eBook - ePub

Complications in Neurosurgery E-Book

Anil Nanda

This is a test

Share book

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Complications in Neurosurgery E-Book

Anil Nanda

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Learn from key leaders in the field of neurosurgery with the practical guidance presented in this first-of-its-kind resource. Complications in Neurosurgery uses a case-based format to explore complications across the full range of commonly performed neurosurgical procedures. As you review dozens of up-to-date, real-life cases, you'll become better equipped to identify pitfalls ahead of time and have the knowledge to handle difficult situations that arise during surgery.

- Presents commonly encountered cases provided by experienced neurosurgeons in all areas of this challenging specialty.

- Includes high-quality photographs, images, and dynamic video to ensure complete visual understanding of the procedures.

- Uses a consistent, easy-to-read format throughout, covering a wide range of surgeries including general neurosurgery and cranial complications, as well as spinal and peripheral complications.

- Numerous videos depict possible complications for each type of surgery; for example, Complications of Cerebral Bypass Surgery includes videos showing how to obtain venous hemostasis without risking injury to the STA, how to manage atheroma within the donor vessel, and how to manage intraoperative occlusion of the bypass.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Complications in Neurosurgery E-Book an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Complications in Neurosurgery E-Book by Anil Nanda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Neurosurgery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

NeurosurgerySection 1

General Neurosurgery

1

Historical Perspective

Bhavani Kura, Anil Nanda

If a physician make[s] a large incision with the operating knife, and kill[s] him, or open[s] a tumor with the operating knife, and cut[s] out the eye, his hands shall be cut off.1

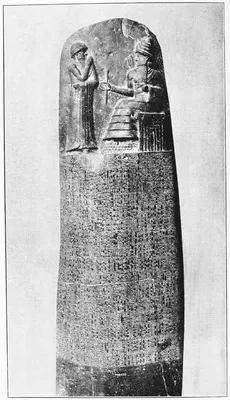

This is one of the 282 laws that constitute the Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian king who ruled from 1792 to 1750 BC (Fig. 1.1). His decrees were inscribed on a stone pillar after his rule, and several of his rulings pertained to the practice of medicine, including the enacting of a heavy penalty for a surgical complication. It is a wonder that anyone would choose to perform surgery with such a possibility at a time when morbidity and mortality likely were very high. This punishment was still less severe than that of being caught committing theft, for which the penalty was death.1

Fig. 1.1 The Code of Hammurabi inscribed on a stela. (Photo copyright Wellcome Library, London, supplied by Wellcome Collection, licensed under CC-BY.)

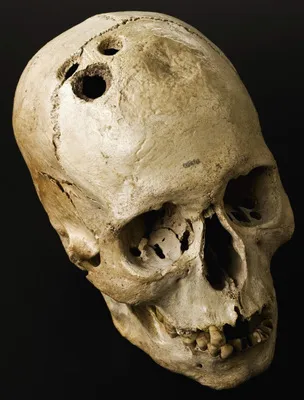

The earliest evidence of surgical procedures is from trephinations performed approximately 12,000 years ago in the Mesolithic era.2 The actual reason for these surgeries is unknown and may have been for ritualistic purposes, but there have been examples found from ancient civilizations throughout the world (Fig. 1.2). From ancient Egypt, the Edwin Smith papyrus, which dates back to approximately 1700 to 1600 BC, is the oldest known medical text and detailed 48 cases of surgical pathologies and their management, including those of injuries of the cranium and spine. These treatments largely involved stabilization to allow healing with time. The Ebers papyrus (circa 1550 BC) was more encouraging of surgical intervention and included descriptions of procedures for the removal of tumors and abscesses.3

Fig. 1.2 A skull that had undergone several trephinations and shows evidence of healing, from 2200 to 2000 BC. (Photo copyright Science Museum, London, supplied by Wellcome Collection, licensed under CC-BY.)

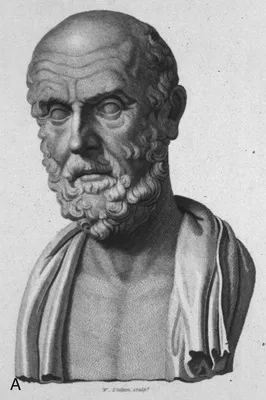

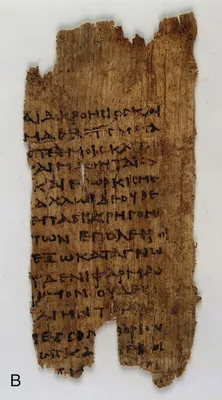

The earliest documentation of trephination comes from Greece. Hippocrates (460–370 BC) is known as the “father of medicine” due to his incredible contribution to the advancement, analysis, and documentation of the practice of medicine (Fig. 1.3A). The Hippocratic Corpus, a large collection of medical works attributed to Hippocrates and others in the Hippocratic School, included the book On Injuries of the Head, which detailed several types of skull fractures and their recommended management.4 In the most famous of the writings within the Corpus, the Hippocratic Oath (Fig. 1.3B), the responsibilities of the physician are outlined, including:

Fig. 1.3 (A) A bust of Hippocrates (from the National Library of Medicine). (B) A fragment of the Hippocratic Oath, from the 3rd century BC (from Wellcome Library, London).

I will follow that system of regimen which, according to my ability and judgment, I consider for the benefit of my patients, and abstain from whatever is deleterious and mischievous.5

Similarly, in Of the Epidemics, the author notes:

The physician must … have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm.5

As in the texts from ancient Egypt, and unlike the code from ancient Mesopotamia, there is no indication of any penalties for complications, but in On the Articulations, Hippocrates does show disdain for those physicians lacking proper “judgment,” to whom he attributes certain complications. He describes the inappropriate treatment of a nasal fracture leading to unsatisfactory healing6:

… those who, without judgment, delight in fine bandagings, do much mischief, most especially in injuries about the nose … those who practice manipulation without judgment are fond of meeting with a case of fractured nose, that they may apply the bandage … the physician glories in his performance … and the physician is satisfied, because he has had an opportunity of showing his skill in applying a complex bandage to the nose. Such a bandaging does everything the very reverse of what is proper … will evidently derive no benefit from bandaging above it, but will rather be injured…5

He also provides advice for the prevention of complications in On Injuries of the Head. The readers are advised to avoid incising the brain to prevent convulsions on the contralateral side and to make the operative wounds clean and dry to prevent gangrene.

Several centuries later, Galen of Pergamon (129–200 AD) followed and expanded on the teachings of Hippocrates. He used his surgical experiences and anatomic dissections of animals to provide detailed descriptions of anatomy, which remained the standard for a millennia, despite some errors.7 He emphasized the importance of the knowledge of anatomy in surgery:

If a man is ignorant of the position of a vital nerve, muscle, artery or important vein, he is more likely to maim his patients or to destroy rather than save life.2

The first recorded medical malpractice case was Stratton vs. Swanlond in 1374 in London. The surgeon had attempted to repair the plaintiff's hand, which had been severely disfigured by trauma. The patient claimed that the surgeon had promised a cure, but her hand remained significantly deformed after the operation, and she filed a lawsuit for breach of contract. Although the case was actually thrown out on a technicality, the judge asserted that a physician would be held liable if harm came to the patient as a result of negligence, but not if he was unable to obtain a cure despite making every effort.8 This decision became a part of English common law, or judge-made law. It countered people's expectation that only a complete cure could be a good outcome and not a complication. The term “malpractice” came about much later; it was coined from the Latin term mala praxis by Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England in 1768. He described malpractice as injuries “by the neglect or unskillful management of his physician … breaks the trust which the party had placed in his physician, and tends to the patient's destruction.”9 The first malpractice case in the United States occurred in 1794, but the overall number of malpractice cases remained low until the mid-1800s.

Infection was a major cause of surgical morbidity and mortality during the long history of surgery before the introduction of antisepsis. Because there was limited understanding of the origin of infections, which were thought to arise by spontaneous generation, hospitals and operating rooms remained decidedly unsterile.10 Many physicians made varied attempts to improve wound healing. Some physicians, such as Paul of Aegina (625–690 AD), used wine-soaked dressings, unknowingly applying antisepsis, but this was not the norm.7 The theory of “laudable pus,” that inducing pus formation encouraged wound healing, has been attributed to Galen as well as Roger of Salerno (fl. 1170) and remained the guideline for wound care until the 19th century.4 Theodoric Borgognoni of Cervia (1205–1298 AD), among others, advocated against the idea of laudable pus. He recommended careful hemostasis, debridement of foreign and necrotic tissue, closure of dead space, and wine-soaked dressings, but his ideas were met with skepticism. Others attempted to explain the transmission of infection but were ignored or rebuked by the medical community. In the 19th century, 80% of patients undergoing surgical procedures developed “hospital gangrene,” and they carried a 50% mortality rate.10 The mortality rate of women giving birth actually increased at this time as physicians took over the job of delivering babies from midwives. Ignaz Semmelweis reported in 1847 that handwashing significantly reduced maternal mortality from puerperal fever, but it still took decades for the practice to become routine.11

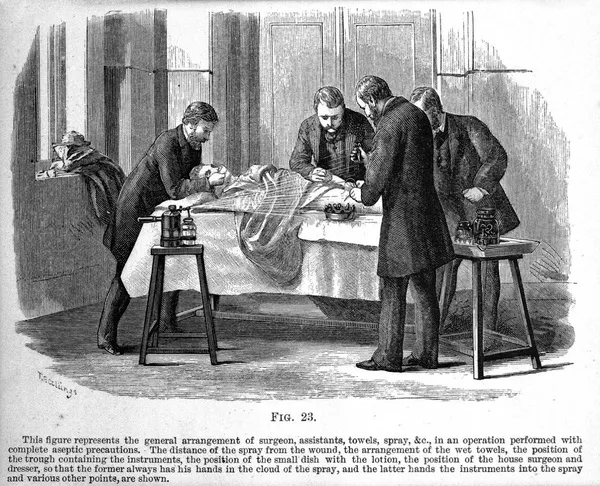

Louis Pasteur's (1822–1895) discovery of the fermentation process supported the germ theory of disease rather than spontaneous generation. Joseph Lister (1827–1912) expanded on these findings to develop the concept of antisepsis, which he delineated in a landmark report in Lancet in 1867. He recommended using carbolic acid for sterilization of instruments, washing of hands, and dressing of wounds (Fig. 1.4).12 Although many physicians were slow to accept Lister's conclusions, the use of antiseptic technique in operating rooms and for wound care reduced the mortality rate after amputations by 30%.13 Even with the incredible reduction in complications that occurred with the introduction of antisepsis, surgeons continued attempting to reduce their rates of infection. Harvey Cushing, often referred to as the father of neurosurgery, noted:

Fig. 1.4 Antiseptic surgery with the use of carbolic acid spray. The drawing is from a book by William Watson Cheyne published in 1882. (Photo copyright Wellcome Library, London, supplied by Wellcome Collection, licensed under CC-BY.)

Even to the painstaking final approximation of the scalp wound, every detail of the operation and the local after-treatment must be followed with the greatest care, if one wishes to avoid that most distressing of all complications, a fungus cerebri, which I am happy to say has occurred to me only twice.14

The emergence of anesthesia in the 19th century was a significant breakthrough in the advancement of surgery. Surgeons had previously been limited by patients' tolerance for pain, requiring them to work as rapidly as possible. The British surgeon Robert Liston was known to be a very good, exceedingly fast surgeon and in fact operated with such speed that he reportedly once amputated his assistant's fingers in addition to his patient's leg (Fig. 1.5). Both the patient and assistant s...