eBook - ePub

Modern Economics

An Introduction

Jack Harvey, Ernie Jowsey

This is a test

Share book

- 584 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Modern Economics

An Introduction

Jack Harvey, Ernie Jowsey

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Jack Harvey's Modern Economics is a classic in the world of economics teaching and learning and is an ideal entry to the subject for introductory students in business and economics. This edition has been thoroughly revised and updated to reflect developments in a number of important and emerging areas of economics.

Also available is a companion website with extra features to accompany the text, please take a look by clicking below -

http://www.palgrave.com/economics/harvey/

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Modern Economics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Modern Economics by Jack Harvey, Ernie Jowsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART

VII

THE GOVERNMENT AND STABILISATION POLICY

CHAPTER | MEASURING THE LEVEL OF ACTIVITY: NATIONAL INCOME CALCULATIONS |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter you should be able to:

•show how the national income can be calculated in different ways;

•describe the difficulties of calculating national income;

•show the steps necessary to adjust from one measure of national income to another;

•describe the uses of national income statistics;

•explain the factors determining a country’s standard of living.

28.1THE PRINCIPLE OF NATIONAL INCOME CALCULATIONS

Fluctuations in the level of activity are monitored by quantitative information on the national income. Although the collection of statistics proceeds continuously, the principal figures are published annually in The United Kingdom National Accounts (The Blue Book). See www.statistics.gov.uk.

The principle of calculating national income is as follows. Income is a flow of goods and services over time: if our income rises, we can enjoy more goods and services. But for goods to be enjoyed they must first be produced. A nation’s income over a period, then, is basically the same as its output over a period. Thus, as a first approach, we can say that national income is the total money value of all goods and services produced by a country during the year. The question is how we can measure this money value.

We can tackle the problem by studying the different ways in which we can arrive at the value of a table.

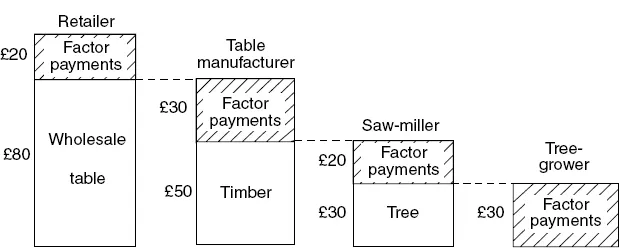

Figure 28.1 shows that the value of the table can be obtained by taking the value of the final product (£100) or by totalling the value added by each firm in the different stages of production. The output of the tree-grower is what he receives for the tree (£30) which, we will assume, cost £20 in wages to produce, leaving £10 profit. The output of the sawmiller is what he receives for the timber (£50) less what he paid for the tree. Again, this output (£20) is made up of wages and profit. And so on. The total of these added values equals the value of the final table. Thus we could obtain the value of the table by adding the net outputs of the tree-grower (forestry), the sawmiller and the table-maker (manufacturing) and the retailer (distribution).

Figure 28.1The value of the total product equals the sum of the values added by each firm

Alternatively, instead of putting these individual outputs in industry categories, we could have added them according to the type of factor payment – wages, salaries, rent or profit. This gives us the income method of measuring output.

Thus, if we assume (i) no government taxation or spending and (ii) no economic connections with the outside world, we can obtain the national income either by totalling the value of final output during the year (i.e. the total of the value added to the goods and services by each firm) or by totalling the various factor payments during the year – wages, rent and profit.

There is, however, a third method of calculating the national income. The value of the table in Figure 28.1 is what was spent on it. If the table had sold for only £90, that would have been the value of the final output, with the final factor payment – profit to the retailer – reduced to £10. Thus we can obtain the national income by totalling expenditure on final products over the year.

It must be emphasised that the money values of output, income and expenditure are identical by definition. They simply measure the national income in different ways. This was shown by the fact that factor payments were automatically reduced by £10 when the table sold for £90 instead of £100.

Before we proceed to examine in more detail the actual process of measuring these three identities, it is convenient if we first consider some of the inherent difficulties.

28.2 NATIONAL INCOME CALCULATIONS IN PRACTICE

General difficulties

Complications arise through:

1. Arbitrary definitions

(1)Production

In calculating the national income, only those goods and services which are paid for are normally included. Because calculations have to be made in money terms, the inclusion of other goods and services would involve imputing a value to them. But where would you draw the line? If you give a value to jobs which a person does for himself – growing vegetables in the garden or cleaning the car – then why not include shaving himself, driving to work, and so on? On the other hand, excluding such jobs distorts national-income figures, for, as an economy becomes more dependent on exchanges, the income figure increases although there has been no addition to real output (see p. 353)!

An imputed money value is included for certain payments in kind which are recognised as a regular part of a person’s income earnings, e.g. cars provided by a company to directors and employees.

(2)The value of the services rendered by consumer durable goods

A TV set, dishwasher, car, etc., render services for many years. But where would we stop if we imputed a value to such services? A toothbrush, pots and pans, for example, all render services over their lives. All consumer durable goods are therefore included at their price when bought, subsequent services being ignored.

The one exception is owner-occupied houses. These are given a notional rent to keep them in line with property owned for letting, whose rents are included, either directly or as profits of property companies. This also prevents national income falling as more people become owner–occupiers!

(3)Government services

Education and health services, although provided by the State, are no different from similar services for which some persons pay. Consequently, they are included in national income at cost. But what of certain other government services? A policeman, for instance, when helping children to cross the road is providing a consumer service. But at night his chief task may be guarding banks and factories, and in doing so he is really furthering the productive process. To avoid double-counting, this part ought to be excluded from output calculations. In practice, however, it would be impossible to differentiate between the two activities, and so all the policeman’s services – indeed all government services (including defence) – are included at cost in calculating national output (see p. 353).

2.Inadequate information

The sources from which data are obtained were not specifically designed for national-income calculations. For instance, the Census of Production and the Census of Distribution are only taken at approximately five-year intervals. As a result many figures are estimates based on samples.

Information, too, may be incomplete. Thus not only do income tax returns fail to cover the small-income groups, but they err on the side of understatement.

But it is ‘depreciation’ which presents the major problem, for what firms show in their profit and loss accounts is affected by tax regulations. Since there is no accurate assessment of real depreciation, it is now usual to refer to gross national product (GNP) rather than to national income (see Figure 28.3).

3.The danger of double-counting

Care must be taken to exclude transfer incomes when adding up national income (see p. 348), the contribution to production of intermediary firms when calculating national output (see Table 28.1) and indirect taxes when measuring national expenditure (see p. 350).

A fourth way in which a form of double-counting can occur is through ‘stock appreciation’. Inflation increases the value of stocks, but although this adds to firms’ profits it represents no increase in real income. Such gains must therefore be deducted from the income figure.

4. Relationship with other countries

(1)Trade

British people spend on foreign goods, while foreigners buy British goods. In calculating national expenditure, therefore, we have to deduct the value of goods and services imported (since they have not been produced by Britain) and add the value of goods and services exported (...