![]()

CHAPTER 1

Toward a Canadian Naval Service, 1867–1914

Roger Sarty

It has been in contemplation to organize gradually a naval force, and we believe the time has come now . . . [W]e should be prepared, we should be anxious to relieve the mother country from the responsibility of defending our coasts and our harbours. . . . [W]e should take up seriously the question of local defence of the sea . . . we should follow it on the lines of local autonomy . . .

—SIR FREDERICK BORDEN, MINISTER OF MILITIA AND DEFENCE, HOUSE OF COMMONS DEBATES, 10 FEBRUARY 1910

The establishment of the Canadian Navy is remarkable, both for the lateness of that event and the meagre results. Canada, whose motto translates as “from sea unto sea,” has the longest coastline of any country. Even so, the navy was not founded until 4 May 1910, nearly 43 years after the creation of the modern Canadian state on 1 July 1867. Despite growing tensions in international relations, the new service was so politically controversial that it was nearly stillborn, and Canada remained desperately unprepared when Europe descended into war in the summer of 1914.

The paradox arose from Canada’s development as a part of the British Empire. The empire owed its creation and expansion to Britain’s Royal Navy, the world’s most powerful from the late seventeenth century until the beginning of the 1940s. Britain was able to seize France’s colonies in North America during the Seven Years’War because the Royal Navy’s predominance in the Atlantic allowed the British to mass their forces for the assaults on the main French strongholds of Louisbourg in 1758 and Quebec in 1759, while cutting off New France from reinforcements. Britain’s own American colonies were able to secure their independence in 1783 because a European alliance led by France temporarily achieved the advantage over the Royal Navy.Yet, the Royal Navy turned back an American invasion of Canada in 1775–76, and again prevented the conquest of the remaining British North American colonies when the United States repeatedly invaded in 1812–14. It was the menace the Royal Navy posed to the U.S. seaboard from bases at Halifax, Bermuda, and Jamaica that ultimately secured Canada from American Manifest Destiny during crises in the 1830s, 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s.

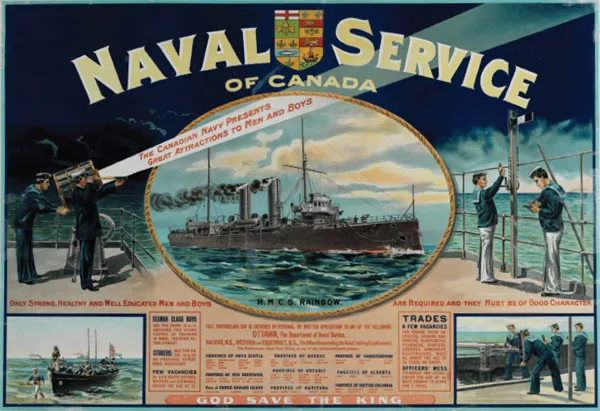

Canadian War Museum 19940001–980

The RCN’s first recruiting poster.

Military dependency upon Britain and cheap defence were foundation stones of Canada.The primary cause of the revolt of the American colonies in 1775 had been British efforts to tax the colonists to pay the enormous costs of the British forces that had conquered Canada in 1754–63 to secure the American territories against French incursions. Thereafter, Britain did not generally attempt to recoup the costs of its forces on colonial service, particularly in the case of Canada whose French-speaking inhabitants viewed the British military as occupiers, not protectors.

At issue were land, not naval, forces. Since the American invasion of 1775, the southern border of the northern colonies had to be protected by fortifications, garrisoned by troops from Britain’s small, expensive professional army, to prevent the territories being overrun while the Royal Navy conducted offensive operations against American trade and coastal cities. In the 1840s and 1850s, the British government responded to political unrest in the northern colonies by granting self-government in internal matters, but also began to cut back the garrisons sharply, linking self-government to greater responsibility for self-defence—and incidentally, relief to the British treasury.When the American Civil War of 1861–65 threatened to engulf the colonies, the British Army massively reinforced the garrisons, but the steep cost of this effort was an important reason why the British government supported confederation of the colonies to create the Dominion of Canada in 1867. Britain withdrew all of its troops from the interior of the new country in 1871, and defence of the border became the responsibility of the Canadian militia, a force of some 40,000 part-time volunteers administered and instructed by a “permanent force” of full-time professionals that numbered no more than 1,000 until the early 1900s.

The ultimate guarantee of Canadian security was still the Royal Navy. Even the most cost-conscious British politicians admitted that protection to Canada was the incidental product of Britain’s need to control the North Atlantic, the heart of the seaborne trade that was Britain’s lifeblood. Britain retained its strongly fortified dockyards at Halifax and Bermuda, together with the permanent naval squadrons that operated in the western Atlantic and the eastern Pacific, including the new British dockyard at Esquimalt, British Columbia. British Army garrisons of about 2,000 troops remained at Halifax and Bermuda, and British troops later developed defences at Esquimalt. Canadian leaders of the late nineteenth century, believing that the British naval presence persuaded the United States not to attempt domination of Canada, avoided naval defence undertakings for fear these would encourage British cutbacks.

Department of National Defence HS89-0198-19

The possibility of a distinctly Canadian path to naval development emerged in the late 1880s when an Atlantic fisheries dispute with the United States brought the government to organize a fisheries protection service of six to eight small armed vessels to arrest American fishing craft that illegally entered Canadian territorial waters—waters within three nautical miles (approximately six kilometres) of shore.The vessels and their crews formed part of the Canadian Department of Marine and Fisheries, whose principal responsibilities included lighthouses and other aids to navigation and the regulation of civilian shipping. Ex–Royal Navy officers who the Canadian government hired to run the service and British officials in Canada saw the possibilities for developing the fisheries protection service into a naval force.The Admiralty was not interested. Rapid progress in technology saw the development by the late 1880s of large, fast, long-ranged steel-built warships, renewing confidence that the Royal Navy’s main fleets, centrally controlled from London in their global deployments, could, just as in the days of sail, intercept any but the smallest enemy forces. In 1887 the Australian colonies and New Zealand began to make annual payments to the Admiralty to subsidize the assignment of additional Royal Navy cruisers to their waters.

By the late 1890s the idea that the empire should become a more tightly organized military alliance to meet sharply increasing competition among the great powers won widespread support in Britain and all the self-governing colonies. When in 1899 Britain went to war with the Boer republics in South Africa, the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier, Canada’s first French-Canadian prime minister, was caught between demands for participation from English Canadians and strong resistance from French Canadians. Laurier’s compromise, to send contingents comprised solely of young men and women who volunteered to serve, by no means healed the rift in opinion.The brilliant Liberal member of parliament (MP) and journalist Henri Bourassa broke with the prime minister to campaign against military cooperation with Britain; he especially warned against naval initiatives because of the Admiralty’s doctrine of centralized control of the empire’s naval defences. Even Bourassa admitted, however, that there was a need for fisheries protection.

Laurier tried to square the political circle by casting military reforms as national defence measures that enhanced Canadian status, but also strengthened the empire by relieving Britain’s over-stretched armed forces of commitments in North America. He was prepared to undertake naval development of the fisheries protection service, and in 1903–04 the government procured the CGS Canada, a 910-tonne steamer built to naval specifications. Further naval initiatives, however, were put on hold in December 1904, when Britain, as part of its efforts to concentrate its armed forces closer to home to meet growing dangers in Europe, closed the dockyards at Halifax and Esquimalt, and announced that the Royal Navy squadrons that had operated on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America would be withdrawn.The defences at Halifax and Esquimalt would still be needed to provide secure operating bases for the British fleet, so Laurier seized the opportunity for a nationalist initiative warmly endorsed by both French and English Canadians, by offering to take full responsibility for the permanent garrisons and fortifications at both Halifax and Esquimalt.This gesture, which the British gratefully accepted, entailed tripling the size of the 1,000-man permanent land force, and was the main reason why the land militia’s annual budget doubled to some $6 million a year.

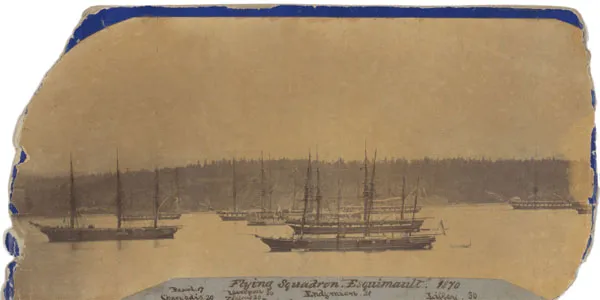

Esquimalt Naval Museum VR991.29.1

The Royal Navy’s Pacific Flying Squadron anchored in Esquimalt Harbour, 1870, including (bottom left) then-HMS Charybdis.

Laurier still maintained that the fisheries protection service was the “nucleus” of a navy, but any grander schemes were effectively scuttled. Further development came as the result of scandal. Early in 1908 a royal commission reported that the Department of Marine and Fisheries was hopelessly inefficient. Laurier and the minister, Louis-Philippe Brodeur, a lawyer whose early career in Quebec nationalist politics gave him credibility in that province, cleaned house immediately. Georges Desbarats, an engineer in the department with a reputation as a talented administrator, became deputy minister. Laurier had already met, and been impressed by, Charles E. Kingsmill, a Canadian who had entered the Royal Navy in 1869 at the age of 14 and risen to the rank of captain. Kingsmill accepted the invitation to take charge of the government’s marine services. Promoted rear-admiral on his retirement from the Royal Navy, his professional credentials were on an entirely different plane than those of his predecessors, who typically had left the British service as very junior lieutenants.

The Conservatives, led by Robert Borden since 1900, were no more anxious than the Liberals to confront the contentious naval issue.They contented themselves with periodically tweaking the government to get on with naval development of the fisheries protection service. In January 1909 Sir George Foster, one of Borden’s senior colleagues and a former minister of marine and fisheries in the Macdonald era, placed on the order paper for the new session of Parliament a resolution that “Canada should no longer delay in assuming her proper share of the responsibility and financial burden incident to the suitable protection of her exposed coast line and great seaports.”The resolution had been inspired by an Australian initiative to end the annual subsidies to the Royal Navy, and instead revive their own naval organization. The Admiralty, holding firm on the need for British control of seagoing warships, allowed that any colonial service could acquire the improved coastal torpedo craft, including destroyers and submarines, that had been developed since the late 1880s.The torpedo craft would make local ports more secure to support strategic deployments of the British fleet.

Before the Foster resolution came up for debate, the politics of the naval issue were transformed by developments overseas. On 16 March, Reginald McKenna, First Lord of the Admiralty in Britain’s Liberal government, requested additional funds for battleship construction, citing evidence of acceleration in Germany’s building program. In 1905–06 the Royal Navy had stolen a march on competitors by building the revolutionary His Majesty’s Ship (HMS) Dreadnought, the first large (16,270-tonne) modern battleship to carry a uniform battery of 10 of the heaviest guns—12-inch—in place of the mix of a few heavy and other lighter guns in existing 9,100-tonne designs. Now, intelligence suggested, Germany might be able to match Britain in numbers of its own “dreadnoughts” as early as 1912.

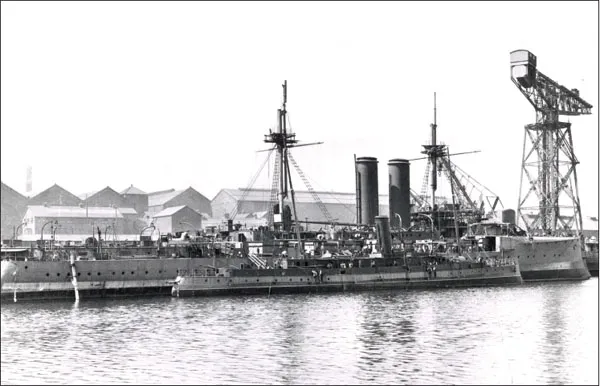

Directorate of History and Heritage 0-233

The future CGS Canada fitting out in the Vickers yard at Barrow-in-Furness, 1904, lying outboard of HMS Dominion, also still under construction and whose first captain in 1906 would be Captain C.E. Kingsmill, Royal Navy (RN).

The news that Britain’s maritime supremacy was so seriously challenged by a single power exploded like a “bomb shell,” in the words of one contemporary Canadian commentator. New Zealand quickly offered to make a special, one time payment to the British government sufficient to build one or, if necessary, two dreadnoughts. There were widespread demands among English Canadians in both the Liberal and Conservative parties that Canada do the same, creating a nearly identical problem for Laurier and Borden, both of whose French Canadian supporters had grave doubts about any form of naval initiative. In the face of these common problems the parties worked out a compromise in a single day of debate of Foster’s resolution, on 29 March 1909. In a new resolution supported by both parties, Laurier promised the “speedy” organization of a coastal defence force in consultation with the Admiralty on the model of the Australian scheme (that, of course, he had always insisted was built on the example of Canadian local defence by forces under Canadian control). Laurier’s draft ruled out any cash contributions to the British government, but at Borden’s insistence the final version rejected only regular contributions and thus did not specifically rule out a future one-time “emergency” payment.

A fe...