Three Tweets to Midnight

Effects of the Global Information Ecosystem on the Risk of Nuclear Conflict

Herbert S. Lin, Benjamin Loehrke, Harold A. Trinkunas, Herbert S. Lin, Benjamin Loehrke, Harold A. Trinkunas

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Three Tweets to Midnight

Effects of the Global Information Ecosystem on the Risk of Nuclear Conflict

Herbert S. Lin, Benjamin Loehrke, Harold A. Trinkunas, Herbert S. Lin, Benjamin Loehrke, Harold A. Trinkunas

About This Book

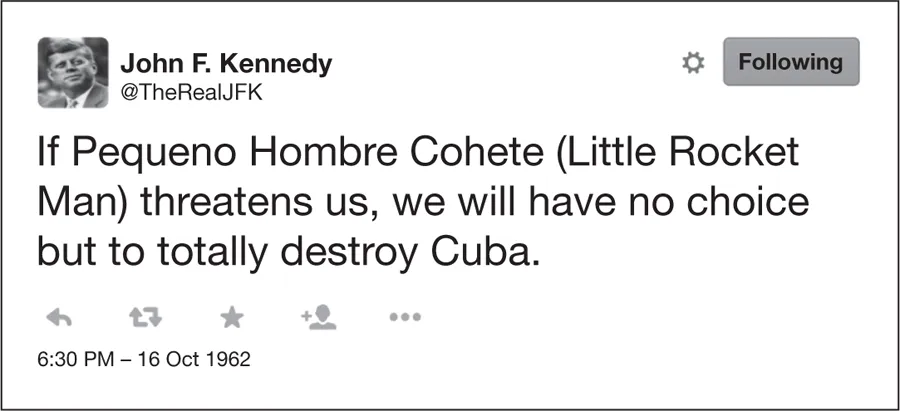

Disinformation and misinformation have always been part of conflict. But as the essays in this volume outline, the rise of social media and the new global information ecosystem have created conditions for the spread of propaganda like never before—with potentially disastrous results.

In our "post-truth" era of bots, trolls, and intemperate presidential tweets, popular social platforms like Twitter and Facebook provide a growing medium for manipulation of information directed to individuals, institutions, and global leaders. A new type of warfare is being fought online each day, often in 280 characters or fewer. Targeted influence campaigns have been waged in at least forty-eight countries so far. We've entered an age where stability during an international crisis can be deliberately manipulated at greater speed, on a larger scale, and at a lower cost than at any previous time in history.

This volume examines the current reality from a variety of angles, considering how digital misinformation might affect the likelihood of international conflict and how it might influence the perceptions and actions of leaders and their publics before and during a crisis. It sounds the alarm about how social media increases information overload and promotes "fast thinking, " with potentially catastrophic results for nuclear powers.

Frequently asked questions

Information