![]()

1

RICHARD SUGDEN WILLIAMS: THE EARLY YEARS (1834-1856)

Immigration and settlement of the Williams family in Ontario; R.S. Williams’ school years; the path to an unexpected profession.

The early nineteenth century saw the beginning of musical-instrument manufacture in Canada. A barrel-operated organ made by Richard Coates in 1820 can still be seen in the Church of the Children of Peace at Sharon, Ontario. Pierre Olivier Lyonais was active as early as 1825 as Canada’s first known professional violin maker. Piano building started in the province of Quebec, with makers such as Frederick Hund (c. 1816), G.W. Mead (c. 1827), and J.M. Thomas (c. 1832).1 Although Richard Sugden Williams was not among these earliest instrument makers, he nonetheless was one of the important followers who built on the foundation laid by the first Canadian craftsmen. He helped establish the industry and raise public interest in music. Indeed, an important part of understanding the development of this industry in Canada is appreciating Williams’ role in it.

On April 12, 1834, a son was born to Richard and Jane Williams of Great George Street in London, England. He was christened Richard Sugden Williams at St. Margaret’s Church beside Westminster Abbey on August 3, 1834, and was raised in London for four years. The boy’s life was then suddenly changed by his parent’s decision to emigrate to Canada. The reasons for this decision have never been recorded; it is impossible to know whether the Williamses left to escape the stormy events of troubled Britain in the 1830s, or whether they were motivated by personal and family considerations.

The long ocean voyage to Halifax was followed by what was at that time an equally arduous trip by bateau, steamer, stage coach, and again by steamer to Toronto. It is possible that news of the Rebellion in Toronto reached the Williamses as they neared the end of their journey. For this or other reasons, the family decided against staying in the capital of the province and went instead to Hamilton. Richard Williams is described in the local records of that city as a retired gentleman.2 A second son, William Hodgson Williams, was born in Hamilton in 1839. In 1841, when both children were still quite young, the family moved to Toronto. These two Canadian cities, Hamilton and Toronto, were to provide R.S. Williams with the beginnings of a career in musical instruments.

Thanks to his parents, Richard Sugden Williams belonged to the one-third of children who benefited from the education system. (The rest did not attend school at all.) His education started in a Toronto common school organized according to the First General Common School Act of Canada of 1840. The majority of his schoolmates were boys and girls from ordinary families of workers, farmers, and small tradespeople. “The boy received a common school education, chiefly under the tuition of the late Mr. Darby, a master of the olden time, not easily forgotten by the school boys of that day.”3 The pioneer schools provided a strict and formal education: R.S. Williams would have been encouraged to be obedient and respectful to his elders and to be uncritical in the acceptance of concepts and notions approved by the authorities. Independence of thought was discouraged.4 One wonders what factors in his personal and family life enabled Williams to overcome these restrictive elements in his early training and to put his education to good use in his rise to business and social success.

Having in mind R.S. Williams’ later career, one looks to his boyhood for influences on his personal attitude towards the world of music. There is good reason to believe that the stream of such influence did not flow from the years of his school education. In the elementary schools of that time musical instrument was absent, and even singing was dependent on the good nature, enthusiasm, and ability of the teacher.

In searching for the origin of the Williamses’ tradition as musical-instrument makers, one reporter who interviewed R.S. Williams suggested that, as his forefathers for several generations had been builders, the famous Canadian piano manufacturer inherited the building instinct naturally.5 The persuasiveness of this idea fades, however, when no documentary evidence is found. R.S. Williams’ father was a cook; none of the grandchildren of the founder of the family music business recalls any predecessor following a career in musical-instrument manufacturing.

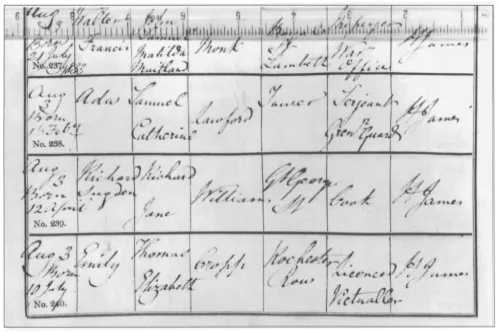

Record of R.S. Williams’ baptism. (Courtesy Dean and Chaper of Westminster.)

The assumption that R.S. Williams inherited his interest in musical instruments might be based on a misinterpretation of a story about a family heirloom, a violoncello that was made by Jane Williams’ grandfather and which the Williamses brought to Canada. The shape and workmanship of this instrument, included in the R.S. Williams Collection now in the Royal Ontario Museum, reveal a rather naìve imitation. It might be supposed, however, that the old cello, as the most peculiar piece of the family furnishings, might have drawn the boy’s attention. R.S. Williams’ ultimate career suggests that his early curiosity might have been aroused not by the playing, not by the sound itself, but by the cause of the sound, by the functioning of the instrument.

Strong hints of the boy’s remarkable skill in the use of various tools appear in his biography, which also mentions his success in repairing various small musical instruments.6 Perhaps young Williams was also influenced in his choice of career by the location near his school (and not far from his home) of a musical-instrument manufacturer’s store and workshop, at 153 Elizabeth Street.7 The manufacturer’s name was William Townsend; Williams was apprenticed to him in 1846 to learn the piano, organ, and melodeon industries.8 About Townsend himself, it is known that he came from New Hampshire, “the birthplace of the melodeon.”9 Jeremiah Carhart and others from Concord, New Hampshire, had introduced to Toronto the modern instrument with its suction bellows.10 The article describes “Townsend & Co.” as one of the leading melodeon manufacturing firms of Toronto in the 1840s. It seems, however, that all of this information originates with R.S. Williams. Except for the appearance of Townsend’s name and occupation in city directories – musical-instrument manufacturer (Toronto), and organ builder (Hamilton) – little documentary evidence can be found about him and his business. Alas, not one of Townsend’s instruments even appears in Michel’s Organ Atlas, the popular and most comprehensive (for North America) source of such documentation.

Whatever the capabilities of William Townsend, his influence on the young R.S. Williams appears to have been remarkable, and the boy’s parents made a good decision in apprenticing their son to him. The Statute of Artificers had been repealed in 1814 and after that time apprenticeship was on a voluntary basis; nevertheless, the custom of paying the master a sum of money as a consideration for accepting an apprentice remained.11 Perhaps Richard Sugden’s father paid Townsend the usual £10; perhaps the master did not take any money but accepted the boy as a favour to the parents and as a way of gaining a hand for his workshop and business for the traditional seven years.

At the time of Richard Sugden’s apprenticeship, every part of the instrument had to be manufactured by hand. This gave the young craftsman excellent training and thorough proficiency in all details of the business. But the way to knowledge and skill was not simple. For example, a number of different operations were required to build a melodeon; the making of the case, bellows, and reed frame were the most essential.12

As would any other apprentice in the business, R.S. Williams must have been trained to make straight, clear pieces out of warped, checked, or knotty timber. Walnut and rosewood logs for resawing veneer were stored in the workshop along with sheets already prepared for use. The big vise saw would eventually have become familiar to the boy, who had to know how to resaw the logs held vertically in the vise. He would also have become familiar with the huge and heavy workbenches with holes on the top and in the legs for the holdfasts and the bench dog. Gradually he would have learned to use the jointing plane, the jack plane, the large smooth plane, and the small rabbet plane, the tools of the true cabinetmaker.

There was also the mechanical work: helping to cut pieces from sheets of brass for hinges; assisting in cutting frames for the reeds (or “brass” as they were generally called), narrow strips or tongues of thin, hard, yet elastic metal. As soon as the metal frames were ready, furnished with a rectangular aperture, these tongues were fastened above them by one end. This was entirely the masters’ business, as was the voicing and regulating of the reeds.

A successful apprentice in musical-instrument building needed a number of skills and talents. He would have had to deal with a wide variety of problems, from repairing a cracked violin, to replacing the broken hammer of a pianoforte, to restoring the watchkey screw-mechanism of a one-hundred-year-old English guitar. Townsend must also have initiated Williams into the secrets of free-reed voicing and of the regulating and tuning of melodeons. This job was fairly complex, but the tools required were few: small half-round and flat files with a safe edge, a half-round steel burnisher, a pair of small round-nosed pliers, a watchmaker’s hammer, a small scraper, a reed hook for taking the reeds from the panel, an ebony block, a block of polished steel for use as an anvil, and a steel slip for tuning.

There were other sorts of things that Townsend would have taught his talented apprentice. The young Williams must gradually have become familiar with the organization of the business. He would have learned the importance of gaining the trust of his co-workers and his customers alike.

In 1853 the seven-year apprenticeship ended; Richard Sugden Williams was a highly skilled journeyman. In the same year he moved to Hamilton with his master and their musical-instrument business.13 The years in Hamilton marked a turning point in Williams’ career and in his personal life. At nineteen years of age, he was introduced to a girl who had come to Hamilton with her parents from the United States just a year before Richard Sugden followed Townsend there. Her name was Sarah DeMain Norris; the daughter of Robert and Mary DeMain Norris. February 1854 saw the wedding of Richard Sugden Williams and Sarah. Their first child, Robert, was born November 29, 1854.

At this time the entire musical-instrument industry was shaken by a shrinking market, and a business such as Townsend’s was vulnerable to such change. In 1855, just two years after the move to Hamilton, Townsend’s company failed. The London Free Press, which got the story from R.S. Williams some forty years later, put it this way:”

All this happened when R.S. Williams had just entered his twenties, and only a rare dedication to his profession could have given him the enthusiasm and strength for the task of heading the whole business and managing it. He did manage it so well, in fact, that it would become the basis of his later success.

The entire year of 1855 kept Williams so busy with preparations for moving back to Toronto, a city of continuing rapid progress and of many positive signs that the roots of his business would be planted in fertile soil. Williams’ frequent trips to Toronto must have made him aware that competition with businesses already flourishing there would be keen; however, visits to the music and musical-instrument dealers in Toronto would also have provided him with a number of possible business contacts. As it happened, all of these businesses were located on King Street: Joseph Harkness; Haycraft, Small & Addison; A. & S. Nordheimer; and John Thomas & Son.15 The Nordheimer brothers, Abraham and Samuel, had moved their business from Kingston to Toronto while Williams was working with Townsend in Hamilton. Theirs was the most prosperous firm of all, importing sheet music and pianos.

R.S. Williams must have been glad that the Nordheimers were not especially interested in melodeons. He originally planned to base his business on the manufacture of melodeons partly because of their popularity, partly because of his experience and skill in building them. However, early in 1855 came news that musical instruments, especially those imported for the use of military bands, were to be admitted into Canada free of duty. This may have influenced Williams to consider expanding his plans to include trading in imported instruments of this type. He must have become convinced that Toronto, then twice as big as Hamilton, would offer him a good business opportunity.

The move to Toronto was made. In the Directory of 1856, both Richard and R.S. Williams are listed, the former as “cook and confectioner,” and the son as “melodeon manufacturer” and under “Music and Music Instrument Dealers” in the “Professional and trades directory” section.16 Although Hamilton remained important as a turning point in R.S. Williams’ life and in the life of his family, Toronto was the city in which the family business was to flourish for decades to come.

![]()

2

STARTING OUT UNDER THE BIG FIDDLE (1856-1864)

Toronto’s musical climate; establishment of the new firm; early...