![]()

CHAPTER ONE

UNDERSTANDING SUICIDE

Who Is Dying of Suicide (and Why)?

In 2019, K. Sujatha Rao, the former health secretary of India, caused a minor Twitter storm with her cryptic tweet saying ‘1 needs 2 be alive 2 be a patriot’ (sic). She was referring to our political and policy priorities, which focus on issues of terrorism while neglecting the bigger killers—communicable and non-communicable diseases. When one moves the lens on to mental health to have a closer look it is clearly evident that this policy level neglect is further magnified. We got a peek into this neglect at the highest levels of government through the eyes of Ms Rao when she reminisced about her stint in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. ‘I’ve worked in the Ministry of Health from 1988 onwards; from 1988 to 1993, I was director and Joint Secretary; and then from 1998 to 2003, and again from 2005 to 2010 I was Joint Secretary. In all those years, I had never heard of mental health, it was really not at all a priority or a concern for the Ministry of Health. Every Monday, we would have a meeting with the Secretary of Health… and that’s where the priority and high priority issues would be discussed. So, that I think would reflect on what really is a priority for the government at that time, and mental health was never mentioned. And so I really had no idea about mental health, I can’t even recall which Joint Secretary dealt with it. Mental health really struck me as one of the most important areas that Ministry of Health should have been long engaged in.’

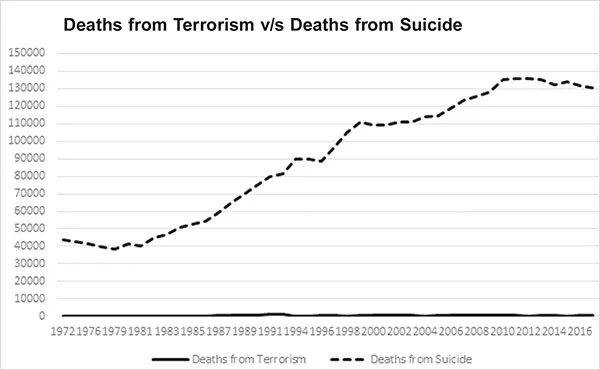

Ms Rao’s assertion of misplaced priorities is certainly backed by data when we focus on suicide. The figure below compares the trend of deaths from terrorism and suicide in India over the years. Needless to say, the latter far outnumber the former. Now let us foreground that against the policy response through the most basic metric of budgetary spending. India’s public health expenditure (sum of central and state spending) has remained between a meagre 1.2 per cent to 1.6 per cent of GDP between 2008–09 and 2019–20. Having established the size of the problem through broad-brush strokes, let us now try to understand some of its finer nuances.

As our society gradually becomes open to talking about suicide, the language associated with it is also becoming increasingly frequent in our regular conversations. This has invariably led to people using technical terms in an idiosyncratic manner. So, before we forge ahead, let us try to understand the concepts that we are going to come across frequently throughout the course of this book. This clarity is crucial, as vague and inconsistent use of terms and definitions will hinder our understanding of the complex phenomenon that we are trying to disentangle. Furthermore, it is important to have an accurate understanding of commonly used (and misused) terms such as ‘suicidal behaviour’ or ‘self-harm’, occurrence rates, functions, and clinical features.

Source: ADSI Reports of Previous Years. NCRB. Accessed 25 October 2021. Available from: https://ncrb.gov.in/en/adsi-reports-of-previous-years, and; Deaths from Terrorism, 1972 to 2017. Our World in Data. Accessed 25 October 2021. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/fatalities-from-terrorism?tab=chart&country=~IND

Suicide: Death caused by self-directed injurious behaviour with an intent to die.

Suicide attempt: Non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behaviour with an intent to die.

Suicidal ideation: Thinking about, considering, or planning suicide.

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI): Self harm performed without intent to die, usually to temporarily relieve overwhelming negative emotion, and sometimes in an effort to avoid suicidal urges

Terms such as completed suicide, failed attempt, non-fatal suicide, successful suicide, suicidal gesture, and suicide threat should be avoided as they are pejorative, misleading, and promote stigma.

The term ‘committed suicide’ conveys shame and implies that the person who died perpetrated a crime. A better and more acceptable phrase to use is ‘died by suicide’, as it is an outcome of an underlying internal or external condition(s).

Suicide and the World1

A question about the commonest causes of death evokes responses such as HIV-AIDS or ‘heart attack’. The former is an example of a disease that we ‘catch’ because of a bug and the latter is something we commonly get because of our modern lifestyle. Suicide is not the first (or even the tenth) cause that comes to people’s mind. This is surprising considering that it is among the top twenty leading causes of death worldwide. In fact, it causes more deaths than other health conditions that we worry about such as malaria, HIV/AIDS, and breast cancer. And, it certainly causes more deaths every year than issues that generally dominate news coverage, such as war and homicide. Putting it starkly in numbers, worldwide, approximately 800,000 people die by suicide every year. That is more than the population of Iceland, Bhutan or the Maldives! And when one considers the ripple effect of the suicide on other people, the already high numbers become mind-boggling.

There would be none better than Dr Shekhar Saxena, Professor of the Practice of Global Mental Health at the Department of Global Health and Population at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, to shed more light on the enormity of the challenge. Having served as the Director of the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse at the World Health Organisation, he has a bird’s eye perspective of the issue and he says, ‘For each death by suicide, there are 20 who attempt suicide. For each person dying of suicide or attempting suicide, there are at least 20 people who are affected; these could be family members, could be colleagues of friends. So we’re talking about hundreds of millions of people who are affected by suicide in one way or the other. This is indeed a huge public health issue.’

Scratch under the surface of these mind-boggling numbers and what we find is a complex picture with variations influenced by individual characteristics (e.g., gender, age) and broader contexts, such as where people live. Overall suicide rates are 1.8 times higher in men than in women. Only in a handful of countries do we find suicide rates which are higher in women than in men—namely, Bangladesh, China, Lesotho, Morocco, and Myanmar. In most of the developing world, however, the ratio is almost equal. On the other hand, in the socioeconomically richer countries of Europe and North America this ratio is nearly 3:1, i.e., three men die by suicide for every woman dying of suicide. So, quite clearly this difference is not driven solely by gender but also influenced by the macroeconomic context.

Alarmingly, 79% of overall deaths by suicide, and 90% of deaths due to suicide in adolescents occur in the developing world. After road injury, suicide is the second leading cause of death in 15–29-year-olds and third leading cause of death in 15–19-year-olds. Among 15–19-year-old girls, it is the second leading cause of death after maternal conditions and the third leading cause of death among 15–19-year-old boys after road injury and interpersonal violence.

About 10 out of 100,000 people across the world die of suicide each year. However, this number varies between countries, from less than five to more than 30. Suicide rates in Africa, Europe, and South East Asia are higher than the global average, and the lowest suicide rates are in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Furthermore, suicide is one of the top ten causes of death in eastern Europe, high income Asia Pacific, Australasia, central Europe, and in high income North America. A closer look uncovers considerable variation beneath these regional patterns. For example, the rate of suicide in South Korea in high income Asia Pacific, Indonesia in South East Asia, and Lesotho and Zimbabwe in Africa are higher than other countries in those regions and thus strongly influence the regional averages.

Just as there are geographical variations, a closer look at time trends also demonstrate complex variations. In the period between 1990 and 2016, the mortality rate from suicide increased in some countries, with the largest increases occurring in countries such as Zimbabwe, Jamaica, Paraguay, Zambia, and Belize. But the picture is not bleak across the entire world. In that same period, there have been significant reductions in mortality rates in several countries—the largest reductions occurring in China, Denmark, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Maldives, and Seychelles. Finally, despite the significant reduction in mortality rates in China, deaths from suicide in China and India together constitute 44% of global suicide deaths.

In summary, these patterns indicate that when it comes to suicide across the globe there is a complex interplay of factors, across time and geography. These include some that we have highlighted above (e.g., sociodemographic and sociocultural factors, levels of economic development), and others (e.g., unemployment, exposure to violence or use of alcohol and drugs, access to means of suicide, and patterns of mental illness) that we will tackle here and later in this book. Hence, treating it purely as a mental health issue would be missing the proverbial forest for the trees. The reality is that suicide is a multidimensional issue with complex interactions between a range of social, cultural, psychological, and biological domains.

India and Suicide

Can we trust the data?

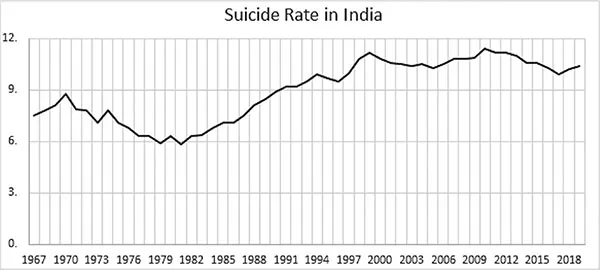

Usually, unnatural deaths in India are reported to the police. The police investigate the death and based on the evidence collected, and sometimes the autopsy report, they put together a First Information Report (FIR), which states the apparent cause of death. These FIRs are provided to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), which has been publishing annual reports on suicides since 1967. The NCRB’s reports show an increased suicide rate per 100,000 of the total population from 6.3 in 1978 to 8.9 in 1990, rising between 2006 and 2011, to 11.25, finally stabilising around 10 between 2015 and 2019, and then rising back up to 11.3 in 2020.

Although the NCRB records are the ‘best’ national level data that we have for suicide, they are beset by several problems. First and foremost, they are dependent on community reports and civil registration systems, and the former can be unreliable and latter inefficient. This is further complicated by the under-reporting of suicide due to accompanying legal consequences and social stigma. Until recently, attempting suicide was a criminal offence in India. The archaic Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) clearly states that any suicide attempt shall be punished with simple imprisonment for up to a year or with fine or both. The fear of punitive action and added hassle of having to deal with police and courts often results in refusal to seek help, which in turn means that the recorded numbers are not a reflection of the truth. There has been an attempt at the decriminalisation of suicide (more details in Chapter 8) through the Mental Healthcare Act (2017) which presumes that the individual who attempted suicide to be suffering from a mental illness unless proven otherwise and seeks to provide them with care, instead of subjecting them to criminal prosecution. Despite this attempt at decriminalisation, the social stigma associated with suicide results in the NCRB grossly under-reporting the true numbers of suicide. Some of the anticipated social consequences that lead to under-reporting include difficulty in getting married and ostracization of the individual and their family.2

Source: ADSI Reports of Previous Years. NCRB. Accessed 25 October 2021. Available from: https://ncrb.gov.in/en/adsi-reports-of-previous-years.

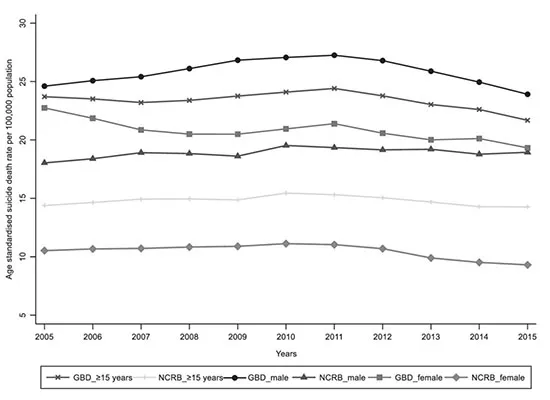

On an average, the overall suicide death rate in India reported by the NCRB was 37% lower per year compared with the rates reported by Global Burden of Disease (GBD).3 This simply means that for every 100 deaths by suicide in India only 63 get reported through the NCRB. Among men, the average under-reporting was 27% per year, and among women, the average under-reporting was as high as 50% per year. As always, P. Sainath, Ramon Magsaysay Award winning journalist who has written extensively on structural inequities in our society, pulls no punches when he addresses this issue of under-reporting. For him, it is a simple matter of wrongly registering suicide data to hide it. He says, ‘Essentially, what the NCRB are having to do is to find different places to park the corpses. And you know, anyone who works with data knows that the ultimate burial ground is a column called Others.’

The figure below is a stark representation of how the NCRB numbers are grossly lower than the GBD numbers.

Age standardized suicide death rate per 100,000 population

Source: Vikas Arya et al. J Epidemiol Community Health 2021; 75:550-555.

Despite the under-reporting, and the limitations of research studies of suicide in India, the available data offers several insights into the nature and magnitude of the problem in India. In the subsequent sections we will try to understand some of this evidence, but always keeping in mind that it is not without its limitations. We will use two studies, one a global initiative and the other a national effort, as case-studies to examine some of the nuances of suicide in India.

The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2016, is an important global initiative that estimated the burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors using data from multiple sources. As a part of that initiative, the India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative examined the trends of diseases, injuries, and risk factors from 1990 to 2016 for every state of India.

The evocatively named Million Death Study (MDS)4 from India is one of the largest studies of premature mortality in the world. Like most low- and middle-income countries, the majority of deaths in India occur without medical attention and at home; and hence these deaths do not have a certified cause. To overcome this major gap in understanding of causes of death in India, the Registrar General of India launched the MDS which monitored 14 million people in 2.4 millio...