![]()

PART ONE

THE CROWN AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

![]()

THE CROWN, THE CHAIN, AND PEACEBUILDING:

DIPLOMATIC TRADITIONS OF THE COVENANT CHAIN

Rick W. Hill and Nathan Tidridge

We are Indians and don’t wish to be transformed into white men. The English are our Brethren, but we never promised to become what they are.

— Hodinohsó:ni response to request from New Light Reverend David Brainerd to build a church and offer weekly services, 17451

Introduction

When Indigenous nations first encountered Europeans on Turtle Island (North America), they began incorporating them into their own long-established protocols of treaty making. Treaties created the necessary diplomatic space in which very different societies could attempt to communicate and negotiate complex relationships, despite radically different perspectives, including concepts of time and space. Rooted in centuries of ceremony and allegorical interpretation, the Crown was a natural vehicle for settlers to enter into long-term relationships with their Indigenous partners.

Treaties are not static creations, nor can they be captured by a written document. Interestingly, the words often used to explain a treaty can be interchanged with those used to describe the Crown: “honour,” “enduring,” “family,” and “friendship.” These words are necessarily abstract — their elasticity allows them to adjust to the fact that a treaty is meant to be constantly, and consensually, negotiated and interpreted. As well, understanding “treaty,” like “Crown,” requires oral interpretations and attention to story and ceremony, as well as a deep respect for the meanings behind the layers of protocol. Treaty, like the institution of the monarchy, is an organic creation that evolves — or devolves — depending on those who are engaged with it. Both treaty and Crown are meant to be the best reflections of their constituents.

This has not changed in the twenty-first century. The Queen and her representatives remain the “keepers of protocols” for non-Indigenous Canada — at the apex of our national and provincial ceremonies — and are rediscovering their roles as natural conduits into the treaty relationships that thread themselves across the land.

Establishing Treaties: The Two Row Wampum

Hodinohsó:ni (“People Who Make Longhouses”) were one of the first Indigenous nations that made treaties with the Crown of England following the defeat of the Dutch colony of New Netherland in 1664 and the founding of the Province of New York. Together they established a treaty-making protocol, referred to as the Silver Covenant Chain of Friendship, that served to keep peace for nearly 150 years.

Originally a five-nation confederacy, after 1720 the Hodinohsó:ni included six nations.2 The “Crown” meant the King or Queen of the United Kingdom,3 but has come to mean the various governmental agencies and officials making agreements on behalf of the sovereign. This involved, at various stages and to varying degrees, the Privy Council, the Lords of Trade, the Board of Trade and Plantations, Parliament, and the Colonial Office (1768–82), and the Home Office (after 1784). John A. Macdonald’s Indian Land Act (1860) transferred “Indian Affairs” from the purview of the imperial government in London, displacing protocols that had been established through the Silver Covenant Chain, to colonial authorities in the Province of Canada. However, despite the erosion of the treaty relationships following Confederation and its successive legislation (the 1876 Indian Act being a prime example), the representatives of the sovereign as “Keepers of Protocol” are regularly entreated by their Hodinohsó:ni counterparts to return to the ancient protocols that bind them as kin.

Treaties are complex mediums, or relationships, that allow for nations to coexist and interact relatively peacefully. The reasons for making a treaty varied. Generally, a treaty council was required to

- renew peace and friendship between the parties,

- remove grief caused by murder or death,

- heal harm caused by treacherous settlers,

- compensate for lands taken illegally,

- halt rumours of war,

- compensate for harm caused by war,

- end unfair trade practices,

- end religious interference, and

- make up for unfulfilled promises from previous councils.

The Hodinohsó:ni had a well-established treaty-making procedure in place well before the English arrived in the seventeenth century. By making peace, the Hodinohsó:ni metaphorically extended the rafters of their bark-covered longhouses to their treaty partners, treating them like family, to live in peace under one roof (a common law). When the Dutch arrived on Turtle Island (North America), a treaty was needed that would allow radically different cultures to be incorporated into the complex networks and relationships that already existed between the various Indigenous nations. Around 1613 a treaty was entered into by the Dutch and Hodinohsó:ni, codified in what is called the Aterihwihsón:sera Kaswénta, or the Two Row Wampum.

An early seventeenth-century representation in wampum of the Covenant Chain relationship, shown as a rope tying the Indigenous man (right) to the Dutch man (left).

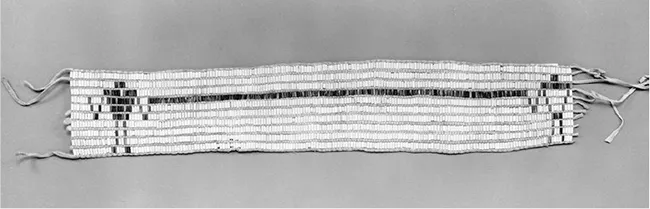

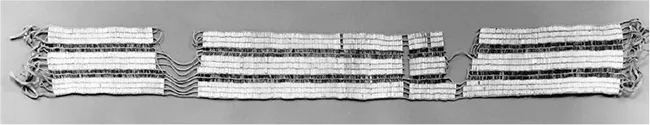

An original Aterihwihsón:sera Kaswénta, or Two Row Wampum.

Wampum diplomacy employed strings or belts woven of wampum, which are small, tubular shell beads. Nothing was considered official unless it was accompanied with wampum. When an agreement or treaty was made, a special wampum usually codified its terms.

The treaty encoded into the Aterihwihsón:sera Kaswénta was archetypal: the Europeans were envisioned steering a large ship that contained their laws, beliefs, and traditions, which came alongside a Hodinohsó:ni canoe containing their laws, beliefs, and traditions. This treaty recognized the sovereignty of each partner, yet agreed on certain principles for sharing the waterways and this land.

Respecting Indigenous nationhood, the people of the ship would not try to steer the canoe, nor force the people of the canoe to abandon their laws, beliefs, and traditions. While history has shown how difficult it has been for the people of the ship to uphold their treaty pledges, the protocols for making amends were firmly in place. As well, there was a commitment that the treaty would last as long as the sun always made it bright on Earth, the waters flowed in a certain direction, and wild grasses grew green at a certain time of year. This would require periodic renewal of the agreements within the treaty so that subsequent generations would understand their obligations.

It was stated in the Two Row Wampum that in the days to come it might happen that dust would accumulate on the agreements, meaning that inattention to each other’s needs might cause trouble. If that happened, it would be possible to wipe the dust from the agreements, making the relationship stronger. The treaty was understood to belong to the faces coming from deep underground (the future generations). Unfortunately, most people have become unaware of the nature and depth of relationships woven into the Two Row Wampum.

The oral descriptions and interpretations that come with wampum diplomacy are laden with analogies and metaphors. Language, and the metaphysical understandings that come with a specific vocabulary, are key to understanding the complex spaces inhabited by treaty, including the necessary protocols and ceremonies that are intrinsic to its very existence. It is within this realm that the Covenant Chain, called Tehontatenentsonterontahkhwa (“The thing by which they link arms” in the Mohawk language), comes into focus.

The Covenant Chain

On August 15, 1694, an Onondaga speaker stated to the representatives of the English Crown: “In the days of old when the Christians came first into this river we made a covenant with them first with the bark of a tree, afterwards it was renewed with a twisted withe, but in the process of time, least that should decay and rott the Covenant was fastened with a chain of iron which ever since has been called the Covenant Chain and the end of it was made fast at Onondaga which is the Center of the five Nations.”4

By this the Onondaga speaker recalled the Two Row Wampum tradition established with the Dutch over eighty years earlier. The Hodinohsó:ni tied their canoe to the ship of the Dutch traders with a rope as a symbol of friendship and equality. The Dutch eventually replaced that rope with a sturdy iron chain, ensuring that the peaceful relationship would last for many generations in the future. However, they did not get to test the long-term strength of that chain, as New Netherland was invaded by the English in August 1664 and Dutch control of the colony was never restored. One of the first tasks of the new English administration was to make peace with the Hodinohsó:ni, who represented both a military and economic opportunity.

Assuming the treaty relationships honoured by the Dutch, English officials quickly embraced wampum diplomacy, while at the same time keeping meticulous written minutes of treaty councils, often reproduced on a large parchment with the terms written in English and signed by the principals who negotiated the treaty in the field.

In this way, three different methods of recording what took place at treaty councils now existed: oral, written, and wampum. While these methods of recording must coexist in order to properly capture a treaty, often times they did not agree, particularly concerning specific details. Indigenous nations relied upon the wampum and their oral memory of what took place, while the British favoured the written record.

The Covenant Chain was symbolic of the agreements that made the Hodinohsó:ni’s relationship and friendship stronger with the Crown. The core idea of the Covenant Chain was that the Hodinohsó:ni, as well as other nations that joined later, and the Crown were linked in peace, having made solemn pledges to keep the principles of respect and friendship in the forefront of relationships that were meant to be enjoyed by all for many generations to come. The Covenant Chain symbolized that the parties would

- acknowledge one another as allies;

- inform each other about issues of concern;

- make amends for any transgressions that may have occurred on either side;

- ensure mutually beneficial trade;

- offer expressions of condolence for the losses suffered by either side;

- seek justice on a variety of political, economic, and social matters;

- renew peaceful relations;

- agree on a course of action that was mutually beneficial; and

- provide military assistance as needed.

A key cultural element in such a process was preparing the minds of the delegates to be able to earnestly speak from the heart, without confusion or deception. In order for a treaty council to have any chance of success, the parties had to first remove any lingering consternation from any trauma suffered by either party. This mind-spirit uplifting protocol began with the formation of the Great Law of Peace. Before the law, violence and death roamed the land. People’s minds and spirits were wounded by what they experienced. Grief and sadness clouded their thinking. The future did not look bright.

In order for peace to prevail, the Great Law of Peace advocated that people use what is called the Good Mind, meaning they treat each other fairly and respectfully. To come to one mind on matters of peace, their minds had to be relieved of any fear, hurt, or prejudice. Wampum and empowering words were used to metaphorically remove the grief and sadness so that people’s minds could once again experience love and hope. Both parties were expected to offer the powerful words shared in a metaphorical space called “the edge of the woods, near the thorny bushes.”5

In looking at the Covenant Chain protocols between the English/British Crown and the Hodinohsó:ni, it is important to realize that before the establishment of the Silver Covenant Chain with England in 1667, the Hodinohsó:ni had already created a treating protocol among Indigenous nations, which had been extended to the Dutch Republic and the French Crown in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The customary practices, or protocols, employed in treaty making included the following:

- Kindling the Council Fire — One party would call for the council and act as host by kindling the council fire over which the words would be shared. Fire was considered a purifier, requiring both sides to speak honestly and earnestly.

- Wiping the Tears — One of the first orders of business was to console the invited party for any losses they may have suffered recently. Once consoled, the visiting party would offer the same ritual of condolence to remove the grief suffered due to the deaths of loved ones.

- Hanging the Kettle — If war was to be declared, this was symbolized by the hanging of a kettle over the fire; if peace was declared, the kettle would be ceremonially removed from the fire.

- Burying the Tomahawk — In the event that battles had taken place, the metaphorical tomahawk, a symbol of war, would be removed from the heads of the victims, cleaned, and buried to symbolize the recovery of normal relations.

- Polishing the Chain of Friendship — A treaty council was called to address a specific list of issues, each codified by a specially designed wampum belt. When peace was first established with the Crown, a symbolic silver chain was created to represent the strength of the alliance. When trouble arose, it was represented by tarnish or rust on the chain that had to be removed (resolved). By agreeing on the peaceful resolution to the matters of concern, the treaty partners symbolically restored the silver chain to its original brightness. By polishing the chain, the parties renewed their commitment to one another.

- Replanting the Tree of Peace — When the Hodinohsó:ni Confederacy was first formed, a tall white pine tree was planted to serve as a safe space where peace could be restored. When making peace, or reaffirming peaceful relations, the speaker would metaphorically replant the Tree of Peace, usually covering up the buried weapons of war.

- Covering the Grave — When harm came to people, their deaths had to be acknowledged and atoned for, usually with presents of wampum or trade goods. This would placate the families of those who were killed, and the parties ceremonially covered their grave, placed a symbolic wampum belt over the grave, and pledged to never speak of the event again.

- Smoking the Pipe of Peace — To conclude the council, after all of the wampum belts were passed back and forth, the delegates of both sides would smoke a pipe to acknowledge their concurrence with what had taken place. The smoke of the pipe carried their words up to the Spirit World, which was believed to be monitoring the treaty council progress.

- Covering the Fire — At the conclusion of the treaty council, the embers of the council fire were covered over, to be rekindled in the future as needed.

Additional protocols, according to “Iroquois Treaty Speeches” by Cayuga Chief Jacob E. Thomas, recorded by Michael Foster, Museum of Civilization, 1976, included the following:

- The inviting council decides on the need for an invitation. It would require council approval. Invitation to be sent to the top authority, who then could decide on whom to send.

- Inviting council sends a runner: Messenger/Runner (“He is Hired”) is delegated and sent with invitation wampum string (“His Burden”) to invite the government to the council. An interpreter might also be assigned and a date set when the runners would leave.

- A message, su...