![]()

Chapter 1

Beginnings

It all began more than 150 years ago in a small street within sight and sound of the docks of Greenock. It was there, in a close off Cross Shore Street – a narrow lane running down the quayside where lighters loaded their cargo, and steamboats from Glasgow disgorged their passengers – that William Quarrier was born on 29 September 1829.

Greenock, on Scotland’s Firth of Clyde, was in 1829 a busy industrial town with an illustrious shipbuilding history. Scott’s Shipbuilding and Engineering Company of Greenock, founded in 1711, was one of the many companies which helped to make Greenock the centre of shipbuilding on the Clyde during the eighteenth century. By the early nineteenth century new shipbuilding centres had developed further up the Clyde, notably at Port Glasgow and Dumbarton, but Greenock was still the chief highway to the Atlantic, and every day great ocean-going liners anchored out at the Tail o’ the Bank. Greenock could also claim fame as the birthplace of James Watt, inventor of the steam engine. And now, ten years after Watt’s death, another child destined for fame was born.

William Quarrier was the second of three children, and had an older and a younger sister. The family had little money and his mother often had to look after the household on her own for long periods while her husband plied his trade as a ship’s carpenter, calling at ports all over the world. It was while William’s father was working on a ship in Quebec that disaster struck: he contracted cholera and died, leaving his family destitute thousands of miles away across the sea. Annie Quarrier had three children to feed and clothe, and no source of income, so she had to try to provide by herself. She opened a small shop in Greenock but it was not successful and, after months of worry and despair, trying to make ends meet, she decided that she would have to move the family to Glasgow and find work there. She scraped together enough for the fares for one of the big steamers which ran daily between Greenock and Glasgow and, one afternoon in 1834, William Quarrier, just five years old, stood with his family on Glasgow’s busy Broomielaw quayside where all the big Clyde steamers docked.

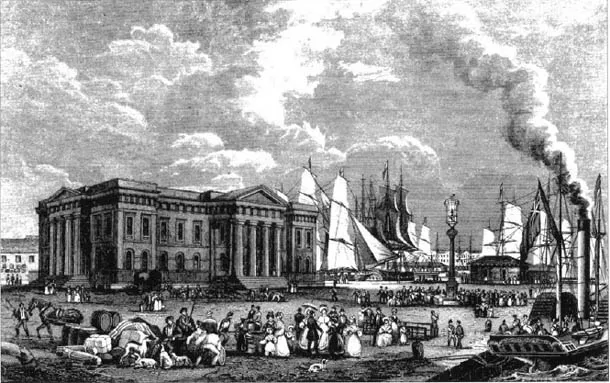

Customs House Quay, Greenock (reproduced by courtesy of Greenock Central Library)

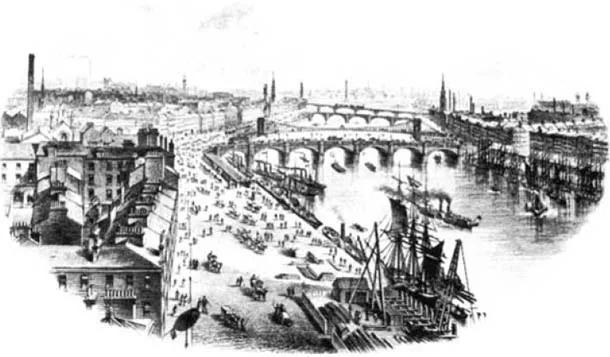

Broomielaw in Quarrier’s day (reproduced by courtesy of The Mitchell Library)

Early Victorian Glasgow was in the throes of industrial expansion. The city was superbly placed for trade with the world: down the Clyde lay the route to the Atlantic and commerce with the American continent; to the east, the Forth and Clyde Canal opened the way to the North Sea and Europe. All along the Broomielaw, great ships, heavy with cargo, lined the docks five or six deep, waiting to unload their goods and materials from all over the world – timber from South American forests, sugar and rum from the West Indies, fish and chemicals from Europe and Russia. Passenger and cargo steamboats nudged past one another on their way to Liverpool, Belfast and Dublin, and as they went bustling down the river they would meet vessels heading for Glasgow from local resorts all over the Firth, such as Millport on the Isle of Cumbrae and Rothesay on the Isle of Bute.

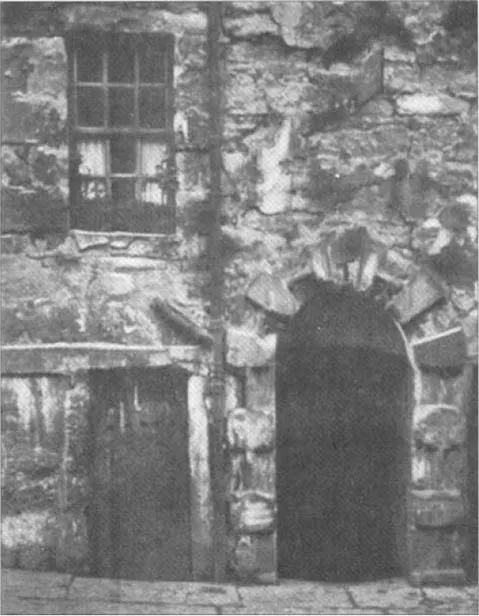

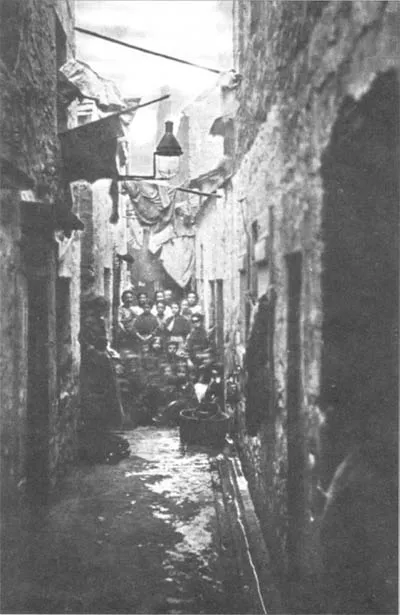

William Quarrier’s birthplace in Cross Shore Street, Greenock

The city’s famous Tobacco Lords, once to be seen strolling along the Trongate in their scarlet cloaks, were gone now and in their footsteps walked men whose money lay in Glasgow’s new booming industry – cotton: tons and tons of it, pouring into the city for delivery to Scotland’s 134 mills, almost all of them within twenty-five miles of Glasgow. The cotton and textiles industry spawned a host of factories all over the city, employing thousands of men, women and children. Dotted thickly on both sides of the river were spinning and weaving mills, lawn and cambric manufacturers, linen printers and dyers, sewed muslin makers, yarn merchants, chemical and dye works, steam-engine manufacturers. Glasgow also boasted other industries besides cotton; many people worked in the iron, brick and glass works and, in a little village called Govan on the south bank of the river, were the beginnings of marine engineering which was to be the cornerstone of the city’s industry from the 1860s onwards.

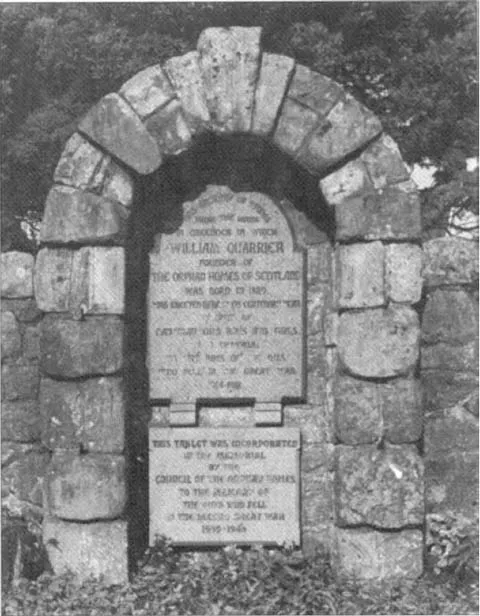

The stone archway to Quarrier’s birthplace in Cross Shore Street now forms the War Memorial just inside the main entrance to the Village

It was to this expanding, wealthy city that the Quarrier family came to make a new start. But, with very little money, they were forced to live in one of the poorest and most overcrowded areas of the city. Like thousands of others, they experienced the dark side of Glasgow’s industrial success and joined the ranks of the city’s growing population of poor, crowded in dark and dingy tenements amid factory and mill.

With the expansion of industry and the vast migration of people from rural areas to the city in search of jobs, among them a constant stream of Irish, Glasgow’s population had rocketed from 42,832 in 1780 to 110,460 in 1811 and more than 200,000 at the beginning of the 1830s. This caused severe overcrowding in certain parts of the city with which the authorities simply could not cope. At that time Glasgow was divided into four completely separate and independent burghs, and there was no one single authority responsible for clearing the overcrowded areas and building better houses. The worst spot was the rectangle of alleys and wynds formed by the Trongate to the north, the Saltmarket and Stockwell Street to the east and west, and the riverside to the south. Time and again since the early years of the century this area had been singled out as a black spot containing the worst elements of appalling housing, insanitary conditions and disease-ridden streets. One particularly strong critic was a Mr J.C. Symons, a government official who was sent to Glasgow in 1835 to inspect the living conditions of handloom weavers across the river in Paisley. Mr Symons was so appalled by some of the places he saw in the centre of Glasgow that he could not refrain from including in his report a vivid description of the horrors he encountered:

The Wynds of Glasgow comprise a fluctuating population of from 15,000 to 20,000 persons. This quarter consists of a labyrinth of lanes, out of which numberless entrances lead into small courts, each with a reeking dunghill in the centre. Revolting as was the outside appearance of these places, I was little prepared for the filth and destitution within. In some of these lodging-houses (visited at night) we found a whole lair of human beings littered along the floor, sometimes fifteen or twenty, some clothed and some naked, men, women and children, huddled promiscuously together. Their bed consisted of a layer of musty straw intermixed with rags. There was generally no furniture in these places.

It was in a close off the teeming High Street, on the edge of this most congested area of the city, that the Quarriers found a room. The High Street, notorious for the length and narrowness of its closes, was one of the four main streets which formed the ancient centre of Glasgow. The Saltmarket, the Trongate, High Street and the Gallowgate all converged at Glasgow Cross. These streets had been the business hub of eighteenth-century Glasgow, but by the time the Quarriers arrived the middle-classes had long ago migrated to the west of the city, leaving their once-elegant two- and three-storey apartments to house far more people than they were ever meant for.

In their High Street room Annie Quarrier tried to provide for the family by taking in fine sewing from one of the big warehouses. William helped her by carrying the finished bundles back to the warehouse and collecting more, but there was never enough work for his mother to make ends meet. So, at the age of seven, William was sent to work in a factory (probably the one owned by George Stewart, Pin Maker and Wire Drawer) in Graeme Street, near the Gallowgate. For ten or twelve hours a day, six days a week, he sat at a table and fixed the ornamental head tops on to pins – and all for the princely sum of one shilling a week. It was not in the least unusual for a child of his age to work those sorts of hours. Before the 1833 Factory Act to ‘Regulate the Labour of Children and Young Persons in Mills and Factories’, the normal working day for children from six years upwards in the cotton mills was anything between nine and twelve hours. Young boys and girls were employed as ‘scavengers’, crawling under the machines to pick up fluff and rubbish, or as ‘piecers’ whose job was to tie the threads together when they broke. Down in the coalmines, children spent long, damp, dark hours crouched beside the little doors which they had to open when the coal trolleys were sent along the line. In print works, lace factories and matchmaking factories young boys and girls worked alongside men and women, doing a full day’s work for small reward. For hundreds of families like the Quarriers, sending the children out to work was the only way of surviving.

A typical Glasgow close: No. 118 High Street (reproduced by courtesy of The Mitchell Library)

But even with William’s contribution to the family’s budget, the Quarriers were very, very poor. Years later he wrote of the hardships of these early days – in particular, he remembered one day when he stood in the High Street ‘barefooted, bareheaded, cold and hungry, having tasted no food for a day and a half’. Poverty like that was common on the streets of Glasgow and many were much worse off than the Quarriers. At least William’s family had his weekly shilling and whatever his mother earned, but for those with no source of income there was only parish relief. Since the sixteenth century, Scottish parishes had given small amounts of money to those who could prove that they were in need and unable to provide for themselves. The Kirk raised the money through voluntary collections, funeral dues and other such means, and this was then distributed among poor families in the parish. In Glasgow money was raised through compulsory assessment of the means of the wealthier members of the town and distributed under the auspices of the Town Hospital.

To be dependent upon poor relief in nineteenth-century Glasgow was to be among the lowest and most wretched in society. Paupers were looked down on by the hard-working respectable citizens, and the amount of money to which a person on poor relief was entitled was usually very little, enough only for a very spartan way of life – and sometimes not even for that; according to one Donald Ross, an agent of the Glasgow Association in Aid of the Poor, some paupers had to survive on appallingly little, barely enough for food and warmth. Ross compiled a document in 1847 entitled Pictures of Pauperism: The condition of the poor described by themselves in fifty genuine letters, addressed by paupers to the agent of the Glasgow Association in Aid of the Poor; in his indignant Preface to the letters, Ross cites the example of an old widow who lived in a tiny apartment. She was:

. . . without food, without proper clothing, without fuel, and without furniture. She was allowed five shillings per month by the parish, out of which she paid three shillings per month for rent, leaving two shillings a month, or little more than three farthings a day for food, fuel and clothing!

According to Ross, such low payments were by no means unusual.

Another feature of the workings of the Poor Law in Scotland was that, traditionally, poor relief could only be administered to those who were destitute and disabled; in other words, if a man were unemployed but able-bodied he was not officially entitled to parish aid. He might be given a little money in return for some sort of community work – breaking stones on the highway, for instance – or the Poor Inspector might tide him over with something for a day or two, but officially only widows, sick or infirm men, deserted wives, orphans, deserted children and the aged were eligible for relief. This meant great hardship during the periods of mass unemployment, such as the ‘Hungry Forties’, but it stemmed from a widespread attitude that unemployment was somehow the fault of the individual, and that a man without a job simply hadn’t looked hard enough for one.

Those not entitled to poor relief had to turn to one of the many charitable organisations and voluntary societies, such as the Glasgow Society for Benevolent Visitation of the Destitute Sick and Others in Extreme Poverty, a high-falutin’ title for a very practical society which issued tickets entitling the holder to food, clothing and other necessities at certain specified shops all over the city. The New Statistical Account for 1841 listed thirty-three ‘Benevolent and Charitable Institutions of Glasgow, exclusive of Widows’ Funds, Benefit Societies, Charity Schools and Maintenance of Paupers’, and new societies were being formed all the time to try to ease the hardships of poverty and want suffered by so many.

The High Street, Glasgow (reproduced by courtesy of The Mitchell Library)

The Quarriers bore their share of hunger and want as they eked out a living, day by day. But William’s mother realised that he needed a proper trade to secure his own and the family’s future, so when William was about eight years old she had him apprenticed to a shoemaker in the High Street. Most of his work consisted of running around after the men in the shop, lighting their pipes, fetching and carrying and preparing the rosined threads for sewing. This did not last for long, however; according to John Urquhart, Quarrier’s earliest biographer, the business went bankrupt through the intemperate drinking habits of the owner. So another situation was found for William with a shoemaker in Paisley, on the south side of the River Clyde. This meant he had to walk there and back every day – a distance of some thirteen miles. And the shoemaker’s apprentice didn’t even have a pair of shoes of his own! But William Quarrier was a determined little character and one cold, dark New Year’s Eve he even raced the stagecoach into the city on his way back from work. He doggedly chased it mile after mile, as the coach bumped through the gas-lit streets, and by the time it reached the ‘Half-Way House’ in Paisley Road West the passengers were so amazed and delighted by the tenacity of the skinny boy running behind that they started to throw him coins and cheer him on. They dragged William into the warm inn parlour and plied him with food and drink. Then, flushed with Hogmanay bonhomie and ‘Half-Way House’ beer, they ushered him into the coach and paid his fare the rest of the way to Glasgow.

It’s a story too irresistibly true to the character of the man to be the mere invention of a devoted biographer. That boy became the young man who, years later, joined Blackfriars Church in Glasgow and, appalled at the poor attendance, de...