eBook - ePub

Under the Guise of Spring

Eugene Lane-Spollen

This is a test

Share book

- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Under the Guise of Spring

Eugene Lane-Spollen

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A mesage to a Medici, unseen for 500 years has been found. It reveals the true purpose of Botticelli's Primavera, while opening a window on the cryptic world of the Renaissance Pagan Revival.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Under the Guise of Spring an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Under the Guise of Spring by Eugene Lane-Spollen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Fiction historique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Fiction historiquePART I

Overview

1

Introduction

LA PRIMAVERA, more than five hundred years old and one of the world’s most intriguing paintings, has remained an enigma despite one hundred and fifty years of research and interpretation. Painted for the powerful but embattled Medici, the de facto rulers of Quattrocento Florence, its diverse moods have fascinated and perplexed the millions of people who have stood before it over the years in the Botticelli Room of Florence’s Uffizi Gallery and wondered at its meaning.

Understanding La Primavera across a void spanning five centuries, to a culture dominated by a pervasive religiosity and with dramatically different priorities from today’s Western society, is a challenge. La Primavera must be understood in the context of the lives, times, customs and social currents surrounding the powerful Medici family in the tempestuous politics of late fifteenth-century Florence.

It was a period which we now call the Renaissance, or re-birth, when the re-discovery of Man’s worth and dignity, as portrayed in recently discovered classical manuscripts and works of art, ignited the imagination, causing an explosion in creativity unequalled before or since.

La Primavera was created in that extraordinary period when a newly energised and prosperous Florence, largely recovered from the Black Death, had become a cultural centre of the world, having absorbed influences from Northern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean over many centuries, and its own pre-Christian history. It was an age that helped shape today’s individualism and self-reliance and one which was gradually prising loose the grip of an unquestioning religious conformity. Under the influence of classical antiquity it restored the dignity of the individual and honoured merit for its own sake. It glorified knowledge and self-assertion and its art evoked a deeply human spirit. The idealised ‘Renaissance man’ was like a god, without limits, powerful, self-confident, compassionate, just and utterly capable.

A new merchant class had evolved over centuries of political struggle to eclipse the old nobility. Trade flourished and the resulting wealth was frequently lavished on works of art and architecture that exalted the patron. For bankers, moneylenders and merchant adventurers, art patronage, most of it religious, was perceived as alleviating the final cost of life’s misdemeanours.

The story of this painting has its beginnings in the Pazzi Conspiracy of 1478 against the incumbent Medici. Had this conspiracy, approved by Pope Sixtus IV, not resulted in the death of Giuliano de’Medici, La Primavera may never have been painted. The concept of the painting had to be appropriate to the man who took his place. Giuliano was brutally murdered during high mass in Florence cathedral, but his brother Lorenzo, called ‘The Magnificent’1 and the head of the family, survived. With Giuliano dead and the Medici under severe political and financial pressure, The Magnificent pursued a financially beneficial and politically astute marriage alliance with the Appiani family, Lords of Piombino, whose ports were coveted by competing powers including Naples and Milan.

The young groom and ward of The Magnificent who stepped in to replace the murdered Giuliano in the family’s wider interests, was from a branch of the family uninvolved in the government of the city state. He was Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’Medici, or Lorenzo Minore, whose father had died a few years earlier when he was thirteen. He became the owner of La Primavera which circumstantial evidence suggests was a marriage present. Just fifteen years of age at the time of Giuliano’s death, and unburdened by the maintenance of a costly political architecture, he was one of the known world’s wealthiest young men.

The search for a sound understanding of La Primavera – one that accounts for all we see – has given rise to an immense body of interpretation. During the early Renaissance a language of sophisticated allegory emerged; ideas were expressed by a code of symbolic pictures and little was as it seemed. The smallest detail had a role and the whole spoke volumes to those with insider knowledge and a privileged education.

La Primavera opens a window onto society, religion, philosophy and mankind in general during one of the most influential periods in European intellectual history. In recounting the search for the meaning of the painting, this volume will shed light on a new kind of humanity inspired by the classical age.

The Medici, a family of simple background who had risen to great wealth and power, emerged in the 1400s at the forefront of a small number of competing oligarchs. They pursued a broadly based programme of cultural renewal of extraordinary scope and ambition, seeking to make the city state the cultural heir to Athens and Rome. Their contribution to the recovery of long-lost classical manuscripts helped illuminate Italy’s pre-Christian origins.2

An understanding of the classical age had to a large extent been lost following the fall of Rome to barbarian hordes. Surviving manuscripts lay in obscurity in convents, monasteries and remote outposts across what were once the lands of the Roman Empire.3 The Medici financial resources and network of agents greatly aided an extraordinary effort for their recovery. The works of some of the greatest minds of antiquity were progressively unearthed, brought to Florence and eagerly translated. They shed light on what was perceived as a sophisticated and liberal age in contrast to their own, a lost glory which brought current disillusionment into ever sharper focus. They were captivated by the idea that such a society was their own estranged patrimony, the vestiges of which lay beneath their feet. Sandro Botticelli, the unlettered but sophisticated allegorist whose mystical instincts resonated with the Medici circle, would capture the spirit of these times.

La Primavera and the Classical World

La Primavera features classical gods from a pagan past.4 Images of gods and goddesses such as Venus were purged during the struggle for recognition by the fledgling Christian Church. At the beginning of the fifteenth century many ancient works of art, mostly sculptures and manuscripts which are famous today, had yet to be unearthed. It was not until the final thirty years of the fifteenth century, from around the time Botticelli opened his workshop, that classical sculptures began to emerge in substantial numbers and were appreciated for their workmanship and beauty.5 How and why the discovery of the classical during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, in its myriad expressions, pervaded the spirit of the age in which La Primavera was painted, and fired the collective imagination is important to this story.

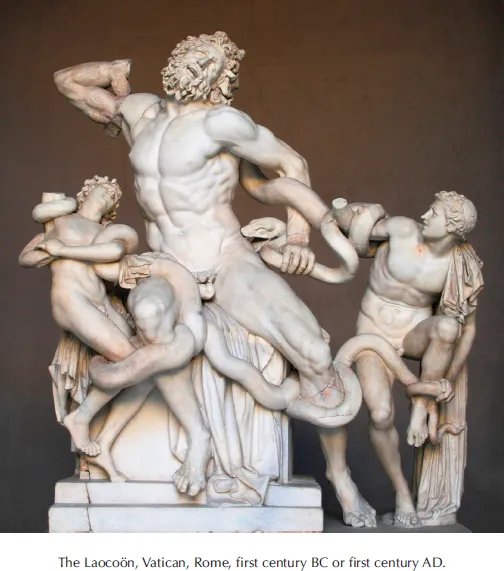

Classical marbles unearthed in the ruins of Rome such as the Laocoön, found in 1506 in Nero’s Domus Aurea pleasure complex, stunned the erudite with their refinement and naturalistic representation of the human body. The profound humanity and emotion of such works and their exalted portrayal of man, contrasted dramatically with the humbler Christian self-view and greatly engaged Florentine society. These discoveries informed the ideas and art of the early Renaissance, such as Botticelli’s, and also the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael at its apogee during the bella maniera of the high Renaissance in succeeding decades.

The New Learning

The rediscovery of the ancient world fanned the desire of many Florentines to deepen their knowledge of dimensions beyond the confines of artistic expression. Exposure to classical culture brought an understanding of an age when humane values were to the fore and man, not God alone, was at the centre. Eventually called ‘Humanism’, its thirst for insights into the culture and values of the classical age of Greece and Rome planted the seed which would have lasting consequences for Western civilisation in the centuries ahead.

The Humanism of the 1400s was accompanied by a surge of dynamic inquiry into the philosophers, poets, historians and orators of that lost age. The ideas which emerged, first in Latin and later in Greek, became fashionable among the cognoscenti, gathering adherents and spreading abroad a new manner of thinking about the human being, his purpose and role.6 The Humanists saw this ‘new learning’ as leading man out of a narrow age of decay and ignorance into one bathed in classical enlightenment. The emphasis was on the self and individual merit and achievement, not guilt or sinfulness; on beauty and sensuousness, not austerity. They honoured man and recognised in him something god-like, all of which found expression in painting, sculpture, music and poetry. It brought forth a growing self-belief among many who were no longer satisfied to huddle with the crowd in the shadow of institutions, or remain paralysed by the tyranny of social station. Pinturicchio was to place the sciences, once the vassals of theology, at the feet of a human being, Rodrigo Borgia (1431-1503). On his coronation as Pope, Alexander VI in 1492 accepted inscriptions which celebrated him as ‘greater than Caesar’, stating that ‘the other was only a man; this is a god!’7 Galileo would later assert that God’s knowledge of mathematics differed from our own only in quantity, not in kind.

The convergence of many aspects of the new learning in the pagan revival were described by the Venetian friar Francesco Colonna (1433-1527) in an epic work which elegantly captured the mood of Renaissance intellectuals torn between nostalgia for lost greatness and religious fervour in an age disillusioned with institutionalised religion. The reader was introduced to concepts which emphasised human beauty and creativity. Perhaps more important was the permission these ideas granted to celebrate life and living, and to ‘love the stuff and surfaces of this world’.8

In similar vein, a Franciscan monk, whose words ‘shake with the laughter of the human soul’, wrote:

there ought to be no clock summoning the individual to their duties, no monks or nuns, noth...