- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

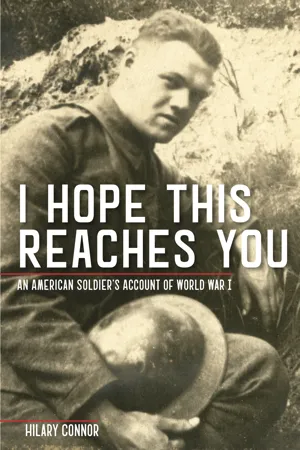

A medic's account of life during World War I.

I Hope This Reaches You: An American Soldier's Account of World War I begins in May 1917 with Byron Fiske Field (1897–1968) boarding a morning train bound for Detroit with one objective in mind: to help the United States win the war against Germany. A pacifist at heart, Field had just finished his freshman year at Albion College where he was studying to be a Methodist missionary. Although he found the idea of killing another human to be at odds with his Christian beliefs, like other Americans he was convinced of the righteousness of World War I—the war to end all wars—and he was determined to do his part.

In recounting Field's story, Hilary Connor relied on four principal sources of information found in a footlocker issued to Field as a member of the 168th Ambulance Company in the 42nd Division—or as it was more famously known, the Rainbow Division. The first of these sources is a handwritten diary kept by Byron from February 1918 to July 1919. The second cache of firsthand information is contained in two books that were co-authored by Field and other select Company members in the late winter and early spring of 1919, recounting events and personal experiences of the war— The History of Ambulance Company 168 and Iodine and Gasoline. The third and perhaps most extraordinary source is a collection of over three hundred letters written by Field during the war to his parents and college girlfriend. Included in many of the letters are mementos ranging from the petals of regional flowers in bloom to Red Cross notices to church service programs and other pieces of everyday life that proved invaluable in helping to create a broader and richer historical context. The last category of material is a voluminous collection of personal papers, including academic articles, speech notes, and opinion pieces, written by Field in the decades following the war. The breadth of materials is only further enhanced by the benefit of one hundred years hindsight, lending itself to a more thorough understanding of many of the momentous events that occurred during those years.

I Hope This Reaches You is a tapestry of human experience woven from the narrative threads of love, loss, loyalty, sacrifice, triumph, and tragedy that will call to any reader of historical memoirs.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

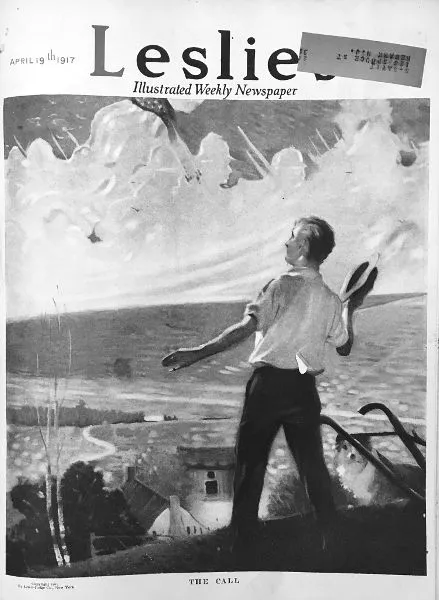

Answering the Call

We were at play—or work—at study. The days were filled with hours in the classroom, the chambers, and along the river in canoes. Spring suns had barely melted the last snows into the grass. Already we were thinking of the summer days when vacation would be with us, and we wouldn’t have to go a-hurrying to “eight o’clocks,” or give answer for too frequent cuts from classes.Oh yes, we read the newspapers, in the same detached way that any college boy scans the news for information about what is doing in the outside world. Our chief source of outside information however was the letter from home, and that was confined chiefly to remarks about the health and financial condition of our own family.We did read of the war—off there in Europe. Yes, we even heard occasional reference made to it in our class in European History, although the professor was more concerned in our knowledge of the significance of the Battle of Tours or Poitiers than Verdun or the Somme. The latter was too recent to be of immediate historical significance to him—it hadn’t been seasoned in foolscap and leather binding yet.We read of “atrocities,” of White Papers and Red Papers, of the Russian revolt, of Gallipoli—but for the most part they were “outside our world.” Spring was coming, and the annual class games, the walks which had been deprived us through the fields and woods, alone, or with our damozels.Then came April 6—and war. Still remote. As a high school boy, I had watched the Princess Pats being recruited in 1914. They had seemed just like any other “soldiers”—they were going over to Europe to get into a war about something or other. Some acquaintances had been filled with a spirit of adventure, or, thinking deeply, of a desire to do the right thing, as they saw it, and had gone over to Windsor, opposite Detroit, and joined up with the Canucks.But here we were in it. Newspaper reading took on a new significance. “Platitudinous” remarks of President Wilson were now accepted as too coldly matter-of-fact. We were pledged to support a Cause—“to help make the world safe for democracy.” We were involved directly, it seemed, because we refused to be dictated about when and where ships flying our flags could go—sort of a War of 1812 attitude. We were on the side of Right too—there could be no doubt about it—the other side had committed atrocities, had violated international law, had tried to take advantage of certain innocent peoples. We were a kind of eleventh hour “defenders of the faith.”

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- A Note on the Text

- 1. Answering the Call

- 2. The World’s Greatest Advertising Adventure

- 3. Marking Time

- 4. Passing Muster

- 5. This Is No Sunday School

- 6. Over There

- 7. Culture Shock

- 8. The Handwriting on the Wall

- 9. The Valley Forge Hike

- 10. Remember Jesus Christ

- 11. Baptism by Fire

- 12. There Must Be a Kind God Above

- 13. A Scene That Would Shock the World for All Eternity

- 14. The River of Blood

- 15. The Devil’s Business

- 16. The First All-American Affair

- 17. Death Valley

- 18. Enough to Narrow One’s Mind Forever

- 19. The Dawn of Peace

- Epilogue: The Journey Home

- Notes

- Bibliography