![]()

Chapter One

Coming to Missouri

Missouri and Missourians on the Eve of Statehood

“This is probably the easiest unsettled country in the world to commence farming in.”

A traveler to the Missouri Territory in 1817

I GREW UP among and around farmers, people who never ceased to amaze me with their deep sense of hope and optimism. Their lives were uncertain and hard, and they lived with the knowledge that any number of occurrences could disrupt their well-being and postpone, if not shatter, their dreams. The farmers I knew in mid-twentieth-century Missouri worried over things they knew they could not control, especially the weather: droughts, hail, windstorms, and early frosts. They worried over their crops, how to find help to harvest them, and markets where they could sell them. They worried about diseases that could claim their plants, their animals, the lives of their loved ones, or even themselves. Despite their worries, however, they seemed to approach each new growing season with a sense of adventure and hope, a feeling that the coming year would bring prosperity and improvement in their lives.

It is not difficult to imagine that Henry Vest Bingham felt these same feelings of hope and promise when he ventured from Augusta County, Virginia, his birthplace, in the fall of 1818. He joined a group of fellow travelers on a westward trek in search of new land that he could call home. The son of a New England minister who had immigrated to Virginia, and a woman who was a Pennsylvania transplant to the same state, Bingham was looking for a new beginning, after having suffered a devastating financial setback in his birth county. As the editor of his 1818 diary noted years later, “He took the road west to begin again in search, preferably, of land that would raise the crops that were familiar to him—tobacco, corn, and hay.”

The group that Bingham travelled with was a scouting party in search of new land and new opportunity. He temporarily left behind his wife of a decade, Mary, and his children, including seven-year-old George Caleb, the future artist, and resolved to come back for the family when he found them a new home.

The trip west was arduous and challenging, even dangerous. The group followed a trail that by 1818 was already well-travelled, from Virginia, through Kentucky, across the southern part of Indiana, through Illinois, and into Missouri by way of St. Louis, a distance of more than seven hundred miles.

The group arrived in St. Louis on June 8, 1818. Bingham described the city as a town of “from five to Six thousand Inhabitants,” in which “The Indians Carry on a Considerable Trade . . . In furr & peltry.” The St. Louis economy was highly dependent upon the Indigenous people who lived in or made regular trips to the village, a reality not lost on one of the town patriarchs, Auguste Chouteau, who had a long-established reputation of trust among them. Other St. Louis residents held less benign feelings toward the Natives. In a late-life interview published in a St. Louis newspaper called The Republic, an elderly St. Louis-born French woman named Cecelia (Clement) Aubuchon recalled, “When I was a little girl [she was born in 1811] Indians used to come here and camp every year. . . . We were afraid of them. . . . I hated the Indians.”

After spending five days in St. Louis, Bingham’s party headed west to St. Charles. He described that town as being “Scatteringly Built and mostly in the old french Stile Exept some New houses Lately Erected By Americans,” adding, “It is at this time mostly Inhabited By Americans who have Commenced Improving the place Rappidly.” Bingham reported that St. Charles had about 1,200 Inhabitance” at the time of his visit.

By June 17, 1818, Bingham had seen enough to determine that he would most likely make Missouri his new home. He noted in his diary, “The Lands I have Seen in this Territory Being with other Advantages Sufficient Inducements to Cause me to move here In preference to any other Country I have yet Seen I am informed from Every Source that the Country farther up [in mid-Missouri] is Still more Rich and Desirable.” Bingham added, “If I do not Change my mind In favor of Some place that I may yet See Betwixt this and Augusta County Va. I Shall move my fammily to this Nighborhood Next Spring and more Effectually Explore the Territory.”

Bingham did not change his mind. He returned to Virginia, gathered up his family, and made plans to move. In the spring of 1819, he transported his wife, their seven children, his father-in-law and seven slaves to the newly bustling town of Franklin, Missouri, some 150 miles west of St. Louis. The Binghams set about becoming Missourians.

The Bingham emigration story, with slight modifications, played out thousands of times between 1815 and 1821, when Missouri formally joined the United States as the nation’s twenty-fourth state, and it continued to play out throughout the next generation of Missouri history.

The 1820 federal census of Missouri, taken even as the U.S. Congress debated whether and under what circumstances the territory should be admitted to the Union, revealed that 66,557 people lived within the territory’s borders in that year. Approximately fifteen percent (10,200) of that number were enslaved African Americans. Indeed, slaves had been present in the territory that would become the state of Missouri for at least a century prior to statehood, and the issues of slavery and race would be central to the Missouri experience for the next two hundred years and beyond.

Most of these people, Black and white, were Old Stock Americans, like the Binghams, who had come from east of the Mississippi River in the wake of the Louisiana Purchase (1803). Although migration into Missouri slowed somewhat during the War of 1812, the population increased to 25,845 by 1814. After the war, migration increased significantly, more than doubling the population of the Missouri Territory over the course of the next six years. To John Mason Peck, an itinerate missionary to frontier Missouri, “It seemed as though Kentucky and Tennessee were breaking up and moving to the ‘Far West.’ Caravan after caravan passed over the prairies of Illinois, crossing the ‘great river’ at St. Louis. . . .” The increase was aided greatly by a second series of bounty land warrants issued by the federal government for up to 320 acres each for volunteer soldiers who enlisted in the army after December 1814. This second series of warrants entitled veterans to land in either Arkansas, Illinois, or Missouri. Among the scores of veterans who acquired land in Missouri in return for their military service during the War of 1812 were Benjamin and Joseph Cooper, who obtained land in Howard County, and Joseph Moreau (or Morian), who earned land in Ste. Genevieve County.

“The bulk of the population” in 1820, according to historian Jonas Viles, “was to be found along the Mississippi [River] and in a great island along the Missouri in the central part of the state—the Booneslick country. . . .” Not surprisingly, the largest concentration of population was in the City of St. Louis, many of whose residents were descendants of the French founders who established the city in 1764 as a trade center for furriers. The city’s location on the Mississippi River, near the mouth of the Missouri River, made it an ideal location, as those two great rivers provided access to both the supplies of furs in the interior of the North American continent as well as markets for those furs and all manner of agricultural products the settlers hoped to sell at points throughout the vast river system and all the way down the Mississippi to its terminus at the international port of New Orleans.

St. Louis did indeed appear to be a city on the cusp of dramatic growth when the federal census was taken in 1820. The population stood at 4,598 that year, a gain of 228 percent over the course of the previous decade. Much of this phenomenal growth had occurred since 1815, at the conclusion of the War of 1812. In the wake of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, which formally ended the conflict, thousands of Americans crossed the Mississippi River into Missouri Territory in search of economic opportunity in the vast river valley and beyond.

The physical boundaries of St. Louis expanded during this period, and new houses were built at an unprecedented rate. The Missouri Gazette, Missouri’s earliest newspaper, reported that more than one hundred new houses were built in St. Louis in 1818 alone. Between 1815 and 1821, a total of 306 new houses were constructed in the city, roughly half of them substantial structures of either brick or stone.

During this same period, St. Louis’s economy was transitioning from one based on barter to money-based, with common laborers regularly earning $1.50 per day. At the same time, the city’s economy was becoming increasingly diversified. John Paxton’s 1821 St. Louis Directory identified forty-six mercantile houses, “carrying on an extensive trade with the most distant parts of the republic, in merchandise, produce, furs and peltry.” Artisans in the city included silversmiths, jewelers, bricklayers, stone cutters, carpenters, blacksmiths, gunsmiths, cabinetmakers, and tailors. Virtually any service or commodity that one expected to be able to purchase in an older, more established city in the eastern United States could be purchased in St. Louis on the eve of Missouri statehood. That said, St. Louis in 1820 bore little resemblance to a modern-day American city. Indeed, writing in 1971, distinguished Missouri historian Lewis E. Atherton opined that “In many ways the business structure of Missouri towns [including St. Louis] in 1821 more nearly resembled that of medieval European cities than of twentieth-century America.” As Atherton has written, “As owners of their own shops and tools and supervisors of all operations, master artisans were capitalists, managers, employers and workmen all in one.” Both artisans and laborers were in great demand, with virtually everyone who belonged to the latter class aspiring to become a member of the former.

A major source of commercial activity in St. Louis in 1820 remained the fur trade. The 1821 St. Louis Directory credited it with nearly one-third of St. Louis’s annual commerce ($300,000 of $1 million trade). There were two major fur-trading companies in St. Louis at the time: the one operated by the Chouteau family, who traded primarily with the Osages, the other the Missouri Fur Company of Manuel Lisa, who died in 1820, a few weeks short of his forty-eighth birthday. Both operations counted on the abilities of trappers and traders to work closely with Native American groups living along the Upper Missouri River.

St. Louis’s connection to distant markets, facilitated by its location on the Mississippi River and its access to the Missouri River, was greatly enhanced by the introduction of steamboats. The first steamboat to arrive in St. Louis was the Zebulon M. Pike, named for the American explorer who died in 1813, which docked on the city’s waterfront for the first time on August 2, 1817. By 1820, steamboats came into St. Louis with great frequency, and steamboat traffic on the Missouri River had become commonplace. This new means of transportation of both people and trade goods, in turn, connected St. Louis and Missouri River towns to eastern markets and helped to hasten the transition of the Missouri economy.

One can glean some insight into life in St. Louis on the eve of statehood from the recollections of a contemporary resident, David Holmes Conrad, who first visited the city on a cold, subzero-degree day on December 29, 1819. Conrad, then just a few days shy of his twentieth birthday, had travelled overland by horseback with a companion, cabinetmaker Joshua Newbrough, who had purchased 160 acres of land in the Boonslick a few months earlier. The duo travelled from Winchester, Virginia. The son of a prominent Winchester attorney who died in 1806, Conrad had recently completed his private training in the law and headed west to practice his new profession in the Missouri Territory. He obtained a law license in Missouri in February 1820.

According to Conrad, when he arrived in St. Louis, the “city” boasted a population of “not quite 5000” mostly French residents, with French being the dominant spoken language. “There were some Spanish residents as well, and a number of ‘Americans,’” primarily, according to Conrad, unmarried men, suggesting that these were young men who had arrived in St. Louis relatively recently and who, like Conrad, hoped for a new start in a promising new land.

The city, or “town,” as Conrad referred to it, struck him as “foreign,” unlike the towns he had seen in Ohio and Indiana along the way. Most of the houses in St. Louis were made of logs, arranged vertically in the French style of building, unlike the horizontal log structures with which he was more familiar. The “old proprietors and founders of the town” lived in mansions built on large lots—Conrad specifically mentioned the homes of town patriarchs Auguste and Pierre Chouteau, and also that of William Clark, governor of the Missouri Territory.

Native peoples continued to have a presence in St. Louis when Conrad arrived there. Indeed, he attended a “council with some Indian tribes,” hosted by Clark at the governor’s invitation. Although the French influence remained strong in St. Louis, Conrad was struck by the fact that “the most prominent officers of the territory were Virginians,” including Governor Clark, Lieutenant Governor Frederick Bates, and U.S. Surveyor of Public Lands, William Rector. “The Southern influence,” Conrad concluded correctly, “was largely and decidedly predominant,” and it informed and influenced St. Louis and much of Missouri for decades, especially in their reliance on the institution of slavery and their commitment to the notion of white supremacy.

Conrad was an unabashed Missouri booster. “The fertility of Missouri lands,” he wrote in his memoir, “can hardly be understood by persons who have not lived there.” Likewise, he observed, “The mineral resources of the country . . . are magnificent,” especially its iron, lead and coal supplies. Wild fruits and nuts were available in abundance and wild game “abundant to a degree almost incredible.” In short, Conrad concluded, “I never saw a country where the spontaneous product of the necessaries of life did so abound.”

The prevalence of French culture in St. Louis led to the presence of what Conrad described as “some strange old customs.” One was the chivaree, described by him as “a mock or masquerade ceremony of greeting to a newly married couple,” especially “when there was something disproportionate in the union,” such as a large age difference between the partners to the marriage. Crowds of revelers making lots of noise would gather at the newlyweds’ house and create “a racket,” “[t]he object [of which] was to enforce from the newly married pair a present for some public purpose, the church or the poor.”

The French chivaree tradition remained alive in Missouri, and even extended to the isolated and homogenous German Osage County community of my childhood more than a century later. I recall fondly a chivaree held in 1957, soon after local resident Leonard Burchard, a lifelong bachelor, age 59, married a young woman more than two decades his junior. The horn-honking, pot-banging, tin can clattering revelry involved left a life-long impression on an eight-year-old boy.

There were boosters aplenty in Missouri during the late territorial period, all of them encouraging potential immigrants to come to the state, to uproot themselves and move west of the Mississippi River. One of the earliest and most vociferous of these was the St. Louis newspaper publisher, Joseph Charless. A native of Ireland who immigrated to the United States in 1795, Charless worked his way from Pennsylvania to Kentucky and then to St. Louis, arriving in 1808. He became Missouri’s first printer soon after his arrival in St. Louis, and on July 12, 1808, he produced the first issue of the Missouri Gazette, the territory’s first newspaper. Over the course of the next dozen years, and especially after the end of the War of 1812, Charless used the pages of his newspaper to promote Missouri as a paradise for newcomers, especially farmers. He advertised the high prices that could be obtained for growing wheat in Missouri, but also proclaimed Missouri’s fertile soil and suitable climate as conducive to growing cotton, tobacco, grains other than wheat, and fruit. Additionally, Charless advertised Missouri’s mineral wealth, including its rich deposits of coal, lead, salt, flint, and other minerals. He also promised jobs aplenty for would-be laborers who did not want to farm or mine. There was a need in Missouri, he wrote, for blacksmiths, gunsmiths, wagon makers, brick makers and stonecutters, carpenters, and many, many other trades.

By 1820, the influence of French control over St. Louis could still be felt in local architecture, food, customs, and even language, although by this time the French men and women were already far outnumbered by their old-stock American counterparts. The latter group, most of them Upland Southerners, had, as mentioned, begun to trickle into the Missouri Territory after the region was acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase (1803). The trickle became a flood after the War of 1812 ended in the defeat of the British and the firm establishment of American control over the territory.

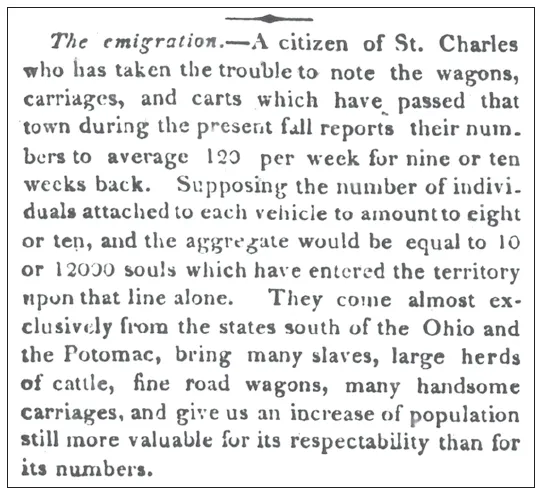

Fig. 6: This article, describing the large number of immigrants to Missouri passing through St. Charles, appeared in the St. Louis Enquirer, November 10, 1819. Credit: State Historical Society of Missouri.

Among the Americans who lived in St. Louis on the eve of statehood were a relatively large number of African Americans, nearly seven hundred persons, most of them enslaved. They served primarily as maids and body servants to the wealthy merchants who called St. Louis home. As historian Kristen Epps has written, “The Chouteaus [and other wealthy, well established St. Louis families] relied on bondspeople not only for their business enterprises, but also for subsistence agriculture and personal comfort.” Slavery was seen as the solution to the labor shortage in St. Louis and the rest of Missouri leading up to the period of statehood and beyond. It was also viewed as the key to the social, political, and economic control of African Americans, the subjugation and exploitation of whom were essential to the growth and maturation of the region.

...