eBook - ePub

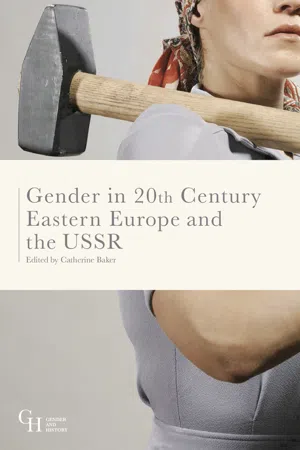

Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR

Catherine Baker

This is a test

- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR

Catherine Baker

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A concise and accessible introduction to the gender histories of eastern Europe and the Soviet Union in the 20th century. These essays juxtapose established topics in gender history such as motherhood, masculinities, work and activism with newer areas, such as the history of imprisonment and the transnational history of sexuality. By collecting these essays in a single volume, Catherine Baker encourages historians to look at gender history across borders and time periods, emphasising that evidence and debates from Eastern Europe can inform broader approaches to contemporary gender history.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR by Catherine Baker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia rusa. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Between the Fin-de-Siècle and the Interwar Period

1

Czech Motherhood and Fin-de-Siècle Visual Culture

Cynthia Paces

European women at the fin de siècle, or the turn from the 19th to the 20th century, were receiving unprecedented public attention on their personal and professional lives. As states took an increasing interest in their entire population’s health, women became recognized as crucial actors in maintaining and even improving future generations. While Europeans debated the concepts of nation, citizenship and rights, women demanded recognition as full members of their societies. Professional women in fields from medicine to journalism endorsed the popular European maternalist feminist philosophy that championed political and educational rights within a framework of social motherhood. Expanded opportunities for women, they argued, would benefit the entire society. Educated mothers raised intelligent citizens, and unmarried professional women could use their feminine traits to better society as a whole.

In this era, changes in Czech women’s lives could not be separated from the nationalist politics dominating Bohemia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Like other national minorities in multinational empires (including parts of the Ottoman and British Empires),1 Czech feminists situated their quest for rights within the needs of their nation, arguing that women served the nation by creating and protecting future generations and by imparting the Czech language and culture to them. Nationalist leaders and artists embraced and reproduced this powerful image of Czech womanhood in public art and in discourses about beauty and health. This chapter argues that these maternal symbols demonstrated women’s essential roles in nation building and public health while delineating strict and specific expectations for women. At a historical moment when gender roles were being negotiated and redefined, the mother stood at the centre of national iconography, as she would do in many other gender regimes throughout the 20th century.

Czech national iconography in this period contained two seemingly disparate female characters – the selfless, nurturing Czech National Mother and the educated, cosmopolitan New Woman. However, they were not mutually exclusive. The mother–child dyad became a frequent image on national monuments and murals, medical drawings, mothering guidebooks and public health posters, thus connecting women’s responsibility to the nation to the overall physical health of the national community. Yet the maternal symbol did not merely represent traditional values: it also reflected very contemporary struggles over the present and future of Czech nationhood. Maternal nurturing – often depicted through representations of breastfeeding – symbolized the preservation and progress of the Czech nation despite centuries of Austrian domination in Bohemia. Conversely, irresponsible maternal subjects suggested that some women failed to protect the nation’s health and secure its future.

By examining Czech visual culture, this chapter elucidates the pervasive maternal symbol’s multiple and contradictory meanings. Maternal images, ranging from sentimental to medical in tone, not only reinforced family hygiene guidelines but also opened discussions about female progress. Several major themes converged upon this maternal image: the centrality of the nation in Bohemian social discourse; the growing importance of public health, medicine, and science; and the role of social class in gendered expectations. The dynamic of reimagining mothers’ role and behaviour within specific understandings of modernity and nationhood would characterize struggles over reproductive politics and the gender order in many other political contexts during the century.

It is no surprise that mothers were common symbols in this era of rapid industrialization and urbanization. As feminist movements blossomed in Europe and North America, women and men questioned how social change would impact family life. The historian Joan Scott has demonstrated that when societies depict gender they must rely on ‘culturally available symbols that evoke multiple (and often contradictory) representations’, and similarly the art historian Rosemary Betterton has argued that artistic representations of mothers are sites where biological and social discourses meet.2 Czech representations of motherhood showed this in action. The nurturing mother represented values including patriotism, social progress, moral rectitude, aesthetic beauty and health, while an unfit mother provoked society’s greatest fears: illness, death and insecurity.

Maternalism’s principal message demonstrated women’s contribution to the national movement. As the historian Beth Baron has demonstrated, female symbols abounded in fin-de-siècle Europe and its colonies:

Through the use of the metaphor of the nation as a family, popular notions about family honour and female sexual purity were elevated to a national ideal […] [Mothers] were used as subjects and symbols around which to rally male support.3

While maternalist feminism was a popular form of women’s activism throughout Europe and North America, focusing on the Czech case elucidates important aspects of East European History and Gender Studies. In particular, the feeling of statelessness among many east European groups in an era of heightened national allegiances meant that discussions about gender were necessarily filtered through the language of national identity.

The Czech women’s movement coincided with increasingly divisive regional politics in the years leading to World War I. Bohemia had been incorporated into the Habsburg hereditary lands in 1526, and the Austrian Empire’s increasing centralization over the next three centuries destroyed the autonomy of the Czech estates. The predominantly Protestant Czech nobility was exiled during the Counter-Reformation, and German became the lingua franca. The 19th-century national revival, inspired by the French Revolution and European romanticism, resurrected Czech language and culture. Women such as Božena Němcová and Eliška Krásnohorská contributed by collecting rural folk stories and creating librettos for Czech-language operas.

After the 1848 failed uprisings and the 1867 division of the Empire between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Austrian Empire, Czechs felt even more insecure in their role as a small nation within a multinational Empire. Prague was nonetheless rapidly transforming from a German-dominated to a Czech city, whose municipal government, economy and culture increasingly reflected the shifting demographic. In this era Czechs founded voluntary organizations, political parties and educational institutions that instilled patriotism into Bohemia’s Slavic majority and challenged the region’s German cultural domination. An influx of Czech-speaking peasants changed Prague’s predominant language, and by 1880 Czech speakers had successfully overtaken the Prague city government. In 1897 Czechs won the right to use their language in the Austrian civil service, displacing German speakers in many key positions. With linguistic rights at the heart of the nationalist movements, women’s maternal roles had deep political resonance.

German and Czech Bohemians established separate cultural institutions and organizations, in effect creating parallel civil societies in Bohemia. Both Bohemian German and Czech national organizations asserted that their mother tongue, ‘the most holiest legacy of our ancestors’, was endangered and must be safeguarded.4 As children became pawns within competing national movements, both Czech- and German-speaking Bohemians linked parental love to patriotic education. The historian Tara Zahra quoted a 1909 brochure aimed at Czech parents proclaiming, ‘If you really love your children, allow them to be educated only in their mother tongue!’.5 As in many European languages, the Czech terms for family, birth and nation (rodina, porod, národ) shared a common root. Consequently, as women demonstrated their value to the nuclear family, they also proved their indispensability to the nation.

Another complexity of the fin-de-siècle maternal image was its links to public health and the dynamics of social class. Europeans were heavily invested in increasing and protecting their populations, and breakthroughs in germ theory and sanitation gave them new tools for their efforts. Michel Foucault named the ‘hysterization of women’ as a hallmark of the Victorian era. In Bohemia, as elsewhere, female bodies were analysed and medicalized, and women (in Foucault’s words) owed a ‘responsibility […] to the health of their children […] and the safeguarding of society’.6 In the heightened anxiety over which national group was to dominate Bohemia, this medicalized view of motherhood became crucial to concerns about the birth rate and population health. The symbolic mother transmitted gender norms and expectations for real women’s behaviours. The era’s visual and written texts encouraged women to connect biological functions to national and social duties. Through hygiene, clothing, exercise and comportment, mothers could display themselves as living embodiments of idealized artistic representations. However, these expectations were unrealistic for working-class women, who endured crowded living conditions, low wages and limited leisure time. Nonetheless, the idealized maternal depictions normalized bourgeois women’s behaviours and became iconic, tacitly warning women of the consequences to the nation and the family if their duties were not fulfilled.

However, Bohemian women did not merely succumb to the symbolic forms of power created through nationalized and medicalized representations. Maternalism also offered women an entry point into public political discourse. The historian Ann Taylor Allen has argued that we need to complicate our understanding of European feminism’s relationship to motherhood given that maternalist feminists created new forms of feminine power in both domestic and public realms.7 Czechs and other minority nationalist movements within the Empire, such as Poles and Hungarians, often supported women’s emancipation to distinguish their movements’ progressive ideals from the conservative Habsburg Monarchy. Further, in this era, the New Woman was becoming a powerful European icon, signifying society’s modernity and progress. This New Woman might be well educated, have a career, play sports, socialize in public or even run for political office. Czech women founded the Empire’s first girls’ gymnasium in 1890 without support or funding from Vienna.8 In 1902 a Czech woman became the first Austrian woman of any nationality to earn a medical degree ‘based exclusively on study in an Austrian University: the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague’.9

These modern accomplishments did not necessarily exclude the New Woman from motherhood. However, the power gained in this realm was predominantly for middle-class women, whose lifestyles were thought conducive to a healthy society. Poorer women were less able to achieve the strict rules on hygiene and childcare, and thus appeared not to fulfil their maternal duties. Further, they were less likely to bene...

Table of contents

Citation styles for Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR

APA 6 Citation

Baker, C. (2016). Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR (1st ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2998045/gender-in-twentiethcentury-eastern-europe-and-the-ussr-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

Baker, Catherine. (2016) 2016. Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR. 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://www.perlego.com/book/2998045/gender-in-twentiethcentury-eastern-europe-and-the-ussr-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Baker, C. (2016) Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR. 1st edn. Bloomsbury Publishing. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2998045/gender-in-twentiethcentury-eastern-europe-and-the-ussr-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Baker, Catherine. Gender in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe and the USSR. 1st ed. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.