![]()

1 | How Cyclists Became Invisible (1905–1939)

“Take care to get what you like or you will be forced to like what you get.”

—George Bernard Shaw

THE BICYCLE IN THE BOOM OF 1896–97 was the plaything of the American and European elites, a signifier of status, health, and wealth. In post-boom America, the bicycle regressed, becoming a vehicle solely for juveniles. In 1920s Europe, the mass-produced bicycle evolved into a transport tool for working stiffs. On both sides of the Atlantic, cyclists faded from view. They became invisible in the Netherlands because bicycles were classless and ubiquitous; and they became invisible in Britain and America because bicycles were deemed to be proletarian or for play.

In 1912, a Dutchman resident in America asked a local how wise would it be for him to cycle in Washington, DC. “Such an attempt … would be tantamount to a revolution,” came the tart reply. “In the past few years, so few respectable people have been sighted on a bicycle, that one runs the risk of earning sudden newspaper headlines that few would wish for.”

Bicycling might have been beyond the pale in America, but elsewhere it was still a transport mode with muscle. By the end of the 1920s, the many advantages of cycling, including speed and thrift, brought millions of new cyclists onto the roads of Britain. Some cycle manufacturers promoted bicycles to blue-collar workers as tools of escape. “Is your life spent among whirring machinery, in adding up columns of figures, in attending to the wants of often fractious customers?” asked a 1923 Raleigh catalog:

Don’t you sometimes long to get away from it all? Away from the streets of serried houses … only a few miles away is a different land, where the white road runs between the bluebell-covered banks crowned by hedges from which the pink and white wild rose peeps a shy welcome. Sheltering amongst the trees you see the spire of the village church—beyond it that quaint old thatched cottage where the good wife serves fresh eggs and ham fried “to a turn” on a table of rural spotlessness, for everything is so clean in the country…. Rosy health and a clear brain is what Raleigh gives you….

Hercules, by contrast, pitched its wares at working-class cycle commuters. In 1922, just before the start of a working-class bicycle boom, Hercules was making 700 machines a week. By the mid-1920s, a bicycle could be bought new for what the average laborer earned in two weeks—it was becoming an affordable luxury. By cutting prices even further, and advertising the fact, Hercules sold 300,000 bicycles in 1928. Five years later this had risen to 3 million sales per year. At the end of the 1920s, while manufacturers such as Raleigh continued to make and market bicycles for touring and leisure use, Hercules mostly made utilitarian bicycles. A Hercules bicycle was a workhorse, cheaper than its rivals, but still reliable. In 1939, Hercules made 6 million bicycles, making it one of the largest cycle manufacturers in the world.

With falling prices and rising wages, more and more people became able to afford bicycles. Yet the market growth in Britain, as we’ll see later in the chapter, came at the same time as the government was actively marginalizing cycling.

American cyclists were even more marginalized, even though in a few US cities in the early twentieth century cyclists remained relatively numerous. A traffic count by the Minneapolis city engineer discovered that 1,258 cyclists passed a busy downtown intersection on one day in July 1911, and he counted an average of 669 cyclists per day during a full year of observing the city’s traffic. Horse-drawn wagons dominated, with nearly 3,000 teamster wagons counted, and the number of people on bicycles was only 200 less than the average number of automobiles.

Columbia, one of the oldest and still at this time the leading American manufacturer of bicycles, switched from making high-end recreational cycles to workaday ones. The company’s 1911 catalog suggested: “As a vehicle of daily use, and as a saver of time and … fares for those who would otherwise ride in the street car, there is nothing that gives so much return for a moderate investment as the bicycle.” And these frugal machines were targeted at blue-collar workers:

A great army of men and women daily ride to and from the store, factory, and office; by its means policemen cover long beats and are employed in a variety of service; the letter carrier finds his long route a comparatively easy matter to cover; telephone and telegraph linemen quickly and more easily reach the scene of their work; and thousands of boys on bicycles give to merchants the most economical of any quick delivery service.

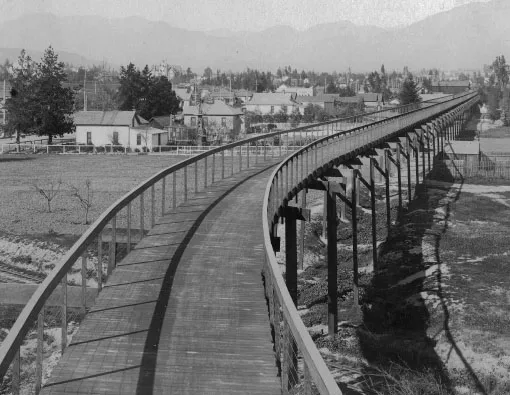

A 1905 US census report on the cycle industry stated that the automobile’s “remarkable growth is not, like that of the bicycle, based on a fad, and so liable to as sudden a decline,” but it remains a stretch to claim, as some historians have done, that it was the automobile that killed the bicycle. The great nineteenth-century bicycle boom fizzled out some eight years before any significant rise in the sale of automobiles. The leisured elites who had flocked to the bicycle at the height of its popularity had rejected it before they sashayed over to motoring. This was exemplified by the fate of the California Cycleway, an ambitious elevated cycling highway built in 1899, but largely abandoned by the following year.

Promoted as an “ingenious scheme” that was to be an uninterrupted “paradise for wheelmen,” the plans for the first elevated highway between the cities of Pasadena and Los Angeles were grandiose, but the grade-separated toll highway that towered over train tracks, road junctions, and slow-poke users of the rutted roads beneath wasn’t completed to length. Only the first mile-and-a-bit was erected, which wasn’t long enough to attract sufficient paying customers. Within just months of opening, the cycleway had become a loss-making stub of a route rather than a profitable cycling road for Pasadena’s many wealthy cyclists. Had it been built to length in 1897, the year after it was first proposed, the cycleway might have turned a profit, and could have become the “splendid nine-mile track” that, in 1901, Pearson’s Magazine (falsely) claimed it was.

Built with pine imported from Oregon, and painted green, the would-be superhighway had a lot going for it. For a start, it had high-society support: it was constructed for a company controlled by Horace Murrell Dobbins, Pasadena’s millionaire mayor, and the investors included a recent former governor of California, as well as Pasadena’s leading bicycle-shop owner. The cycleway was meant to run for nine miles from the upmarket Hotel Green in Pasadena down to the center of Los Angeles. The first short stretch opened to great fanfare on New Year’s Day, 1900, as part of the route of that year’s Tournament of Roses Parade. Three hundred and fifty bicycles, decorated with floral displays, took part in the main parade, and no doubt many of them were ridden down the wooden track by some of the 600 cyclists who took part in the cycleway’s inaugural ride.

Because the truncated cycleway wasn’t terribly long, didn’t go where people wanted to go, and didn’t have enough entry and exit points, it was of little practical value, and hence not used. In October 1900, Dobbins told the Los Angeles Times: “I have concluded that we are a little ahead of time on this cycleway. Wheelmen have not evidenced enough interest in it….”

Despite the fact the California Cycleway was a dud before motoring became popular, newspapers and blogs claim that the cycleway was killed off by the automobile. “The horseless carriage … caused the demise of the bikeway,” wrote the public information officer for the city of Pasadena on her blog in 2009. In 2005, a feature for the Pasadena Star News claimed that “Automobiles spelled doom for the cycleway.” Numerous online mentions of the cycleway have trotted out the same angle. In January 2014, the architecture correspondent for Britain’s Guardian newspaper even claimed that the structure, abandoned in 1900, was “destroyed by the rise of the Model T Ford,” a car not introduced until 1908.

There’s no proof that the advent of the automobile had anything whatsoever to do with the financial collapse of the cycleway. In 1900, motorcars were still fresh on the scene and very few people thought they had a certain future—even fewer thought they had an all-dominant future. By 1905 the scene had shifted, and a writer in that year could truthfully claim that in America at least, “[the] Bicycle [had] had its day.” The pro-motoring author continued: “An Interregnum followed. The ale houses again sank into desuetude and scores of them were not aroused until a year or two ago when the prolonged toot, toot for the automobile horn told them that good times were coming round once more.” In fact, the “interregnum”—a transitional period between two reigns—lasted longer than this automobilist claimed. Elites did not immediately transfer their affections from expensive, status-enhancing bicycles to even more expensive and status-enhancing automobiles: the transitional period lasted from 1898 through to about 1905. This wasn’t because the elites bided their time; rather, it was more of a reflection of availability—there were very few motorcars made in this period, and most of them were made in France.

California Cycleway, Pasadena, 1900. (Pasadena Museum of History)

Bicycling went through a tough period of slackening demand, and it took some years before bicycling became a transport choice for working people. There was a thriving market for secondhand motor cars in America before there was even a sniff of an automobile boom in most European countries, and it was not until 1913 that motorcar sales in America overtook bicycle sales.

Then came darkness. “The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time,” British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey remarked to his friend on the eve of Britain’s entry into the First World War.

The privations of this war led to a reawakening of interest in cycling in Britain (the same happened during the next war, too). “With the present decay of motoring,” wrote a correspondent for the Guardian newspaper, “the push-bicycle has temporarily returned to its own.”

It is now possible for the weary cyclist to push uphill, taking the whole width of the road in his meanderings, without being irritated from the rear by the snappy snort of a car while he is smothered at the front by a plunging motor-bicycle. Three years ago the “push bicycle” had become a mere hack…. With the restoration of our highways and byways to civilisation, the old “tandem” for man and wife has awakened from its sleep; while children, “flappers,” and timid-looking ladies are once more to be seen on their “wheels” as they were about a decade ago, there being little to scare them.

“But,” warned the reporter, “all this is only for the duration of the war, unless road reform includes … special tracks for bicycles like those that run along many roads in Germany and some other Continental countries.”

Special tracks for bicycles had been a feature of roads in the Netherlands since the late 1890s, and as I’ll show in chapter 8, the provision of such cycle-specific infrastructure would continue, in fits and starts, for much of the twentieth century.

IN 1916, in an attempt to revive interest in American cycling, the cycle industry created a promotional platform: Bicycle Week. “The men and women who have persisted in their affection for the two-wheeled friend of mankind will work wholeheartedly for a rejuvenation of its popularity,” wrote the Washington Times. “The bicyclists declare that the wheeling population hasn’t decreased very much…. Bicycle Week is to be observed in all sections of the people who deal in bicycle specialties.”

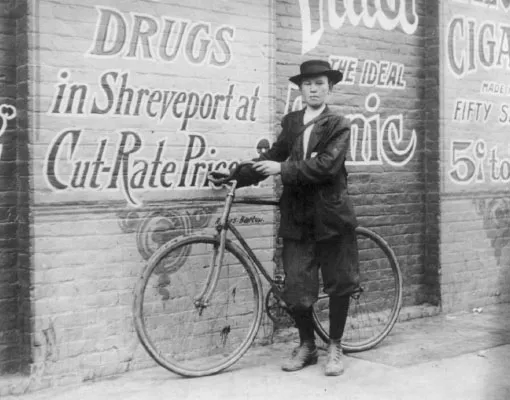

Bicycles were for boys. Howard Williams, thirteen-year-old delivery boy for Shreveport Drug Company. “Goes to the Red Light every day and night,” Shreveport, Louisiana. (Library of Congress)

The promotion wasn’t terribly successful. As one observer put it three years later: “Today bicycling has its place. The young, the strong, those too poor to own motor cars, ride bicycles.”

And for “young” and “strong” read: teenage boys. The US Tariff Commission remarked in 1921 that there “has remained a steady demand for the bicycle as a utility, widely used as a means of cheap transportation by laboring people and by boys.” The Cycle Trades of America advertised to this demographic through the pages of Boys’ Life, suggesting in 1925 that: “The BICYCLE is your best PAL! … The bike is your birthright.” Such ads mostly targeted middle-class boys, but the bicycle was an essential tool for many working-class boys, with the telegram-delivery boy on his often-oversize bicycle being a common sight in American cities from the early 1900s through to the late 1930s. “Western Union Messenger Service is the BOYS’ BUSINESS with a future,” declared an ad in 1926. As historian James Longhurst has suggested, “the telegraph companies might have benefited from emphasizing this idea in order to keep wages down: work done by children certainly didn’t merit a man’s wage.”

The association of bicycling with children—and especially with boys—reinforced the perception in America that bicycles were not for adults. And as the bicycle was now portrayed as a vehicle for mostly children, its presence on roads getting busier and busier with automobiles was increasingly questioned.

Road markings—or the lack thereof—were an effective way to marginalize the bicycle, yet, ironically, they had been introduced by a former cycling club official. Edward N. Hines of Michigan devised the painted highway center line, still one of the world’s most important road-safety features. The first was installed on a rural highway in 1911, on the aptly named “Dead Man’s Curve” along the Marquette-Negaunee road in Michigan. Hines conceived the separation idea when he was a motorist, but his interest in roads had started when he was a cyclist. Back in the 1890s, Hines had been chief counsel of the League of American Wheelmen’s Michigan division, a vice president of the national organization and also president of the Detroit Wheelmen cycling club.

Such lines later marked out lanes for automobiles and parking areas, but few American cities before the 1950s striped their roads to show that cyclists belonged. Washington, DC, was an exception to this. “Another measure on the cyclist’s behalf is marking of special lanes by white lines,” reported Collier’s Weekly in 1939. “You can sight-see in Washington on your bike by sticking to the streets marke...