![]()

1

Steamboats on the Upper Lakes

FROM FIFTEEN KILOMETRES (about nine miles) offshore the town of Collingwood, Ontario, squats on the horizon, barely distinguishable from the flat lands of Wasaga Beach bearing southeast and the rising hills of the Blue Mountains to the southwest. On a clear day the white grain elevator is the landmark to bear on while keeping an eye out for the Nottawasaga Light just off the starboard bow. It is only from a distance of about one kilometre out that the town’s old name, “Hens-and-Chickens,” makes any sense, the harbour area having been named for the one large island with its nearby clutch of four small islands.

Collingwood’s old name hints at the harbour’s dangerous underwater topography. When the level of Georgian Bay is low, as it is every so often, there are scores of small sharp limestone shoals that become tiny grey islands. One of the islands that used to be a shoal was One Tree Island.1 Today this island has been joined to the mainland and is called “Brown’s subdivision.”2 The bass fishing used to be good there, good not just because it was a shoal, but because the scattered remains of the sidewheel steamer Frances Smith provided underwater refuge for fish. Now the steamer’s remains are buried under a housing development. Any remaining parts of the vessel have been crushed under the blade of a bulldozer, paved over with asphalt or turned into somebody’s lawn.

Most local fishermen don’t know anything about the Frances Smith. A few of the old-timers from around Nottawasaga Bay, an extension of the much larger Georgian Bay, recall that the Baltic rested on the bottom near the island. Fewer still know that the Baltic and the Frances Smith are one and the same.

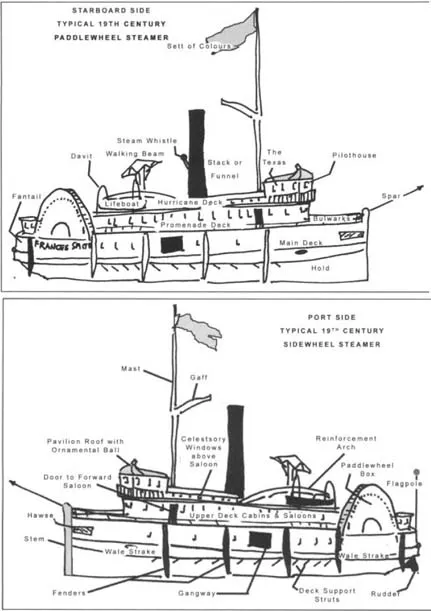

Top: Sketch of the port side of a typical nineteenth-century sidewheel passenger steamer. Bottom: Sketch of the starboard side of a typical sidewheel steamer showing several parts of the vessel.

The Frances Smith was the first steam passenger ship to be built in Owen Sound on Georgian Bay. Back then, in 1867, she was called “a palace steamer,” “the pride of her ports” and “a first-class upper-cabin steamer.” In her glory days she was advertised as “a splendid and commodious steamer.”

In her time the Frances Smith was the queen of Upper Great Lakes shipping. She was a gleaming, white, oak-framed, wooden sidewheel steamer, whose characteristic whistle was a familiar sound for thirty years from Collingwood to Thunder Bay. She was fast, sleek and extremely stable in heavy seas. Her stability came from the huge paddles on each side acting like sponsons, insuring that the 27.7-foot-wide vessel did not roll as severely as a screw-propeller ship would in rough weather. Inside each of the 30-foot paddle boxes mounted on the sides of the ship was a great wheel fitted with paddles over six feet wide, churning in tandem. Her small pilothouse, perched 24 feet above the waterline, was set immediately forward of a 50-foot mast that could be fitted with a gaff-rigged sail. Abaft the mast, a raised curved platform on the hurricane deck was fitted underneath the curve with transom windows, which allowed light into the saloons below.3 The most prominent features on the upper hurricane deck were the tall twin smokestacks (reduced to one in 1869) and the iron walking beam connected to the engine deep in the ship’s hold. When under full steam, black wood smoke and sparks spewed from the stacks while the walking beam rocked back and forth like a giant metronome, driving the paddlewheels by means of a massive crank.

At the bow of the ship was a hinged spar that could be raised or lowered to an almost horizontal position for steering guidance. At the broad round curved stern on the main deck was an open fantail from which a perpendicular flagpole was mounted. Above the fantail on the promenade deck were the upper cabin sleeping quarters, each marked with twin arched windows.4 Each window was fitted with a sliding shutter built into the outside wall of the cabin. The shutter could be raised for privacy, for security against violent weather and for darkening the cabin.

The 181-foot Frances Smith was launched in 1867, just two months before the date of Canadian Confederation. From bow to stern, she was state-of-the-art in ship design. By the time her remains were towed to their final resting place at One Tree Island, she had become a legend on the Great Lakes. She had a record of service unmatched by any other steamer around Georgian Bay. She had endured her share of troubles along the rocky coasts of the upper lakes, both from the natural elements and from events aboard ship, and, like many 19th century vessels without 21st century communication technologies, she had experienced several accidents and near disasters. Like the Victorian society she served, the Frances Smith displayed both pomp and circumstance when the occasion demanded. This then is a the story of a grand lady of the steamship era and the tough reality of shipping on the Upper Great Lakes in the 19th century.

* * *

The story of the Frances Smith begins with events far from Georgian Bay where she was built and where she sailed throughout her entire life. Her creation was the dream of one man, Captain William H. Smith, who was responding to emerging economic and social forces in Europe and North America in the mid-1800s.

By the time Lord Cardigan and his six hundred men rode into the “Valley of Death” during the Crimean War in October 1854,5 life in Canada West (Ontario) had changed from just two decades earlier. In the 1830s, pioneers were still hacking primitive roads into the wilderness north of Lake Ontario. By the 1840s the first paddle steamboats6 had chugged and splashed their way around the upper Great Lakes, and there were now several steamers making routine trips from Penetanguishene to Lake Huron, Manitoulin Island, the North Channel and Lake Michigan ports. Schooners on similar routes would continue to outnumber steamers for another four decades, yet steamers were making serious inroads into the way transportation systems on the upper lakes operated. Their increased speed, capacity and reliability more than offset their high capital cost and relatively high operating expenses.

One consequence of the Crimean War was that prices for grain soared in Britain. In Canada the price of grain reflected the demand/supply economics across the ocean. The rising price in turn redoubled the efforts of the new settlers on the south shore of Georgian Bay to clear-cut the forests and plant crops for export. At the same time, Collingwood was just about to complete its railway link to Toronto. When the Ontario, Simcoe and Huron Union Railway (OS&HUR) (popularly known as the Northern Railway) was completed in 1854, the hinterland of southern Georgian Bay became hitched to both the world economy and the developing transportation network with connections to Lake Superior and beyond.

Each lock at Sault (Soo) Michigan had a lift of just over three metres (about ten feet). Steamers and schooners carried grain, ore, package freight and passengers from both American and Canadian ports around the whole Great Lakes basin. After 1870 there was pressure to construct a Canadian lock to insure clear passage for Canadian vessels. Courtesy of the State Archives of Michigan, Negative No. 05595.

A growing urban population in the eastern United States sent grain prices even higher. In addition, an insatiable demand for lumber in Chicago and an irresistible pressure for new farmland from immigrants turned the southern shore of Georgian Bay into a tumultuous real estate market. Speculators and land agents promoted the region with claims that enticed prospective farmers from eastern Ontario as well as immigrants from Britain.

On June 18, 1855, a set of two locks on the St. Mary’s River at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, allowed the first steamer, the Illinois, to pass upbound into Lake Superior.7 The event opened the lake to serious commercial activity. The two locks with a lift of twenty-one feet allowed ships to bypass the rapids that blocked easy passage between Lake Superior and the lower water levels of lakes Huron and Michigan. The cities of Detroit and Chicago, as well as Collingwood, were now directly connected to Lake Superior destinations. Emigrants, freight and mail had an efficient course to the ports of Duluth and Thunder Bay, and to the new mines on the shores of Superior and to western North America.

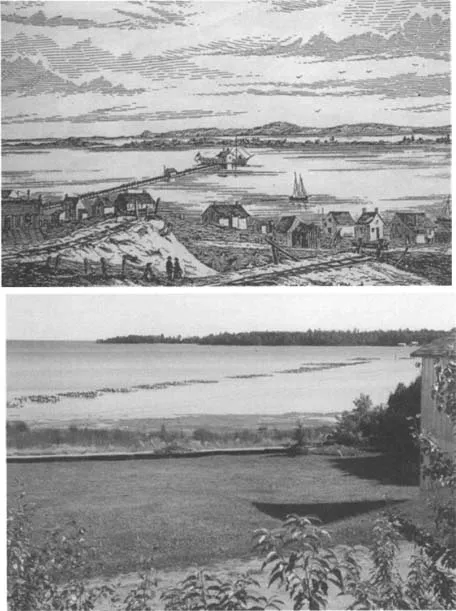

Top: This sketch of Bruce Mines by William Armstrong (1822–1914) originally appeared in the Canadian Illustrated News on December 23, 1871. The original is at the Library and Archives Canada. The Frances Smith was a regular visitor to Bruce Mines after 1871. By that time the economy of the area had shifted from mining to agriculture. However, whenever there was a delay at the dock passengers made a point of walking to the old mine, still an attraction for today’s visitors. Courtesy of Bruce Mines Museum. Bottom: The Bruce Mines dock as it looks today, a reminder of the time when the town was a supply centre for shipping copper to Great Britain. Photo by Scott Cameron.

In the 1840s, the Montreal Mining Company began production of copper at its new mine at Bruce Mines on the North Channel, the body of water that stretches from Killarney to the Sault. The rich copper ore was shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to Wales for smelting. Initially, some ore was sent across lakes Huron and Erie by schooner, but increasingly Collingwood, as the terminus of the new railway, became the important hub for copper export activity. The growing town also became the supply depot for Bruce Mines and for prospectors attracted north in search of new mineral deposits.

The timber business in Michigan was fully matured by 1855, and entrepreneurs began to look to the vast reserves around the east coast of Georgian Bay, from Penetanguishene to Parry Sound and as far north as the La Cloche Mountains. Two decades later, estimates of twenty-four billion board feet of lumber in the area near the Spanish River alone attracted dozens of Canadian and American investors.8

By 1854 the Royal Mail for all points north and west in Canada converged at the port of Collingwood. Competition for mail contracts was fierce. As well, the communities along the southern shore of Georgian Bay from Wiarton to Meaford were moving beyond the “roughing it in the bush” pioneer stage and onto the cusp of a period of anticipated commercial and industrial prosperity. The growing villages put pressure on the transportation system for agricultural necessities, dependable business communications and regular mail delivery. Small town businesses became the bread and butter of the evolving lake traffic.

One of the first steamboats on Georgian Bay, the Penetanguishene (1833),9 was described as “a wretched little boat, dirty, and ill contrived.”10 By the 1850s larger and faster ships replaced both it and the 125-foot Gore (1838). Sidewheel steamers like the Ploughboy (1851), the Kaloolah (1852) and the propeller Rescue (1858) were either built for, or migrated to, Georgian Bay in order to participate in the opportunities created by the economic boom. Scores of schooners worked the bay with cargoes of lumber and grain destined for Toronto by way of Sarnia, the Welland Canal and Lake Ontario. Others sailed only from Georgian Bay to Chicago. Tools, cookstoves, ploughs, whisky, dry goods, salt and manufactured goods poured into the ports of Collingwood, Meaford, Cape Rich and Sydenham11 to support the early settlers moving into the surrounding townships. Lumber, peas, apples, fish and potash intended for markets as far away as New York and Britain returned in the emptied holds.

The primitive roads of 1855 were almost impassable in spring and fall. Deep ruts, raging streams and bogs near the shore meant that heavy freight could not be moved easily on the muddy and poorly constructed roads. Even roads that were passable in dry summer and frozen mid-winter were narrow, rutted and ungravelled. Between spring breakup in April and freeze-up in early December, the water hig...