Harriet Tubman is one of the most well-known figures connected to slavery and the Underground Railroad. Her story is the continuation of one that had its beginnings much earlier, on the continent of Africa, the ancestral home of all black people.

Harriet Ross Tubman was one of the most famous conductors on the Underground Railroad. She was not content with being free after her escape from the Brodess plantation when so many others were still in bondage. She risked her life to make numerous trips into southern slave-holding states, to rescue family members and others. Her courage, strength, and dedication to fighting slavery led her to join the Union side during the American Civil War. Throughout the war, Tubman acted as a nurse, scout, and military strategist.

Harriet Ross Tubman was one of the youngest of the eleven children born to Benjamin (Ben) and Araminta (Rittia, “Rit”) Green Ross in Dorchester County of Maryland’s Eastern Shore around 1820. Harriet Ross (later Tubman) was born a slave since both of her parents were slaves; Rit was owned by Edward Brodess (also spelled Brodas or Broades) and Ben was owned by Dr. Thompson. The marriage of her parents’ enslavers brought Ben and Rit together on the same plantation. Harriet’s great grandparents belonged to the Ashanti tribe and were captured from Central Ghana in 1725. This made Harriet the fourth generation of her family to be enslaved in the United States.

When Harriet was very young, she was free to run about the plantation while her family went to work in the fields. Young enslaved children were cared for by slaves who were too old to do the more strenuous work. Each year the slaves were issued their clothes and Harriet received her rough cotton smock, but nothing else, just like the other slave children. No shoes were given to slaves, and Rit, like the other enslaved adults, received plain outfits or the used clothes of the master’s family and his staff. To keep warm on chilly evenings, Harriet would snuggle up to her mother as they, along with the rest of the family, tried to sleep on the dirt floor of the tiny place reserved for them as a home. At least Harriet had the benefit of warm, nurturing parents and the security of being in the same place as her family, as many children were sold away never to know what had happened to their parents or brothers and sisters. Something as simple as a birthday was not given any recognition, so slaves knew little of their African heritage, little of their family heritage, and little of their personal heritage.

From The Refugee by Benjamin Drew, Harriet Tubman said of her life:

I grew up like a neglected weed, ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it. Then I was not happy or contented: every time I saw a white man I was afraid of being carried away. I had two sisters carried away in a chain-gang — one of them left two children. We were always uneasy.

Now that I have been free, I know what a dreadful condition slavery is. I have seen hundreds of escaping slaves, but I never saw one who was willing to go back and be a slave. I have no opportunity to see my friends in my native land, if we could be as free there as we are here. I think slavery is the next thing to hell. If a person would send another person into bondage he would it appears to me, be bad enough to send him to hell if he could.

By the time Harriet was about five, it was decided that she should be hired out to other people. Brodess would charge for Harriet’s services and keep the money that Harriet earned. As was the custom for slaves, she took another name when she was hired out, calling herself Araminta or “Minty.” For this substitute owner, Harriet was to clean all day and rock the baby all night. Because she was a slave, not a “person,” her need for sleep was overlooked. Her mistress wanted to make sure she got her money’s worth out of her slave, even when the slave was scarcely older than the child she was expected to care for. She dusted and swept to the best of her ability, but because some dust remained in the room she was whipped about her face, neck, and back. This process was repeated four times until her mistress realized that Harriet needed to be shown how to do it correctly. Until the day she died, she bore the marks of these and subsequent beatings. Harriet detested indoor work; she detested slavery. In order to rock the baby, Harriet had to sit on the floor since the child was almost as big as she was. If the mistress was awakened by the cries of the child, Harriet was beaten. When Harriet was returned to her mother because she was ill, her mistress said that she had not been worth a penny.

On another task, Harriet was to learn to weave, but the fibres in the air bothered her — she did not do well. Then the master, James Cook, had Harriet tend his muskrat traps in the nearby Greenbriar swamp. Harriet preferred to be outdoors, away from the constant glare of the mistress, but she soon became sick and feverish due to the insects and dampness of the swamp. Her master demanded that she continue to work, but when Harriet was unable to she was returned to Rit to regain her strength. Slaves were not considered people or citizens of the land they toiled, so Rit’s knowledge of helpful herbs and her almost constant care got Harriet through her bout of measles and pneumonia — no doctors were summoned for “property.” Harriet later said that her owner, Brodess, was not unnecessarily cruel, but those to whom she was hired out to were “tyrannical and brutal.”

Harriet was deprived of many of the things that her owners took for granted. When she was hired out to a family near Cambridge to do housework, young Harriet was tempted to try one of the sugar cubes she saw in the sugar bowl. She noiselessly removed one cube and popped it into her mouth, but she was convinced her mistress had seen her stealing. Fearing punishment, she ran away, hiding in the pig sty. She hid for five days, eating the same food that the pigs ate. This was not too difficult to do since in certain respects it was better than what she was normally given to eat. Finally, she came out of hiding and was whipped for running away.

Harriet was described as a willful and moody child — perhaps she was trying to express her independence. She was adamant about having outdoor work, so Brodess relented. At least he would be able to get some more money from her outdoor work instead of having other owners sending her back all the time because she was a poor house worker. As such, nine-year-old Harriet was hired out to do field work. This was an area that Harriet did well in. She enjoyed the outdoors, the feeling of almost being free since she was not being closely monitored. Luckily for Harriet, because she proved valuable in harvesting, tilling, and planting, she was not used for breeding purposes. Harriet’s outdoor work also had the side benefit of strengthening her petite body and increasing her endurance, which would later serve her well on her treks north.

Being outdoors with other travelled slaves brought Harriet into contact with stories of escaping slavery, and she learned that freedom could be had by following the northerly flow of the Choptank River out of Maryland or by following the “drinking gourd,” which was the North Star. In this same way, she learned that the nature of enslavement in the deep south (Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina) was decidedly different, the work more taxing and ongoing, the conditions and punishments often even harsher.

When the sun comes back, and the first Quail calls,

Follow the drinking gourd, For the old man is a-waiting for to carry you to freedom

If you follow the drinking gourd.

Chorus:

Follow the drinking gourd,

Follow the drinking gourd,

For the old man is a-waiting for to carry you to freedom

If you follow the drinking gourd.

The riverbank will make a very good road,

The dead trees show you the way.

Left foot, peg foot traveling on,

Following the drinking gourd.

The river ends between two hills,

Follow the drinking gourd,

There’s another river on the other side,

Follow the drinking gourd.

When the great big river meets the little river,

Follow the drinking gourd.

For the old man is a-waiting for to carry you to freedom

If you follow the drinking gourd.

While Harriet’s owner may have been, in comparison to other slave owners, “fair,” he did treat his slaves harshly mainly because he developed financial problems. To raise money, he abruptly sold two of Harriet’s older sisters, Linah and Sophy. This act not only separated the sisters from Ben, Rit, and their other brothers and sisters, but also left two of Linah and Sophy’s children behind. This was the norm for slaves, but it made Harriet decide early on that she would try to take control of her life, that she would be free.

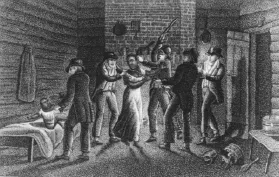

This woodcut shows a heartbreaking scene in which a mother in bondage is wrenched from her baby to be taken to the auction block and sold away. Harriet’s older sister Linah was taken away in this fashion, never to be heard from again.