![]()

Chapter 1

THE BYGONE AGE

In a few centuries, or even in a few generations, the first fifty years of Canadian life, the ways and means — the makeshifts of the men who took hold of the bush and made it into an inhabited and cultivated country — will be an interesting study. Then people will regret that so few materials remain for the illustration of the formative period of the country. I am glad that now in this year 1900, there are several local Historical Societies — most of them newly begun — to do something toward preserving a memory of our “olden times.”

The coming of a family from Europe to America, will always with us be the beginning of the family history. It is not possible, frequently, to go back farther: but there is a solid beginning, that, “in the year 18_, my ancestor, Mr. ____ ____, from such a place in the old world, emigrated to these shores.” And it is difficult for us to realize the fact, that we ourselves have been living, and are living, in the formative period of our country’s history.

Every country has its “heroic age.” The first dwellers in most European lands were the veriest barbarians, with little else than their bare hands to begin the battle of life, and, until touched by some influence from without, with little or no apparent desire to improve their surroundings. Their “heroic age” lasted for centuries, and has left many memorials. We, in Canada, began under different conditions. Civilized and enterprising men came to a howling wilderness it is true, yet with the ambitions and feelings of free men, and determined to conquer the circumstances of their surroundings. Their “heroic age” lasted more than a generation — till the old log house gave place to a dwelling of painted clapboard — or perchance to that of brick or stone; till the “woods” had melted away, even to the stumps that had been left behind; till the church and the school, and the Agricultural Society, the town, the fair, the railway, and lastly, the daily paper, took their places everywhere.1

Perhaps for Canada within the Lakes, that is the region bounded by the three great lakes of Ontario, Erie, and Huron — the garden of the New Dominion — the bygone age may be said to have ended with the coming of the railways, say 1855. As long as the “first settlers” remained in a township, that township was still under the influence of their ideas and habits — it was still for them in its “golden age” — yet more golden now to look back upon, through the vista of fifty years, than when it was reality!

Mosquitoes

A well-to-do, hale and pleasant old gentleman of Danville, Quebec, Mr. Goodhue,2 told me that when he was a boy there, sleeping in the “chamber” of a small log house, close up under the shingles, with the “bush” all around them, the torment of the mosquitoes was something not to be imagined by people of the present day. I am reminded of a night I once passed, sleeping on the ground, up the Spanish River in Algoma. The heavy sultry air was vocal with them, and the Scotch plaid, inside which I sweltered and rolled about, was punctured everywhere with their barbs. They were certainly the perfection of skirmishers! I once called at the house of a German settler, in Brant Township, Huron [County], just as he came in for his dinner, begrimmed with “logging” on a new clearing. The day was very hot, and I asked him if he did not often wish that some of those numerous and useless Grand Dukes of his fatherland could be made to take their turn at logging? “Yaas!” said he, with a grin of anticipated satisfaction, “and let dem fight der mosquitos!”

When we were little boys — my brothers and I — our necks, and feet and hands were well-blistered by the mosquitoes, and on one occasion my father said that he would have to get another barrel of salt: “Yes,” said one of the younger boys, “we must have another barrel, to salt the bites!” For we had found some alleviate in rubbing salt on the wounds made by the mosquitoes.

Hardships

Bush life became a dread reality when there was nothing to eat in the house, and none of the neighbours had anything to lend, and there was no money to go off and buy. Mr. Gilmour, of Muskoka, told me of his dragging a bag of flour fifteen miles over the snow in a deerskin; the hair lies back with so strong a “pile,” that Norwegian settlers put a patch of it on the bottom of their “scoots,” or long wooden snowshoes, to prevent slipping back in ascending hills. John Brown, of Caledon, told me of “backing” flour, carrying it on his back — twenty miles across from “Yonge Street,” where was the nearest mill.

One poor fellow, an English settler named Barnes, whose widow I have often seen, actually died of starvation, in the Township of Sullivan, thirteen miles south of Owen Sound.3 The little handful of flour or meal in the house was painfully doled out to the children, and he tried, for two weeks, to support his own life on cow-cabbage and dandelion, boiled into greens. Failing to support life thus, after a bitter struggle, he lay down and died.

A farmer’s wife in Caledon, Mrs. McArthur, told me that she had gathered the young leaves of the basswood, and boiled them for greens, in dire distress for bread. But for the aid of potatoes, it is difficult to see how families could have lived at all. And even then, the old-fashioned species of potatoes were so late in ripening, that the crop was of little use till the summer was well-nigh over. The man who introduced the “Early Rose” potato, a number of years ago, was a greater benefactor than he knew. The old “Merinos,” and “Meshannocks,” and “Kidneys,” and “Cups” were all good enough potatoes, but we don’t want to wait till well into August, before we can begin using them! With the Indians, the Spring is the starving time, and I thought one spring, as I was vainly endeavoring to exterminate a bed of Jerusalem artichokes4 from my garden, what a blessing it was that the Government could bring their improvident wards the Indians, at the slight expense of sending an agent with a few bushels of artichokes, to plant a few of the rocky islands of Lake Huron. Once there, they would be always there, and it would tide the Indians over till their earlier potatoes were ready to dig.5

A Potato Story

An adventure of the lads of Inverness, Megantic County, Quebec, will illustrate the raising of potatoes. I had it [the story] from Mrs. Joseph Wallis of Etobicoke. The Inverness settlement was made, fifty or sixty years ago, by a large immigration of Highlanders from the Island of Arran,6 under the leadership of “Captain” McKillop.7 They lived under blanket tents for two months, till they got up houses for shelter. At last, such fortune as a very stony and ungrateful land — but plenty of it — could give them, began to smile on their prospects; and they were anxious to have a regular minister of the Gospel to settle among them — Captain McKillop having till this time led their public devotions.8 They induced a good man to come out from the Highlands, and to cast in his lot with them, promising him that though they could not give him much money, they would get him a hundred acres of land, and help him clear it up and cultivate it.9

This arrangement had gone on for some years; the minister’s farm was gradually getting cleared up, and his crop, principally potatoes, was regularly “put in” by the flock. But, one spring, some of the young men demurred to this imposed task. They said “such and such families, with sons, had so many days’ work to do at the minister’s, while other families, where there were only girls, escaped the impost, and it was not fair!” The girls, however, heard of it, and the reason assigned. Soon they plotted together, and two or three mornings after, twelve of them with hoes over their shoulders, marched two and two, to put in the minister’s crop! “And were you one of them?” I asked the elderly lady who told me. “No,” she said, “I was not then old enough, but my eldest sister was one of the number.” “And did they finish the work?” I enquired. “Oh,” she said, “it was never so quickly nor so well done! And there never was any trouble again, as long as the minister lived. As soon as the word got round the settlement that the girls were at work, all the young men turned out to help them!”10

Makeshifts

When a boy, I heard William Kyle, an old storekeeper in St. George, tell of a man named Jackson, who, nearly half a century before that had married against the wishes of his friends, “and,” as the story was told, “just took his wife under his arm, with his gun and his axe, and went back into the Bush.” He camped at the forks of a river, forty miles back from the St. Lawrence. When winter came, he brought a fat deer in from the forest, strapped a good pack of furs upon a light sled he had made, kissed his wife, and started for Montreal on the ice of the river. There, he exchanged his pelts for “store goods,” and he returned much heavier laden than when he went. His troubles were now over. He had plenty to eat and wear, and his clearing yearly got larger. Some other settlers began to find him out, and to squat down beside him, and when my old friend knew him, he was the “Squire” of the place with large mills, and other property.

No wonder, considering the tools they had to work with, and the frequent lack of skill in those who used them, that the log huts were sometimes of the roughest and smallest. I remember riding southward from Owen Sound, down the “Garafraxa Road,”11 and seeing the axe, every time it was uplifted, of a settler who was chopping on his woodpile at the back door — I saw the axe, over the roof of the house!

I have seen the floors made of thick-hewn basswood — and basswood will warp! Doors, also, of split cedar, with creaking wooden hinges. I have myself made both hinges and latches of wood. But of all the contrivances of those days, the most comical appurtenance to a log house was a “one-legged bedstead.” It will be seen, that if stout green poles from the woods are inserted in holes bored in the house logs, at one corner of the house, so as to answer as bed rails, there is only one corner of the bed which needs support of a leg! Often the two farther corners of the house are thus occupied; for a log house with up-and-down board partitions, [it] is the first stage toward opulence and luxury, not always obtainable by the poor settler. Reverend John Wood told me of once, with a brother minister, sleeping in the house of a Scotch settler, in whose improved house of after years I myself have more than once spent the night. There was then but one room for both family and guests. The housewife, on their expressing a desire to retire for the night, remembered that there was something outside she had to see about, and the clergymen made use of the opportunity thus purposely afforded them, to hastily unrobe. One, however, hesitated and fumbled, and the other had to come to his rescue. “Now, Brother!” he said, in a vigorous whisper, as he held up a quilt at arm’s length in front of the bed. The screen satisfied the demands of civilization, and all was quiet in the corner before the reappearance of the honest matron.

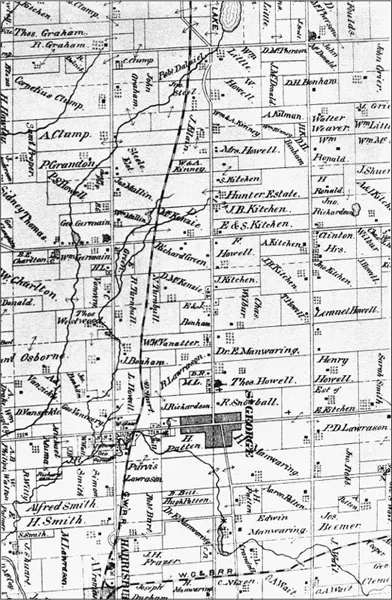

Detail from a map of South Dumfries Township, Brant County, showing the location of St. George.

From the Historical Atlas of Oxford & Brant Counties (1875) 89.

Schoolmasters

In those days, people had the desire to educate their children, but the opportunities were few. The elder sons and daughters of many a family had little education to fall to their share, though it was always considered a disgrace to be unable to read and write. I, myself, was only at school for two “quarters,” from the age of ten to eighteen. In many cases it was that the work of the elder children was needed to build up the family fortunes, when with justice to themselves they should have been at school. And so it came about, that in the winter many young men and young women would get a “quarter’s ‘schoolin,’” who would not think, nowadays, to be seen at school.12

I have often thought of the justness of the old Hebrew rule of inheritance, that the oldest son should have a “double portion,” and the younger son’s single portions from their father. The elder son had often, as in our...