Chapter 1

Howard and Lorrie:

Hearts and Flowers, Plants and Dreamers

There is no country of Canada’s size, importance and wealth with so little to show in the way of botanical gardens.

— HOWARD DUNINGTON-GRUBB

When Howard Dunington-Grubb made that statement in 1959, he had already done more than any other person to rectify the very problem he was addressing. For when he had first arrived in Canada almost half a century earlier, there were few public or private gardens in the country. Canadians didn’t plant flowers or shrubs around their homes. There was nothing like Niagara’s Oakes Garden Theatre. Nor was there a company like Sheridan Nurseries that existed solely for the purpose of growing ornamental plants.

Howard Dunington-Grubb could fairly be called the Father of Landscape Architecture in Canada. He was an artist who worked with a pallet of living things: flowers, shrubs, and trees. His vivid imagination and creativity were expressed on landscapes, in urban gardens, and on a broad avenue in the middle of concrete utilitarianism. Howard sometimes found himself confronted with the pragmatic conservative philosophy that art has no practical use and therefore no fundamental value, as is shown in a conversation that allegedly took place in 1915:

I well remember an interview on a very hot August afternoon during progress of the work on the gardens for the palatial Government House for the Province of Ontario. The Minister of Public Works had some excuse for being brusque. After inspecting stonemasons setting balustrade, cut-stone fountains, pavements, and steps for the terraces, he controlled himself sufficiently to merely ask if these things were necessary. The only possible answer was to admit quite frankly that they were all wholly unnecessary, that we were dealing unfortunately, not in necessities, but in luxuries, and that the only really necessary work involved was a plank walk to the front door so that people could get in and out without stepping in the mud. Garden design in a country devoid of gardens must necessarily be a gradual evolution.

Howard Burlingham Grubb was born in York, England, on April 30, 1881, to Edward and Emma Marie (née Horsnaill) Grubb, both from Letchworth. Edward was a Quaker, and had a distinguished reputation as an editor of Quaker journals. He earned his living as a tutor, and was secretary of the John Howard Society. That organization (still in operation today) was named for its founder, the great pioneer for the cause of prison reform. Edward and Emma named their son Howard in his honour. No doubt it was his parents’ example that inspired in Howard the philanthropic leanings for which he would be known later in life.

Howard grew up amidst the great contrasts of Victorian England. The British Empire was at the height of its glory; a financial and industrial powerhouse. British factories made about 95 percent of the world’s manufactured goods.

The British middle class was growing, but squalor existed side by side with prosperity in England’s booming cities. The families of underpaid factory labourers, as well as hordes of unemployed, were crowded into unsightly, unsanitary slums that were the shame of London, Liverpool, Manchester, and other urban centres. Even the better-off middle-class suburbs were made up of row upon dreary row of low-cost housing, unbroken by green spaces.

Some of the more enlightened city administrators began to realize the need for parks and public gardens; the sort of spaces that had once been considered the exclusive domain of the aristocracy. Middle-class people with a yard and some disposable income wanted to turn their drab city lots into attractive “outdoor parlours” where they could entertain friends with tea and a game of whist on a Sunday afternoon.

This need for greenery and pleasant surroundings in urban areas brought about a demand for landscape architects. The English Garden became a status symbol. It marked the owner as both successful and cultured, even if it wasn’t quite as magnificent as the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. Howard Grubb would bring the basic idea of the English Garden to Canada.

Howard grew up in a comfortable middle-class home. His parents expected him to become a teacher. But Howard didn’t do well at school. According to his own account, he finished last in his class in every course he took. To make matters worse, he couldn’t even make the school cricket or football teams. His family decided to ship him off to America.

This seems to have occurred around 1899. Continuing with Howard’s narrative: after “many years” he “stumbled by accident, without qualifications, into society’s worst-paid profession.” By that, he meant landscape architecture.

Was it really by accident? Was Howard really “without qualifications”? Maybe so. But it seems more likely that Howard had sought and found his calling. In spite of the supposedly dire financial prospects for a young man drawn to “society’s worst-paid profession,” his family evidently accepted and supported his choice.

In 1904, Howard enrolled in Cornell University at Ithaca, New York. Four years later he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Agriculture degree. Not one to wait for opportunity to come knocking, Howard pursued it before he had even finished school. In 1907 he wrote a letter to Thomas Mawson, one of England’s most respected landscape architects. He wanted a job.

Mawson replied, politely advising Howard to stay in the United States. He said prospects there would be better. Three months later, the newly graduated Howard Grubb showed up in his office.

“My name is Grubb,” the young man said.

“Well, what can I do for you?” asked the bemused Mawson.

“I have come to work for you,” Howard said.

“I am sorry to disappoint you,” Mawson replied, “but it is quite impossible. As you will see for yourself, every seat in the office is occupied.”

Not willing to be turned away, Howard said, “Well, sir, I have travelled all the way from America for the purpose of working for you; so you must find me a seat somewhere.”

Probably a little taken aback by the youth’s brashness, Mawson said, “But my dear fellow, I simply cannot do it.”

Howard persisted. “Listen to me, sir. I worked my way back from America on a cattle boat, so that I might have the honour of working for you, and so you simply must take me on.”

When Mawson wrote about the encounter years later, he said, “What could I do in a case like this? It would be wrong not to give such an audacious youth its chance. Within two years Grubb was in charge of my London office.”

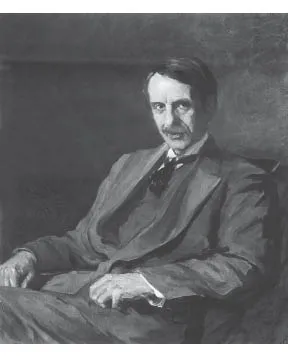

Thomas Mawson personally signed this likeness of himself: “To my old friends Mr. & Mrs. Dunington Grubb [sic].”

Sheridan Nurseries.

Between 1908 and 1910, Howard was in charge of one of Mawson’s most prestigious projects, the Palace of Peace that was being constructed at The Hague, in the Netherlands. The building was to become the home of the International Court of Justice. Howard had his work cut out for him, because even though Mawson had won the contract, he had to work within a smaller budget than he had anticipated.

Lorrie Dunington

Sometime in 1910, Mawson took Howard to a lecture on garden design at the Architectural Association. The lecturer was Lorrie Alfreda Dunington. She had the distinction of being more than a respected garden designer. Lorrie was the first female landscape architect in England.

Born in England in 1877 (making her about four years older than Howard), Lorrie had grown up in India, South Africa, and Australia. At the age of seventeen, she became one of the first female students admitted to the Horticultural College in Swanley, Kent, when she enrolled to study garden design. Upon graduation two years later, she became the head gardener on an estate in Ireland.

Lorrie met the noted gardener H. Selfe-Leonard, who was especially well known for his rock gardens, and formed a partnership with him. They designed gardens all over Britain, and it was quite likely from Leonard that Lorrie acquired the love of herbaceous borders that became her trademark. Leonard had been influenced by the great English garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, and passed her ideas on to Lorrie. It’s possible that through Leonard, Lorrie met Jekyll personally.

Lorrie wanted to go beyond garden design into landscape architecture. At the time there were no conventional courses on landscape architecture in England, so she had to improvise and obtain knowledge piecemeal. She took private lessons from an architect, and she attended a course at a technical college. Lorrie finally opened her own office in London. She practised for several years throughout the British Isles, and won a competition at the Letchworth Garden City. For Lorrie to have been invited to address the Architectural Association, where she was introduced by Mawson and then thanked by the eminent Sir Edwin Lutyens, indicates that her colleagues held her in high regard.

After the lecture, Mawson personally introduced Howard to Lorrie. The attraction must have been swift and mutual, because three months later they became engaged. They each wrote a letter to Mawson, telling him of the engagement and promising to hold him responsible if things didn’t work out. In the spring of 1911, Howard and Lorrie were married.

At that time it was the unquestioned custom for the wife to take the husband’s name. Lorrie would have been expected to formally become Mrs. Howard Grubb. Instead, the newlyweds combined their names and became Mr. and Mrs. Dunington-Grubb. In this regard, Howard and Lorrie were about two generations ahead of the feminist movement. However, it might have been that even though Howard’s friends affectionately called him “Grubby,” Lorrie, who most certainly had a mind of her own, didn’t like the sound of “Mrs. Grubb.” There might also have been a pragmatic reason for the hyphenated name. Lorrie Dunington was a recognized and respected name in the profession. There would have been no sense in losing that connection.

Lorrie had an established business in London, and Howard was well employed with Mawson’s company. Nonetheless, Lorrie convinced Howard that they should pull up stakes and cross the Atlantic to start their new life together. It indeed appears that Lorrie made many of the crucial decisions for both of them. Howard was something of a dreamer and a perfectionist. Lorrie was more dynamic, and was a driving force when it came to business.

Off to the Colonies

Their original plan was to go to New York City. The United States was booming with opportunity. Howard and Lorrie even had a briefcase full of letters of introduction to prominent New Yorkers.

Then they made the fateful decision to try Canada instead. To Britons like the Dunington-Grubbs, Canada was a cultural backwater, where private gardens and landscape architecture were virtually unknown. That could have been the very thing that drew them to it. There would be practically no competition.

Lorrie arranged for them to cross Canada by rail in the summer of 1911. All expenses were paid by the Canadian Pacific Railway. Lorrie was a good writer, and had contracted do a series of articles about their journey for the London Daily Mail. The businessmen who ran the CPR hoped that Lorrie’s articles about the wonderful prospects in Canada would help lure immigrants who would eventually travel on their trains.

The Dunington-Grubbs’ honeymoon was a combination of business and romantic adventure. They crossed what was then called the Great Lone Land at a time when it still had a frontier atmosphere. They visited towns that were the beginnings of great cities. The couple might have decided to put down roots just about anywhere between Winnipeg and Vancouver, but they found “no encouragement” in the West. They finally chose Toronto.

With a population of about three hundred thousand, Toronto was Canada’s second-largest city. In 1911 it was the staid bastion of Protestant values that earned it the nickname Toronto the Good. You couldn’t so much as buy a sinful box of chocolates on a Sunday. Outside of working-class neighbourhoods that housed Italian, Irish, and Eastern European ethnic minorities, the city was essentially British. Union Jacks in their thousands decorated Yonge Street on patriotic holidays.

This 1912 Christmas card designed for Dunington-Grubb & Harries by A.S. Carter was later used for the 1925 Sheridan Nurseries catalogue cover.

Sheridan Nurseries.

Toronto was a city of historic Loyalist roots and strong Anglo-Saxon heritage. A local aristocracy descended from the old land-owning Family Compact, and an upper middle class, whose wealth came from industry and commerce, still saw Mother England as the model for all things a civilized society should be. Toronto seemed the perfect place for Howard and Lorrie. No doubt Thomas Mawson had some influence on their decision. He had visited Canada at the invitation of Governor General Earl Grey, and had made numerous important social connections in Toronto. The Dunington-Grubbs moved into living accommodations at 265 Sherbourne Street, and then went straight to work.

Listing themselves as “Landscape Gardeners,” Howard and Lorrie opened an office at number 10, 6 Temperance Street. They would soon change their self-description to “Landscape Architects.” In the years to come they would move around Toronto to a variety of domestic and business addresses. But in those crucial early months they had to establish themselves so they could build a clientele. For a short period during 1912–13, the Dunington-Grubbs were associated with another landscape architect, William E. Harries.

There was a definite need in Toronto for experts in garden design and landscape architecture at both the private and municipal levels. Howard and Lorrie advertised themselves as: “Consultants on all matters relating to Park and Garden design, Real Estate and Suburban Development, Civic Art and Town Planning.” There is also documented evidence that they were representing Thomas Mawson’s interests in Canada. The following item appeared in the August 1912, issue of The Canadian Municipal Journal:

Mr. H. Dunnington-Grubb [sic], Landscape Architect, Toronto, who is associated with Mr. Thomas Mawson, the English Landscape Architect, will submit plans for the grounds of the University at Calgary, Alberta. Mr. Mawson looked over the ground upon a recent visit some months ago.

It was certainly beneficial to the team of Dunington-Grubb to be associated with so illustrious a name as Mawson. But in all likelihood they’d have prospered even without his endorsement, because no sooner did they hang out their shingle than they were getting work. Wilfrid Dinnick, the developer of the new Lawrence Park Estates, retained them as advisors in 1911 and 1912. Lawrence Park was a suburb of Toronto designed in the style of the...