CHAPTER 1

The Grand Old Lady of Shuter Street

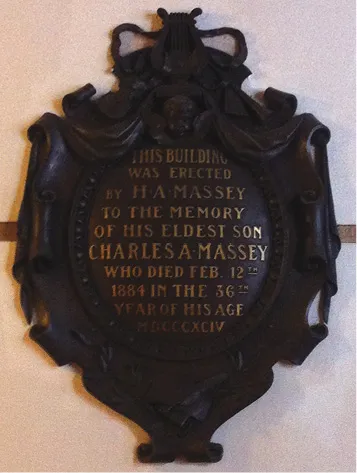

The Masseys are among the great Canadian families, with a governor general (Vincent) and a distinguished film actor (Raymond) among their better-known progeny. Less well known than either of these men is their grandfather, Hart, who parlayed his father’s Newcastle foundry into one of the continent’s foremost farm implement manufacturers, and became in the process one of Toronto’s leading philanthropists. Along with the Fred Victor Mission and a number of church charities, Hart bankrolled the construction of what would come to be known as Massey Music Hall, one of North America’s finest nineteenth-century venues for what H.L. Mencken called “the tone art.” The building cost just in excess of $150,000 and Hart Massey offered it as a magnanimous gift to the City of Toronto, named to honour his son Charles Albert Massey, who had died during a typhus epidemic in 1884 at the age of 36.

Plaque honouring Charles A. Massey in the lobby of Massey Hall.

Photo by Alexandra Basen.

Until the 1920s, Massey Hall was said to be the only place of its kind in Canada, designed primarily for the presentation of musical performances. With its cramped site and unprepossessing brick facade — more handsome but costlier stone had been proposed but was ultimately rejected — architect Sidney R. Badgley’s landmark edifice hardly invited an aesthetic comparison with New York’s Carnegie Hall, Boston’s Symphony Hall, or Cincinnati’s Music Hall, all of which were built within a couple of decades of each other. Toronto’s was a utilitarian structure. When the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada ornamented the facade to mark the centennial of Massey Hall with a commemorative plaque, the inscription read, in part: “Although criticized for its plain exterior, the concert hall has earned widespread renown for its outstanding acoustics.”

Those acoustics were put to a dramatic test in April 1961 when one of Europe’s noted physicists, Professor Fritz Winckel of Berlin, pulled out a .38-calibre revolver and fired a blank cartridge toward its ceiling arches. Consulting his stopwatch to assess the reverberation time, he proclaimed Toronto’s major concert hall one of the finest in the world. Though this single-shot diagnosis makes for a good story, Winkel’s declamation was based on more than mere gunplay. He had taken measurements and listened to the Toronto Symphony Orchestra in rehearsal, finding more than a few reasons to share the enthusiasm for the place expressed by his friend, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra’s celebrated post−Second World War conductor Herbert von Karajan.

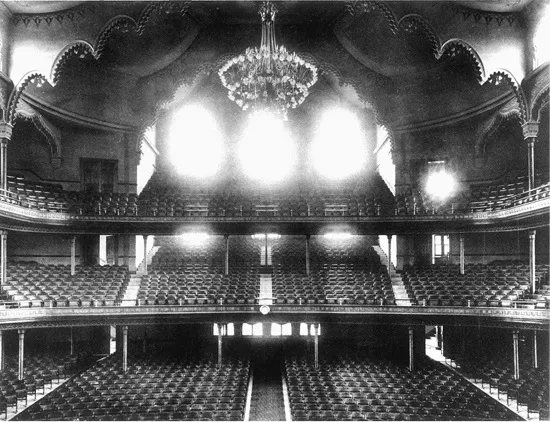

The interior of Massey Hall as it was in the late 1890s.

Courtesy of the Ontario Archives.

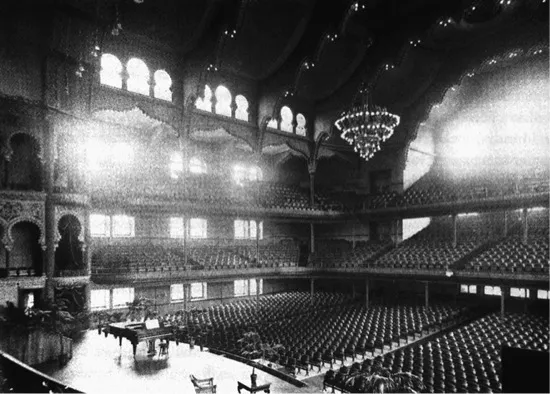

Light (and noise) flooded into Massey Hall through the original stained glass windows.

Courtesy of the National Archives of Canada.

In Intimate Grandeur, William Kilbourn details the sheer improbability of Hart Massey’s enterprise, characterizing the Toronto of 1894 as “a provincial, Protestant, philistine city of 180,000 inhabitants,” and Massey himself as “a tight-fisted, quarrelsome, opinionated old autocrat.” But the fearsome disposition was offset by a philanthropic bent that Kilbourn roots in Hart Massey’s Methodist upbringing. Whatever the explanation, on a sunny mid-June evening in 1894, he and his carriage-driven family joined Governor General Sir John Campbell Hamilton Gordon, Earl of Aberdeen, along with anyone else fortunate enough to procure one of the 3,500 available seats, to face an orchestra and choir of 750 voices performing Handel’s Messiah at Massey Hall’s grand opening.

Frederick Torrington, the conductor of that first performance, can be seen to this very day gazing from a framed portrait in the Gerstein Library of the University of Toronto’s Medical Sciences Building. The acknowledged leader of the city’s classical-music community in the late nineteenth century, Torrington contributed mightily to Toronto’s reputation as a city of choirs. The red-brick building at the corner of Shuter and Victoria Streets soon became the prized destination of the most ambitious among them.

Architect Sidney R. Badgley was not without credentials for serving Torrington’s ambitions for music in Toronto. A Canadian based in Cleveland, he was the designer of a number of auditorium-style Methodist churches. His initial plans for Massey Music Hall, as it was called before its name change in 1933, included a setback from Shuter Street and the incorporation of ground-floor shops to flank the main entrance. Unfortunately for Badgley’s plans, Hart Massey refused to pay the requested price for the lot to the south of the present site. Torrington’s desire for a shoebox shape characteristic of some of Europe’s finest homes for music had to be modified in favour of Badgley’s preference for a squared space with curved, horseshoe-shaped galleries, reminiscent of his church designs.

In its present well-worn state, it is less easy to appreciate the extravagant Moorish features Badgley envisaged for the hall’s scalloped interior, with its multicoloured decorative details and its art nouveau stained glass windows. The windows still exist, and although a few have been revealed in recent years, most still await their rediscovery behind coverings installed over the decades to mask the noises of an increasingly motorized and congested urban core. In an interesting week from the hall’s later history, adjoining streets had to be temporarily closed off by special permission of Toronto’s mayor when Igor Stravinsky came to town to record some of his music with Elmer Iseler’s Festival Singers for CBS Records. Sound isolation, a necessary and expensive feature of modern concert hall construction, barely concerned architects during the days of horse-drawn buggies.

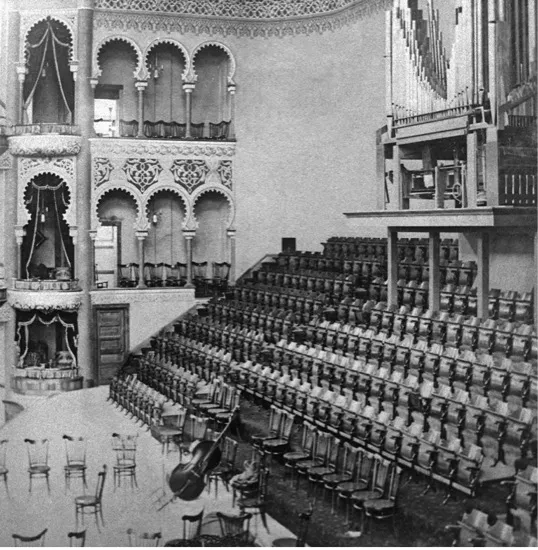

A strict moralist who disliked the theatre almost as much as he disliked alcohol, Hart Massey never anticipated the range of activities his civic gift would eventually accommodate. Despite its lack of theatrical wings or fly space, short decades after its founder’s demise Massey Hall was welcoming visiting vaudeville acts, the ballet troupe of Anna Pavlova, and even the famed boxer Jack Dempsey. If Badgley had a crystal ball with which to peer into Massey Hall’s future uses, or had he been given more space to design the hall as he had imagined, then he might have better accommodated people on both sides of the (occasionally present) footlights. Lobbies were cramped and dressing rooms minimal, and the fact that about 4,400 people (counting performers and staff as well as audience members) managed to squeeze into the building on opening night, June 14, 1894, still amazes a twenty-first-century observer.

Hart Massey did not long survive the triumph of opening night. Unwell even at the time of Massey Music Hall’s public debut, he died on February 20, 1896. The lights in the Massey family box suddenly went out that evening during a performance of Haydn’s The Creation. At its end, Frederick Torrington, who understood what had happened, turned to the audience to make an announcement. As everyone stood in silence, the orchestra brought the evening to its sad conclusion, playing the “Dead March” from Handel’s Saul.

The original Massey Hall stage and private boxes.

Photo by B.W. Kilburn, 1894. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library.

Although the years ahead witnessed financial ups and downs, the hall’s trustees strove to meet the conditions of Hart Massey’s deed of gift: to make the hall available for the “musical, educational, and industrial advancement of the people, the cultivation of good citizenship and patriotism, the promotion of philanthropy, religion and temperance, and for holding meetings and entertainments consistent with any of the above purposes.” Orchestras arrived from Buffalo and Chicago; the noted evangelist Dwight Moody held revival meetings. Even Lady Aberdeen descended from the box she had shared with her husband on opening night to lecture on “The Present Irish Literary Revival.” A full day’s rent of $90 in summer and $110 in winter made it a less costly venue than many of its American counterparts. On the other hand, a depressed economy discouraged higher rents and there was no civic subsidy to cover deficits. It did not take long for the trustees to realize the importance of drumming up rental business.

The hall’s management went into partnership with a succession of presenters, as early as 1901 expanding their vision for the hall to include the sinful art form known as opera in order to entertain the Duke of Cornwall and York and his consort (the future King George V and Queen Mary). Aside from taking out a couple of rows of seats to accommodate an improvised orchestra pit, there was little the hall’s management could do to disguise its unsuitability as an opera house. Even so, in part because of its large capacity, it became one of Toronto’s preferred operatic venues during its first half-century, with the touring San Carlo Opera crowding the likes of Gaetano Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and even Giuseppe Verdi’s grandiose Aida onto its concert-scaled stage.

Massey Hall’s suitability as a home for large-scale choral performances was established on opening night, so there was little surprise when, in 1894, the newly formed Toronto Mendelssohn Choir took up residence under the direction of its Elmira-born, Boston- and Leipzig-trained founding maestro, Augustus Vogt. Such was Vogt’s early success in setting a high standard for his choir that it soon found itself collaborating with orchestras from Pittsburgh and Chicago and receiving rave reviews for its appearances at Carnegie Hall. Musical America even stated that “the Mendelssohn Choir represents in the realm of choral music what the Boston Symphony stands for in its domain.”

Although Massey Hall and its resident choir were highly regarded, bills still had to be paid and that meant appealing to a broader public than admirers of choral music in general and Felix Mendelssohn in particular. There were limits, however. After Isadora Duncan, the high priestess of modern dance, performed barefoot in 1909, negotiations were cancelled with the next modern dance ensemble exercising such cavalier disdain for the local audience’s penchant for modestly attired performers. It seemed somehow less déclassé when the Scottish singer-comedian Harry Lauder arrived a few years later with his “amazing, football-playing dogs.” And there was apparently no significant objection, in less enlightened times, to Jacob Adler portraying Shylock in The Merchant of Venice in Yiddish. Massey Hall even anticipated Roy Thomson Hall’s future role as a part-time movie theatre, with runs of D.W. Griffiths’s Birth of a Nation and Intolerance packing the galleries. The music hall had become home to a wide range of community activities, from religious services and gatherings of Boy Scouts to a brief stop, courtesy of Eaton’s department store, of a red-suited gentleman bearing gifts.

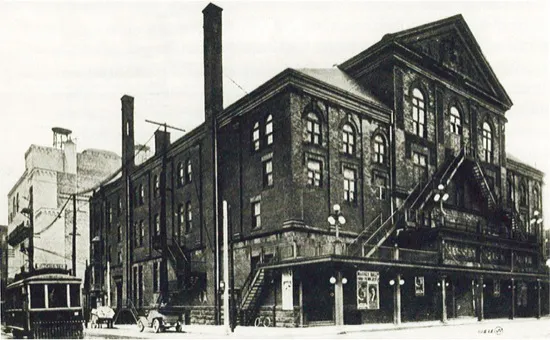

Massey Hall, 1914.

Courtesy of the Toronto Reference Library.

Community events notwithstanding, Massey Hall was Toronto’s prestige public venue. The tumultuously welcomed Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII, spoke there during his November 1919 visit. Less than a year later, no less an amateur pianist than Lady Eaton accompanied the Guelph-born Edward Johnson in a charity song recital — Sir John Eaton ordered the stage specially scrubbed for the occasion and filled with potted flowers and plants from the family estate. A whole roster of celebrity speakers followed, ranging from the controversial philosopher Bertrand Russell to Howard Carter, the archaeologist who discovered King Tut’s tomb.

The first Toronto Symphony Orchestra was born in 1908 out of an ensemble organized by Toronto Conservatory of Music director Dr. Edward Fisher and led by pianist/conductor Frank Welsman. The financial and manpower demands of the First World War eroded support for the ensemble, which disbanded in the summer of 1918. By 1923, mainly thanks to the efforts of violinist/conductor Luigi von Kunitz, Massey Hall once again became Toronto’s regular home for symphonic music. Initially known as the New Symphony Orchestra, the eventually renamed Toronto Symphony Orchestra offered twilight concerts at first so its players could dash off for the pits of the city’s numerous vaudeville and movie houses, which paid better and more frequently than the classical orchestra’s less frequent concerts. Under music director von Kunitz and his successor Ernest MacMillan — who would later become the first musician from the British Empire to earn a knighthood — the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s concerts multiplied and its season lengthened. The hall had become a home (or at least landlord) to one of North America’s major orchestral ensembles.

It is sometimes forgotten that this important role did not prevent Vincent Massey and some of his fellow trustees from considering the hall rundown, outdated, and possibly in need of replacement by the late 1920s. The Great Depression, the popularity of radio, and the arrival of sound films nixed that notion in favour of a substantial renovation in 1933. The number of seats was reduced from 3,500 to 2,765 and the lobby spaces were expanded, with the Massey family once again subsidizing the cost. Vincent Massey had even accepted the presidency of the board of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.

Although the TSO was claiming a greater number of evenings per year on stage at Massey Hall, there remained as late as 1948 the need to rent the hall for additional events to pay the bills. Perhaps the most surprising of these were the boxing and wrestling matches fought on stage, including a 1919 bout featuring future heavyweight champion of the world Jack Dempsey. Notable visitors of a more artistic bent included George Gershwin, playing his Rhapsody in Blue, and the ambitious Toronto director/playwright Herman Voaden, staging T.S. Eliot’s new verse play Murder in the Cathedral, with music by the city’s foremost composer, Healey Willan, sung by his own Church of St. Mary Magdalene Choir.

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra plays Massey Hall, 1926.

Photo by Brightling. Courtesy of the Toronto Public Library.

William Kilbourn describes the quarter-century from 1931 to 1956 as “Massey Hall’s golden age,” with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra under Ernest MacMillan and the Toronto Mendelsso...