Treating Trauma in Christian Counseling

Heather Davediuk Gingrich, Fred C. Gingrich, Heather Davediuk Gingrich, Fred C. Gingrich

- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Treating Trauma in Christian Counseling

Heather Davediuk Gingrich, Fred C. Gingrich, Heather Davediuk Gingrich, Fred C. Gingrich

About This Book

Traumatic experiences are distressingly common. And the risks of developing posttraumatic stress disorder are high. But in recent years the field of traumatology has grown strong, giving survivors and their counselors firmer footing than ever before on which to seek healing. This book is a combined effort to introduce counseling approaches, trauma information, and Christian reflections to respond to the intense suffering people face. With extensive experience treating complex trauma, Heather Gingrich and Fred Gingrich have brought together key essays representing the latest psychological research on trauma from a Christian integration perspective. Students, instructors, clinicians, and researchers alike will find here- an overview of the kinds of traumatic experiences- coverage of treatment methods, especially those that incorporate spirituality- material to critically analyze as well as emotionally engage trauma- theoretical bases for trauma treatment and interventions- references for further consideration and empirical researchChristian Association for Psychological Studies (CAPS) Books explore how Christianity relates to mental health and behavioral sciences including psychology, counseling, social work, and marriage and family therapy in order to equip Christian clinicians to support the well-being of their clients.

Frequently asked questions

Information

PART ONE

FOUNDATIONAL PERSPECTIVES ON TRAUMA

1

THE CRUCIAL ROLE OF CHRISTIAN COUNSELING

APPROACHES IN TRAUMA COUNSELING

HEATHER DAVEDIUK GINGRICH

he has not hidden his face from him but has listened to his cry for help.

What Is the Goal of Trauma Treatment?

A Model of Trauma Recovery: The 4-D Model

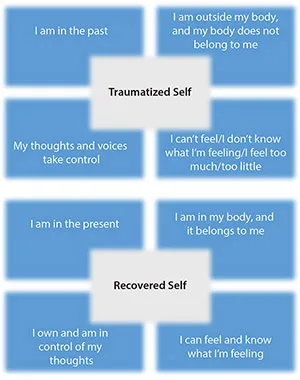

- Time. I am fixated/focused on the past—the trauma—and I am moving toward becoming more focused in the present.

- Body. At times I feel outside my body, that my body does not belong to me, and that things happened to my body, and I am moving toward a clearer sense of being my body and that it belongs to me, that my identity and body are integrated (cf. Levine, 2010, 2015; van der Kolk, 2015).

- Thought. Thoughts and voices or messages are intrusive and take control, and I am moving toward a sense of owning and being in control of my thoughts.

- Emotion. Either I can’t feel anything, I don’t know what I’m feeling, or I feel too much, and I am moving toward being able to feel and knowing what I’m feeling, and it is not overwhelming me.

- To what degree does inclusion of the body as one of the four dimensions make sense? To begin with, the brain and nervous system are crucial parts of the body that recent research findings have shown to be deeply affected by trauma (see chap. 3). Additionally, if we are to be true to a biopsychosocial model of the person (McRay, Yarhouse, & Butman, 2016), we must take seriously the physically disorienting dimension of trauma in terms of somatoform symptoms, and even where the body is in place and time (i.e., with respect to symptoms of depersonalization and intrusive reexperiencing of physical symptoms that can be part of flashbacks). Trauma tends to disintegrate this biopsychospiritual connection, resulting in dissociated aspects of a sense of self and experience (Gingrich, 2013). Also, a strong argument can be made for a biblical anthropology that rests on our being created as an embodied, unified body-soul-spirit (Benner, 1998). Jesus’ resurrection and ascension as an embodied person affirms that the body is essential to our existence. His body was tortured, and even after the resurrection he carried the signs in his body. Of course, the dimensions of thought and emotion are also essential to a biblical anthropology and to our understanding of what trauma destroys and what mental health in God’s image looks like.

- To what degree does the movement from trauma to recovery involve an increased sense of an integrated self and individual identity, as well as identity within or as part of a group (e.g., familial, ethnic, religious)? We briefly looked at the separation of the physical sense of self from the other aspects of self in the discussion of the body in the bullet point above. We also alluded to disintegration of the psychological and spiritual aspects of self. However, the relational dimension of identity that is central in more group-oriented cultures is not addressed by the model. The broader sociopolitical and economic contexts of trauma also are often vastly underacknowledged. This would be particularly evident in disasters, war, and other mass casualty contexts.

- The dimensions of the model, considered in combination, point to some of the complexity of trauma symptoms. But the model does not take into account the differences in severity and life disruption that individuals may experience in response to trauma. Since behavioral symptoms are often most readily observed by others, what does a reduction in symptoms in the other dimensions look like? Change in behavioral symptoms such as compulsive, avoidant, or dissociated behavior, for example, are more easily seen, yet some of the emotional distress may actually be more disturbing for the client.

- Meaning making is a key component of the trauma healing process. This has been emphasized in Park’s research (e.g., 2013; Slattery & Park, 2015). Has the survivor been able to make meaning of the suffering? How will the survivor’s future be affected? What is the role of hope, and how do our current circumstances interact with the future trajectory of God’s involvement with humanity (i.e., our “blessed hope,” Titus 2:13; see also 1 Thess 4:13-18)?

- What is the place of spirituality in the emergence, continuity, and healing of the self? How crucial is it? How does it operate to facilitate healing? Where is God in the midst of the trauma narratives people tell? From our perspective, a model of trauma must consider spirituality as it interacts with all dimensions. For instance, with respect to the dimension of time, we suggest that faith, and particularly a biblical perspective, includes extensive attention to the history of God working in and through difficult situations over time. We believe, therefore, that whichever trauma model we adopt, we should consider spirituality as a key element of what is negatively affected as a result of trauma, along with taking into account the role of spirituality in how trauma negatively affects the whole person and the community and how healing from traumatic experiences can occur.

- Is the ultimate goal simply a recovered self, or is there something more that our spirituality has to offer? Specifically, while the literature (see appendix) refers extensively to coping, resilience, and posttraumatic growth, Christian faith provides hope that the biblical concept of shalom is a real possibility. Referring to biblical passages such as Isaiah 2:2-3 and 11:6-9, Wolterstorff (2013) argues that shalom, often translated as “peace,” is a much richer concept: “But Shalom goes beyond peace, beyond the absence of hostility. Shalom is not just peace but flourishing, flourishing in all dimensions of our existence—in our relation to God, in our relation to our fellow human beings, in our relation to ourselves, in our relation to creation in general” (p. 114). Flourishing is more than basic recovery from trauma—it is the essence of what our Christian faith has to offer (see chap. 2 in this volume for a further discussion of this dimension).

Our Expanded Model of Trauma Recovery: A Multidimensional Model

- Behavior. I don’t always understand why I act the way I do, and I feel as though I don’t have control over my actions, and I am moving toward having a better understanding of and sense of control over my actions.

- Relationships. I don’t have healthy relationships; either I don’t feel close to anyone and so experience emotional distance, or I feel swallowed up by the other person, or I’m terrified of being abandoned, or I feel continually victimized, and I am moving toward feeling connected without fear of abandonment or need to distance.

- Spirituality. I have no sense of purpose in my suffering; if God is even a consideration, either I don’t believe in God or I believe in a God who is judgmental and punitive, and I am moving toward a sense of meaning that has resulted from my trauma; if I have a sense of relationship with God, there is more of a sense of connectedness to God without fear of reprisal.

- Coping, resilience, posttraumatic growth, and flourishing. My life is overwhelmingly negative, and I am moving toward finding healthy ways to cope, discovering strengths and capacities for resilience, actually growing as a result of the trauma, and even flourishing in life.

- Identity. My sense of self is diffuse; I don’t feel as though I am an integrated whole, and I am moving toward having a sense of myself as an integrated whole; I know who I am.