![]()

1

Toronto’s Passing Scene

Birth of a City

March 6 is a special day in the history of our city, for it was on that date in 1834 that what had been the Town of York was finally given, by royal assent, city status. (And before I get letters saying that the birth date of our community changed with the amalgamation of the city and its surrounding communities on January 1, 1998, I submit that you can only be born once.)

I describe the city as finally achieving city status because there had been several previous attempts to give the community, which had been founded by John Graves Simcoe in 1793, the ability to better administer to its needs without having to seek approval from higher levels of government. Sound familiar?

The document that made this major improvement possible had the official designation “4 William VI, Chapter 23” and was titled “An Act to extend the limits of the Town of York; to erect the said town into a city and to incorporate it under the name of the City of Toronto.”

When this document was given royal assent, it resulted in the new city’s boundaries being defined as: Lake Ontario to the south, Parliament and Bathurst streets on the east and west, respectively, with a line 400 yards north of Lot Street (today’s Queen Street) delineating the northern boundary. Beyond the city proper would be the so-called “Liberties,” an area around the new city into which the community could expand over time. The Liberties stretched as far west and north as today’s Dufferin and Bloor streets, respectively, east out Lot Street to the modern MacLean Avenue, then south to Lake Ontario.

For political purposes the city was divided into five wards with two aldermen and two common councilmen representing each ward. The difference between aldermen and common councilmen had to do with the value of the property owned by their respective voters with the aldermanic position requiring higher monetary qualifications. In addition, the mayor would be elected by the aldermen from among themselves with William Lyon Mackenzie achieving the honour of becoming the city’s first mayor.

And while there was a desire on the part of some of the politicians to introduce the secret ballot at the first civic election, that concept wasn’t adopted until years later. In an attempt to permit the new city to be more self-sufficient the act also permitted the “levying of such moderate taxes as may be found necessary for improvements and other public purposes.” Oops …the door was opened.

One of the most controversial aspects of the act had to do with the community’s name. Though the area had been known for centuries as Toronto, or some variation of that aboriginal word, it wasn’t long after Simcoe arrived that he decided to honour his king back in England (and the man ultimately controlling the purse strings) by renaming the developing community after George III’s second eldest son, Frederick. But rather than calling the place Frederick or some variant of that word (Freddie just wouldn’t work) he selected the young prince’s title, York, for he was the Duke of York. Thus the Town of York was born.

When it was proposed to change that name back to the original Toronto, there was a substantial hue and cry. Many of those opposed thought it was an affront to both the old king and his son even to consider changing the new city’s name. “It must be the City of York!” they argued. Others regarded the proposed new name as being both appropriate (based on the original meaning of Toronto as “place of meeting”) and “sonorous.” Some regarded the new title of Toronto as a distinct improvement over “Nasty Little York” and “Dirty Little York” —two unfortunate nicknames the town had somehow acquired. By a vote of 22 to 10, the Legislative Council agreed to name the new city … Toronto.

Many Happy Returns

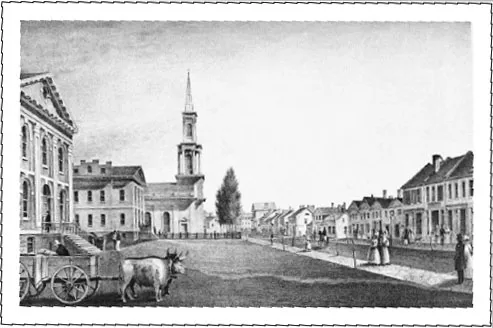

When “Muddy York” became Toronto that day in 1834, it was a city in name, but not much else. With a population of 9,254, it was entirely without any of the ordinary public services and conveniences recognized as essential to an urban community in our modern days. It was bounded on the south by the bay, on the east by Parliament Street, on the west by Peter Street, and had a northerly limit at today’s Queen Street. For the most part, the surrounding area was bush and forest.

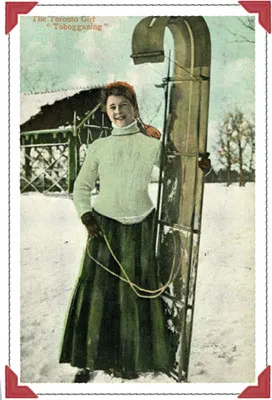

Looking east along King Street toward Church Street in 1835, the year following Toronto’s incorporation. From left to right on the north side of King are the City Jail, the Court House, and St. James’ Church.

The new city had neither water works nor sewage systems; it had no street lighting nor paved roadways. Ditches lined the streets on both sides, and in wet weather these were literally rivers of mud. And, with the exception of the tan-bark footpaths around Jesse Ketchum’s home and tannery on the west side of today’s Yonge Street, south of Richmond, there wasn’t a sidewalk in the entire city.

Now we all know Mayor David Miller and his council have their problems to solve—the main one being fiscal in nature—and interestingly enough, the major problem faced by Toronto’s first city council, led by Mayor William Lyon Mackenzie those many years ago, also revolved around financial matters. In fact, many suggested that the city not be incorporated at all because, and I quote, “the advantages of separate municipal administration would not justify the heavy additional expense that incorporation would bring.” Sound familiar? If you recall, a statement made by Premier Mike Harris’s government a few years ago suggested the opposite would happen with the implementation of his amalgamation proposal. In spite of all the forebodings (those of 1834, not 1997), the incorporation of the new City of Toronto went through.

However, just as today, the first city council faced money problems. The new city desperately needed to undertake a few public works projects. The first one tackled by the fledgling council was the construction of wooden sidewalks. But the materials needed to build these new sidewalks cost money. And the new city had no money. The answer? Place a tax on an individual’s property with the amount to be based on … the property’s assessed value. (Ah, the dreaded “assessed value” practice, something we still grumble over.) This procedure was implemented with a tax rate amounting to “3 pence on the pound.” The implementation of this “staggering” amount resulted in a public meeting being convened at the town market building. Things got out of hand and a riot ensued. So vigorously did the crowds stomp on the floors of the upper balcony that sections suddenly collapsed onto the market stalls below, resulting in the deaths of several of the protesters.

Despite the ill-fated demonstration, the tax rate remained in place. However, insufficient money was raised to construct wooden sidewalks on all of the thoroughfares, so council decided to put them only on one side of the street and only on those streets where pedestrian traffic was significant. And, in order to get as “big a bang” for the few bucks … oops … pounds available, it was agreed that, rather than build wide sidewalks, the 12-inch boards would be placed lengthwise; that way more streets could get sidewalks, though they would be narrower than originally hoped for.

As it turned out, getting the money for the materials was tougher than anyone imagined. That was because when the city officials approached the influential Bank of Upper Canada for a loan of £1,000 to start on the sidewalk project (to be paid back when the property tax money began arriving) they ran up against Dr. Christopher Widmer (for whom Widmer Street is named), the bank’s petulant president. In the municipal election held a few weeks after the city was established, Widmer had been defeated in the race for a seat in St. David’s Ward by none other than that “trivial” Mackenzie, the bane of the Family Compact’s existence. Angry at his defeat, Widmer emphatically refused to loan the new city the £1,000 it had requested. As a result, the mayor and several members of his council had to go to the smaller Farmer’s Bank where, after putting up personal collateral, a loan of £1,000 was approved and the sidewalks were built.

And Mayor Miller thinks he’s got troubles.

Our Mother of Invention

Today, when we think of the Canadian National Exhibition, we usually think of the midway, horse and dog shows, and musical concerts at the Bandshell. But there was a time, long before shopping centres and shopping channels came into being, when what was initially called the Toronto Industrial Exhibition was the place to witness the latest in agricultural innovations as well as to see and try the newest of man’s inventions.

Of particular interest to many fairgoers was the myriad of items that worked thanks to some new and mysterious thing called electricity. No one really knew what electricity was or how it made things work, but they could certainly get their fill of this “wonder of the age” at the Exhibition.

Interestingly, the CNE was an early proponent of electricity and has the distinction of being the first outdoor fair in the world to be illuminated at night. All those lights allowed people to stay on the grounds long after darkness had fallen. And then there was radio. In fact, the very first “plug-it-in-the-wall-outlet-and-sit-back-and-relax” variety was shown at the Exhibition in the late 1920s. These AC-powered devices, invented by young Torontonian Ted Rogers, did away with the cumbersome and expensive batteries that had been necessary to operate the now “old-fashioned” radios.

Each year the newest in refrigerators, washers, dryers, stoves, and high-fidelity and stereo sets were highlighted in the CNE’s Electrical and Engineering Building, a massive structure that stood where the Direct Energy Building is today. By the way, for our younger readers, those high-fidelity and stereophonic record players your parents and grandparents saw at the Ex were the forerunners of today’s MP3 players. And while on the subject of records, the oldest recorded sound in existence anywhere is the voice of Lord Stanley, Canada’s sixth governor general (and yes, he was the man who donated the Stanley Cup that the Toronto Maple Leafs will one day win again). It was during Lord Stanley’s visit to the 1888 edition of the fair that he recorded a message of welcome to visitors to the Exhibition from the United States. The instrument on which he made this recording was a brand-new invention from the factory of Thomas Edison, a machine that “the Wizard of Menlo Park” called the Perfected Phonograph.

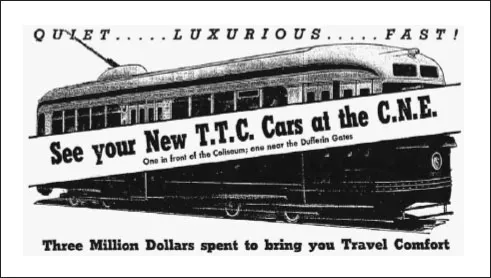

Another invention witnessed for the first time anywhere in the world at the Exhibition was the trolley pole, a device still in use on all TTC streetcars by which electricity is collected from overhead wires. The original trolley pole was used on the Industrial Exhibition’s experimental railway, an attraction that carried hundreds of amazed passengers on a short piece of track at the north side of the fairgrounds. They were amazed when the little cars began to move and there wasn’t a horse in sight. Of course, the city’s regular system used slow, plodding, horse-drawn streetcars to get people around town.

Over the next few years the Ex’s experimental street railway continued...