shoulder because of its sensitivity, t...