![]()

1 Go for Broke

Bracknell, England, 2005

Under an hour from London, England, by train is a town, Bracknell, from which I continue to what Carolyn Cassady described as “a real woodsy road.” Here among small postwar homes is a lime-green bungalow opened to me in May 2005 by this tiny woman, still attractive at eighty-two.

Famously, she was the lover of both Neal and Jack — and no shrinking violet upon moving to England in 1983. Well recognized here for marriage to that supremely free-spirited man, she’s now close to a blithe Irish rocker named Bap Kennedy. The bathroom is marked by a sign reading VAN MORRISON’S DRESSING ROOM — liberated for her by Bap, a friend also of that singer. “They told me he is an ardent Kerouac fan,” she tells me.

That ardour was felt by many rock stars — Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin — and Kerouac spoke of being contacted by John Lennon to explain that “beat” was part of his band’s name and concept. “He was sorry he hadn’t come to see me when they played Queens,” said Kerouac (referring to the Beatles’ first 1965 U.S. concert at Shea Stadium). “I told him it’s just as well, since my mother wouldn’t let them in without a haircut.” Nice story, Kerouac.

Bap recently asked Carolyn if she would do a background reading on a CD for his song “Moriarty’s Blues.” The passage is from her acclaimed 1990 memoir Off the Road: My Years with Cassady, Kerouac and Ginsberg. This was done at a studio also used by Van, she “taking photos every inch of the way” for her offspring — Cathy, Jami, John, all fans of the singer. She did the first chapter’s ending in one take, “a cool sax” at the end. Now here’s a souvenir of that fun, the sign, with a big red kiss planted on its plastic cover by “a crazy Irish girl friend.”

The passage is about Carolyn’s first meeting with Neal Cassady. Generally, I trust her version of things, and yet, asking where she first met Kerouac — a Denver bedsit she shared with Neal, On the Road indicates — I learn that she can’t remember.” How unreliable memory is about some things,” she concludes.

Scholars are even more removed from the past, and it’s shocking to leaf through biographies in her living-room bookcase and note her acid corrections. (In one, about Neal’s wish to put his “pretty body” on display: “Where do you get this stuff? These absolutes?”) Carolyn starts clanging something discovered on a shelf. “Ginsberg’s finger cymbals,” she says, laughing. “Where’s that prayer thing?” What a house: I wonder if one of Kerouac’s lumberjack shirts will show up somewhere.

She puts on a video of herself being interviewed at a Prague conference on the Beats. It makes us laugh, having been shot by someone with a mini-camera attached to his head. The thing slips partway through to give a skewed angle, so that abruptly she’s seen sideways and apparently down on the ground.

Yes, in Prague they love the Beats — and notably did so in Iron Curtain days when Ginsberg was crowned there as King of the May. Those in repressed or developing countries find in the Beats an example of liberation. Confabs about them are held as distantly as in China, where the young want to learn from them about mobility and choice.

Putting on Janet Foreman’s documentary The Beat Generation: An American Dream, Carolyn responds as if at a ball game between hometown heroes and bums. Con man Herbert Huncke talks about heroin, and she asks, “Who cares about these people, ugh!” But she admits that Kerouac “was so interested in how Huncke got that way” — an addict and a thief — as to present him as someone “not ready for the scrap heap.” We see the Beats at Columbia University, drawn to such underworld types.

Burroughs comes on, a Harvard grad older than the rest, whose avenue to ecstasy was through drugs. “Stupid” and “boring,” says Carolyn — who has tried drugs, and is tolerant by nature, but fears loss of control. So did Burroughs, actually, decrying control mechanisms whether narcotic or political.

Ginsberg appears, amusing Carolyn with talk of the term fiend used to demonize: “dope fiend” and so on. But when footage of him reading the “Moloch” section of Howl begins, she hits the mute, exclaiming, “That’s enough!” This gloomy part impresses many, she allows, but is too facile. “Everybody knows what’s wrong, for Christ’s sake. In all the media now is this negativity, and it’s not productive or life-enhancing. Go for something good that’s going on.”

We come to Kerouac with Steve Allen on prime-time television in 1959. “And right now we’ll look into Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and he’ll lay a little on you,” says Allen, tinkling a soft jazz tune on his white grand piano. The guest then flawlessly reads On the Road’s sublime concluding passage that ends: “I think of Dean Mor-i-ar-ty.”

My tears arouse Carolyn to ask sternly, “What are you doing?” I withhold reply amid an interplay of strong emotion. She disappears to find a late photo of Jack — alcoholism’s effects tragically evident — taken by a Long Island friend. “Doesn’t that say it all?” she murmurs. “I cried when I saw that.”

Farther on, someone is heard misdiagnosing Neal’s early demise. “No, he didn’t die of exposure!” Talking heads continue to arouse fury: “They’re so unenlightened! Taking themselves so seriously!”

A scene near the end provides the only footage I’ve yet seen of Cassady’s famed spontaneous rap. July 18, 1965, San Francisco’s City Lights Bookstore: “Ginsberg was being interviewed, Neal just happened to show up.” For that he received a third of the $250 Allen got for it.

Afterwards I replay the segment, fascinated by Neal’s body language. That quick but relaxed wave of a hand, as if to greet someone or swat a fly — I seem to recall such gestures made by characters known back in childhood. The same for the assuredness with which he leans back against a bookcase, hands planted against the sides of his head. Also a certain Charlie Chaplin rolling thrust of the torso. The way his eyebrows variously flick up and down, form an arch, give a sudden frown: broad mannerisms from long ago, vaudeville times.

The charisma now becomes more evident. As for the voice, I labour to write down what the man says, not comprehending but impressed by the jazzy rhythm of his delivery:

Neal: | Well, all the extremists, all the civil rights, all the kids, anybody in any extremes — |

Allen: | On both sides? |

Neal: | On every side, that’s right — we have a panoramic view of this thing, the earth’s going to tilt a little bit, natural catastrophes are happening everywhere, all the forms are dead — I mean you can handle — say you talk to a policeman, you know — I came in here yesterday and a gentleman took me around and I looked like I’m high so I just let people think I was high. Everything has forms, everything is known and everything’s changing and there’s no life in the forms. Life goes where the forms are, you see, and I’m going to have to — all this is hindsight that you’re talking about, it’s already too late, the Pentagon is taking care of it all, we’re doing this deliberately as far as that goes — |

This very linguistic flow transformed, by example, Kerouac’s writing. Few realize that his first novel, The Town and the City, chronicled a middle-class family’s life in a heavy literary manner. On the Road, a much rawer book showing life as wild, confused, outrageous, perverse, foolish, chaotic — the way it often turns out, that is — was written in the freer style of Cassady’s letters to him.

Eminent U.S. critics in 1998 placed this slightly fictionalized adventure tale fifty-fifth among the last century’s most important fictional works. It changed how people viewed the world, says Carolyn. “It’s wonderful how he celebrates all kinds of human beings, life in every form, the tiniest American place. Jack thought about things and saw individual lives — that’s really what turns everyone on.”

I’ve gained a belief that this love for immediacy, this delight, was shared by the other Beats. Ginsberg might have spoken for all when he said, “Life should be ecstasy.”

Afterwards I come upon a poignant still life of hers, Railroad Blues, detailing items linked with Neal’s job as a brakeman and conductor with Southern Pacific. Despite a rowdy car-stealing youth, he long strove for the respectability of owning a home and fulfilling parental duties — benefits coveted along with a life of the mind. The woman globally known as “Queen of the Beats” bore his children while continuing her artistic pursuits; one of her oils here portrays Jami in ballet costume: “All afternoon at her dance lessons, and I went to every practice.”

Here’s her 1952 photo of Neal and Jack hugging each other in front of the Cassadys’ San Francisco home, taken soon before Neal departed on a long railway shift with a suggestive remark about leaving the two alone. Irritated by this affront to monogamy, and more so by his clear-cut blessing on an affair, she initiated one — perhaps the best known of all Beat experiments. “I wasn’t in favour of sharing my affections with two men,” she tells me. “Neither of them knew how to arouse a woman, and Jack was apologetic. But I liked all the hugging, never had it as a child.” So much for those On the Road studs.

She asks whether I’d like to hear the audiotape this pair made in 1953. Hey, is the pope Catholic? “The master tape,” she explains, “it’s all I have since somebody nicked the copy.”

Carolyn gets the tape into the player backwards, then correctly, but believes that she has to rewind it. A wrong button is pressed and the BBC’s Saturday afternoon jazz program comes on. Now she would rather hear that. Also, by family parlance she notes that “the sun’s past the yardarm” — meaning our afternoon wine session is overdue.

Later she does manage to get the tape going, and laughs to hear her husband cry “Yeaaah” while Kerouac reads from his novel Dr. Sax: “Shows their mutual appreciation of each other, how Neal supports Jack.” Here’s Cassady reading some Proust, and Kerouac doing some scat singing. A dream departure back to 1953: “There’s some Miles Davis on this — Jack was by himself, his eyes were closed — it’s our song.”

The extended dialogue in Visions of Cody that Jack transcribed — where might be the tape for that? “We kept recording over the same tape to save money,” she explains. Little more than this treasure now remains, hanging by a thread.

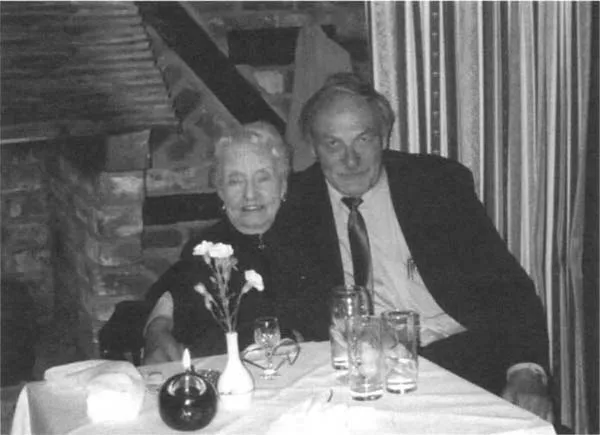

Carolyn Cassady dines out with me, happy to take a break from writing her autobiography, which is certain to become a classic about the Beat era and possibly the last by anyone who lived through it.

We have dinner at my hotel’s restaurant and then, waiting for the taxi, see a falling star. This leads us to talk about Cassady’s own flame-out, dying mysteriously in Mexico. His son, John, dug up a story that Neal, near the end, would have upon his shoulder a parrot, gifted at imitating his rap. We laugh over this, though regretful that no recording of the bird’s feat was made.

A two-year jail term for marijuana possession ended Cassady’s railway career, much disorienting him, and he and Carolyn divorced in 1963; neither of them ever remarried. Not conventionally religious, Carolyn never thought of the Beats’ unorthodox behaviour as sinful — which Jack and Neal did, being Catholic-trained — and never antagonized LuAnne Henderson, Neal’s first wife, who ever remained close to him.

Her tolerance of Neal’s pleasure-seeking is revealed by a new 490-page volume of Cassady’s correspondence, superbly edited by scholar Dave Moore. But in a January 1966 letter she asks that Neal no longer casually drop by, having shown John “that the life here that you rejected is for the birds — that any discipline, school work, self-improvement, efforts for the future, respect for rules, me or the law is asinine.” This is more like the woman I’ve gotten to know, firm of conviction, and John turned out to be a sunny individual loved by all.

Prominent in Neal’s final years was the strip-dancer Anne Murphy. Carolyn has a professional photo of this dazzler in costume with a long bare midriff and flashing smile, inscribed, “To Carolyn with love!” The world of showbiz.

“Highly sexed, so she didn’t need arousal,” she reflects. “Neal’s ‘healing sex,’ holy cow — Anne wrote about it beautifully.”

In childhood Carolyn spent hours copying Varga pin-up girls, “to the consternation of my mother, who saw them as sex symbols.” Burlesque shows don’t demean women, she feels: “What better way to use their ultimate God-designed physical form than to share it with lots of people, not just horny men as prostitutes?”

On the Road’s second page shows an avowal by Neal (“Dean Moriarty”) that “sex was the one and only holy and important thing in life.” Carolyn regards the body as “a marvellous instrument” (having drawn it since being “old enough to hold a pencil”) and the genitals as “our most spiritual connection with creation.” Yet it is the mind that matters, she argues, believing Burroughs and Ginsberg to be “stuck below the belt. So infantile.”

What positive benefits were in her marriage, beyond the excitement and children? “I learned from Neal,” she says, “that you don’t have to let anyone else tell you how to think and feel.”

On another visit, I ask whether the Beats might be comparable to England’s Romantic poets — the drug-addicted Burroughs as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Jack the self-documenting William Wordsworth, Allen as Percy Shelley (though also emulating William Blake), Neal as Lord Byron, Carolyn as that womanizer’s respectable wife — and all espousing “the language really used by men” as championed in Lyrical Ballads. Does that make sense?

I get an unqualified yes: “The Romantics were typical Beats, all rebels against convention and despised by the social order.” To be a writer, and “naughty,” made up the essentials. “Shelley offered Mary to his friend, and in San Francisco it was similar.” So there we have it.

The Beats looked to the future but also to the literary past. Man...